By Art Merrill | Contributing Editor

At the turn of the 20th century, inventors brought out some interesting permutations in bullets as cartridges made the changeover from black powder to smokeless powders that could suddenly drive bullets twice as fast, and faster. And at the black/smokeless cusp comprising the last few years of the 19th century, there appeared a Johnny-come-lately which might have been more successful had it made the scene 20 years earlier. Instead, the unique design of the Lisle Wire Patch bullet is lost in obscurity.

Lube solutions

Commercial muzzleloader conicals demonstrate three different concepts in holding lube. The one on the right is most like the Lisle bullet for cartridge rifles if you imagine a single large groove wound with a pipe cleaner to hold the lubricant.

Of course, cast lead bullets need lubrication to prevent them from “leading” a bore—that is, leaving behind a smear of lead during their trip to the muzzle. Leading begins to occur when rifle bullet velocities start approaching 1,600fps, more or less, depending on the alloy of the bullet and other factors. Handgun cartridges can lead at much lower velocities for design reasons, but that’s a different discussion. Leading is death on precision (accuracy), and lead deposits can be difficult to remove without abrasives. Because black powder-era barrels were made of softer steels than our modern barrels, target shooters of the day especially avoided abrasive cleaning; besides, black powder target rifles generally produced velocities below the leading threshold.

Black powder conical bullet lubes in muzzleloaders were and are more about keeping fouling soft; this makes loading the subsequent shot easier and helps maintain consistent accuracy. These are pretty much the purposes for lubricating round ball patches, too (yet another different discussion). Black powder cartridges also featured a bullet lubricant, or alternatively a paper patch that surrounded the bullet to prevent the lead of the bullet from contacting the bore.

Because smokeless powders burn very cleanly compared to black, there was no longer a need to keep fouling soft, but lubes are still necessary when shooting lead bullets in order to prevent leading. Of course, bullets with jackets of metal softer than the barrel steel became the solution to and replacement for bullet lubricant in high velocity cartridges, but during the short overlap in smokeless powder’s earliest days and the sunset of black powder, one American inventor saw a direct-approach solution.

Physics & snake oil

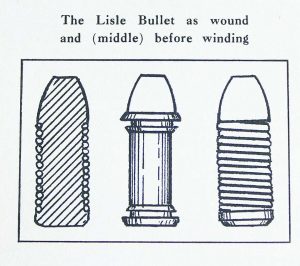

The National Projectile Works on Lyon Street in Grand Rapids, MI, began manufacturing its “lubricated wire patch bullet” in 1897, according to Elmer Lisle, son of the bullet inventor, M.C. Lisle, two years before the US Patent Office awarded Lisle two patents on his bullet in 1899. The Lisle Wire-Patched Bullet approached the leading problem from a “more velocity needs more lubricant” perspective. Rather than a series of two or more circumferential grooves to hold bullet lube, Lisle designed pretty much the entire bullet shank to be a single wide, deep groove. To keep lubricant in place during rapid acceleration upon firing, Lisle wound the groove full of a wire cloth rather like a pipe cleaner. This additional lubricant was apparently at least partially successful in reducing leading at some higher velocities, and so Lisle claimed the design contributed to greater accuracy (no leading) and longer barrel life (no metal jacket or abrasive cleaning). Also note from the diagram that the bullet’s under-bore size shank results in comparatively little bullet-to-bore contact – essentially only where the ogive reaches full diameter, and again at the base – affording less opportunity for leading.

Lisle also claimed the design reduced recoil, which is theoretically possible, because given another lead bullet of the same diameter (caliber) and length, the Lisle bullet is lighter as the wire winding replaces some of the lead. Ike Newton says the lighter the projectile, the lesser the recoil, all other factors being equal. However, a perceived reduction in recoil would be entirely a matter of the shooter’s opinion.

Physics also applies to the maker’s claim of flatter trajectory. Again, assuming all factors being equal; a lighter bullet results in less drop at a given distance than a heavier bullet. Any shooter can prove a flatter trajectory by simply shooting at paper targets, demonstrating theory for himself. So we can’t dismiss all of Lisle’s claims as so much 19th century snake oil.

Winding up

The Lisle wire patch bullet, as diagramed in the February 1942 American Rifleman Magazine.

Early Lisle bullets had a winding of strong cotton or fabric, but such stuff lacked sufficient strength for the job at hand. After some research and development trial and error, the National Projectile Works settled on manufacturing its bullet by first casting the lead in moulds, then rolling them in a machine to ensure roundness and to open the shanks to accept the wire winding. “Patching machines” then wound the bullets with coils of cotton-covered copper or soft steel wire then swaged the bullets to size. In addition to the winding, some of the Lisle bullets also featured an extended copper gas check on the heel that formed a high base. We know gas checks, then as now, reduce leading. Lastly, the bullets received lubricant and subsequent loading into cartridges before packaging.

Four decades later Elmer Lisle would recall, “The .22 cal. wire wound bullets were a revelation because they cleaned the bore after every shot and firing could be maintained indefinitely, but the bullets were too expensive to produce and were discontinued.” Cleans the bore as it shoots? Hmm…Sounds like there might be a bit o’ snake oil in that lubricant after all…

For a time Hensley & Gibbs manufactured their own imitation of the Lisle bullet by first winding coils of copper wire, inserting them into moulds and then pouring in the molten lead. Elmer scoffed at the process saying that his father’s experiments concluded the wire must be wound onto the bullet after casting to achieve best accuracy.

Winding down

Elmer worked at the National Projectile Works from 1901 to 1904; his father left the company in 1906, and owner D.H. Armstrong moved the plant to Napa, CA, where he continued manufacturing the Lisle Wire-Patched Bullet until at least 1911.

“The wire-patched bullets were made in all calibers popular at that time and were in great demand by shooters,” Elmer said in a letter published in the February 1942 American Rifleman magazine. “I am a strong believer in the efficiency of the wire-patched bullet and am sure if they were manufactured again they would quickly be adopted by most shooters due to their great reduction in recoil, flatter trajectory, longer life of barrel and better killing properties.”

Did the wire patch bullet fail to live up to Lisle’s claims, or did it simply succumb to the jacketed bullet that requires no lube at even higher velocities? Did National Projectile Works close its doors due to lack of sales or lack of business acumen? It’s all historically moot, really. While many handloaders today enjoy casting their own bullets, making their own lube recipes and rolling paper jackets, M.C. Lisle’s wire patch bullet is completely forgotten.