by Art Merrill | Contributing Editor

Putting on the pressure

.303 British

SAAMI 49,000psi

.308 Win

SAAMI 62,000psi

.308 CIP 60,191psi

7.62 NATO

NATO EPVAT 60,191psi

SCATP 7.62 60,917psi

SAAMI – Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers Institute

CIP – Commission Internationale Permanente pour l’Epreuve des Armes à Feu Portatives

NATO EPVAT – Electronic Pressure Velocity and Action Time

SCATP 7.62 – Small Caliber Ammunition Test Procedures (US Army)

The different methods of measuring cartridge pressure among these standardizing entities produce slightly different results, but they are similar enough to be confident that loaded pressure differences alone isn’t enough to cause a serious problem when interchanging .308 Win and 7.62 NATO. However, we must consider undesirable combinations of chamber dimensions and cartridge dimensions – and as in the case of the Ishapore Enfields, firearm design – when substituting cartridges.

As you’ve doubtless experienced, shooters can be an obstinate, opinionated bunch of individuals who like to speak in flat statements. But we start running up against reality when we speak in absolutes like, “They’re exactly the same,” or “You’ll blow up your gun.”

Sometimes those absolutes are the result of confusion, and when we talk about the pressures that cartridges produce, there’s plenty of room for that, especially with the beginner shooter or handloader. In a previous article on the .223 Rem/5.56 NATO [TGM July 2016] we covered who sets standards for cartridge pressures and how their different methods of measuring pressure — direct or indirect piezoelectric, measured at the case mouth or case body, or ignition/bullet velocity compared to reference cartridges — produce different results, even though all report in psi, pounds per square inch (see sidebar).

.308 v 7.62

Those differences among SAAMI, CIP, NATO EPVAT and SCATP pressure measurement methods apply to the .308 Winchester/7.62 NATO as well. Unlike with the .223 Rem/5.56 NATO situation, SAAMI does not caution against shooting commercial .308 Win in 7.62 NATO chambers, though several gun manufacturers do. For handloaders, note that load data manuals don’t distinguish between .308 Win and 7.62 NATO or separate loads for bolt guns from those for semi-automatic rifles.

From its inception and its subsequent adoption by the US military in 1954, the 7.62 NATO is intended for use in firearms utilizing gas operated semiauto and fully automatic firearms. When Winchester concurrently dressed the cartridge in civvies as the .308 Win, that wasn’t necessarily a concern, and so some believe the .308 Win is loaded to a higher pressure for bolt action hunting rifles. This perhaps adds to the confusion, as does the misconception that 7.62 NATO for machine guns is loaded to a pressure higher than for rifles.

Designed for the .303 British cartridge (L), the Enfield rifle is not a great candidate for the 7.62 NATO (R) despite its Indian arsenal chambering.

The 7.62 NATO and .308 Win chambers are not identical, the NATO chamber being longer; different sources report from .005” to .013” more headspace in the NATO chamber because specific chamber size is nominal and will vary somewhat depending on firearm and country (nominal size and slight variations apply to commercial .308 Win chambers, too). NATO and commercial ammunition physical dimensions are also nominal, rather than absolute, and will vary slightly, each within their own set parameters. Though .308 Win and 7.62 NATO are considered interchangeable – and physically, they are — there is a possibility that one could run into problems of difficult extraction, stuck cases or worse when mixing NATO chambers or ammo with .308 Win chambers or ammo.

Is there a significant pressure difference between .308 Win and 7.62 NATO? The only way to know for sure is to measure large samples of both using the same methodology, and apparently no reputable major lab has done so. Independent individuals testing small samples using strain gauges or an Oehler M43 Ballistic Laboratory have no quality oversight or official sanction; it appears from their testing that the two cartridges are generally similar in pressure, or that NATO ammo from different manufacturers and countries can vary from each other by as much as 12,000psi, so that question remains unresolved.

What really seems to matter is the platform in which we are firing these cartridges.

In a bind

Shooters, myself included, have fired .308 Win in milsurp Mausers (the Israelis, for example, converted many 98k Mausers to the NATO cartridge) without a hitch. But I experienced an overpressure problem shooting both cartridges in 7.62 NATO chambers after I bought two of the Ishapore Enfield rifles when they first hit the milsurp market years ago. With both Ishapores I experienced very hard bolt lift and difficult extraction after firing .308 Win; even with milsurp 7.62 NATO ammunition bolt lift was unusually stiff.

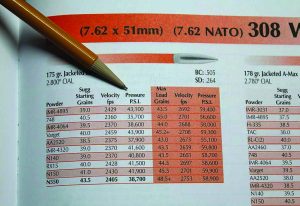

Lyman’s load manual shows starting load pressure for most cartridges. These, for the .308 Win, are below SAAMI’s max 49,000psi for the .303 British cartridge.

This is an example of the error in absolutes. The importers and sellers of these Ishapore Enfields advertised them as being chambered for the .308 Win cartridge. However, neither it nor the 7.62 NATO cartridge offered flawless or even acceptable performance in these two rifles, especially surprising considering these were supposedly combat rifles, the design of which had proved itself reliable for 60 years. What gives?

India manufactured these two particular rifles in 1964 as a stopgap while they acquired modern rifles for the 7.62 NATO round; the British Enfield, first adopted in 1902, was never intended by India for lengthy, front line service. And the receiver was never designed for the pressures of the .308 Win or the 7.62 NATO, both of which exceed the .303 British (for which the Enfield was originally designed) no matter how you want to measure it.

After more testing and research my conclusion is that the pressures produced by the two modern cartridges, combined with the slightly larger NATO chamber, are not a good match for the Enfield’s bolt/receiver design. Unlike the Mausers and other bolt guns with two (or more) locking lugs at the front, the Enfield bolt has a single rear locking lug. Upon firing, the receiver and bolt flex slightly as the expanding gasses keep the bolt pressed backward against its lug at the receiver bridge. The receiver and bolt then relax back to normal position, pressing the bolt hard against the now over-expanded brass case and causing the binding.

How many full power .308 Win/7.62 NATO loads can the Enfield action or bolt lug accommodate before weakening to the point of becoming unsafe to fire? Two thousand? Two hundred thousand? If Ishapore tested and came up with a number before turning out their Enfields, I didn’t find it. But I did find reference to Indian-manufactured 7.62 NATO producing lesser pressure — about that of the .303 British cartridge, which makes sense — than 7.62 NATO from other countries.

Downloading

The safe practice, of course, is to shoot in a firearm only the cartridge that is stamped on the barrel. Agreed, but my Enfield experience shows even that is not an absolute.

From the standpoint of the unacceptable bolt binding and in trusting them to be safe, the Ishapore Enfields are candidates for making reduced loads if we are to find any joy in shooting them. Load manual STARTING loads for jacketed bullets are not necessarily REDUCED loads, but they’re a place for the beginning handloader to go. The Lyman reloading manual has the bonus utility of showing pressures of many starting loads; many .308 Win starting loads fall below 49,000psi (or 45,000 CUP), the SAAMI maximum standard for .303 British.

Reduced loads for cast lead bullets is a good foray into experimentation to download the .308 Win (or other cartridge) after gaining some experience at the loading bench. We shoot cast bullets at lower velocities, and hence lower pressures, than jacketed bullets, but they require a body of handloading knowledge separate from that of jacketed bullets. It’s another genre open to the adventurous handloader.