by Art Merrill | Contributing Editor

Hornady packaging specifies the 7.62x39mm cartridge for their .312” bullets.

Cartridge caliber designations, contrary to common knowledge and the good mental discipline of uniform logic, are not always based on bullet diameters. Keep in mind that bores have rifling and that the rifling is cut or swaged several thousandths of an inch deep into the metal. Though a smooth hole bored through a barrel blank might have an inside diameter of .300”, when you scribe the rifling grooves .004” deep it may then measure .308” across from the bottom of one groove to the bottom of the groove opposite. This is the basis of the .30 caliber 308 Winchester (among many other 30s) possessing bullet diameters of .308”. The bullets are not sized to the bore diameter (.300”), they are sized to the diameter of the groove depths (.308”). The .308 Winchester is so-named for the rifling GROOVE diameter.

But cartridge designations don’t always follow that rule, because nobody agreed on a rule at the beginning of the invention of rifling. The .303 British cartridge bullet diameter is nominally .311”, not .303”. In this example it is .303” from rifling land to land (the bore diameter) but .311” across the grooves. The .303 British is named for the BORE diameter, rather than groove diameter.

Now consider the plinking-popular 7.62x39mm cartridge, with an official bullet diameter of .312” to match the official rifling groove depth of 7.92mm. Commercially manufactured rifles in this caliber may have bores of .310” or even .308”, and factory ammunition bullet diameters may be .308”, .310”, .311” or .312”. If you’ve wondered why the 7.62×39 is not considered an inherently accurate cartridge, mismatching bullet to grove diameter is a good part of the reason why.

Metric inches

The same, but different: The 8mm Mauser on the left has a bullet diameter of .315”; the 8mm Mauser on the right, .323”.

Here’s a good place to mention how we get from millimeters to inches, a fence happily easy to cross. Millimeters, of course, are a metric measurement, whereas “standard” designations are expressed in inches. It’s easy to convert millimeters into inch calibers – simply divide millimeters by 25.4: Xmm÷25.4=X caliber

A common example is the aforementioned 7.62mm – every shooter knows that 7.62 NATO and .308 Winchester share identical outside dimensions and bullet diameters, right?

7.62mm ÷ 25.4 = .30 caliber

7.62 divided by 25.4 equals .300 inches, or .30 caliber bore dimension. Rifling groove depth is, ostensibly, another .008”, giving us .308” diameter .30 caliber bullets. Because Winchester developed the cartridge the company attached its name to it, and we have the .308 Winchester. (Working in the other direction, of course, we convert inches to millimeters by multiplying the two.)

Now, how about 5.56 NATO and .223 Remington? 5.56mm ÷ 25.4 = .218 caliber

.218 inch? What’s up with that? Again, it’s bore diameter. But let’s muddy those waters by noting that 5.56/.223 nominal land (bore) diameter is actually .219”, and bullet diameter .224”, though bullets vary slightly from maker to maker (about .2239” to .2246”, more or less). So, depending upon your chosen system of reference, the .223 Remington might just as reasonably have been called the 218 Remington, 219 Remington or 224 Remington.

Capitalism light

Manufacturers often confuse matters even more for strictly capitalist reasons, the 6mm Remington/.244 Remington being a fine example. Remington first released the .244 Remington cartridge in 1955 with a .2435” bullet diameter. In 1963 Remington renamed the cartridge the 6mm Remington, with the exact same bullet diameter and exact same case dimensions. The difference was in the 6mm rifles having a faster twist to stabilize heavier bullets because hunters were trying to use the cartridge with its light, varmint-weight bullets to take deer-size game. The light bullets weren’t doing the job, hunters badmouthed the cartridge, and Remington responded by making rifles with faster twists, loading factory ammo with heavier bullets and giving the setup a whole new name. And note that the designation is for bore, not groove diameter (6mm ÷ 25.4 = 0.236” and add .004” for groove depth to make groove-to-groove diameter of .244”).

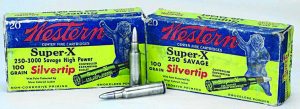

The .250-3000 Savage is a 1915 marketing name that combines bore diameter with advertised muzzle velocity attained with, originally, a too-light-for-deer 87-gr. bullet. Factory loaded with slower 100-gr. bullets, today we call it the 250 Savage.

The name game

There’s way more to cartridge designations than bore and groove diameter. Cartridge designations typically include some “and/or” combination of:

Bullet diameter

Bore diameter

Groove diameter

Bullet weight

Bullet velocity

Case length

Powder charge weight (among black powder cartridges)

Marketing name

Company name

Name of the inventor

Name given by the inventor

Firearm’s name

Government designation

Country of origin or adoption

Parent case, when a conversion

There are probably a few more I missed, too. And sometimes cartridges pick up colloquial names because their original designations seem a mouthful, hence we know the 11.15x58Rmm as the 43 Spanish.

Who’s yer daddy?

There are plenty of cartridges that have “parent” cases – that is, they are an existing case necked up or down to take bullets of larger or smaller diameter than the original loading. Many of these acquire all-new names; for example, some cartridges based on the .308 Winchester case include the .243 Winchester, .260 Remington and 6.5 Creedmoor. Sometimes a bit of the parent case remains in the name of the new cartridge, such as with the .25-06 Remington, the .30-06 necked down to take a .25 caliber (more precisely, .257”) bullet, and the 6.5×284 Norma, based on the .284 Winchester case. In that last example, notice the 6.5×284 Norma combines a metric bore designation, 6.5mm, with the .284 inch designation of the .284 Winchester cartridge’s bullet diameter.

Suffixes & reversals

Different, but the same: Soon after 100-gr. bullets replaced the original 87-gr. bullet in factory loads, the .250-3000 Savage became the 250 Savage because the heavier bullets could not safely achieve 3000fps.

Continental European cartridges typically utilize the metric system of measurement to identify a cartridge by bore diameter and cartridge case length (6.5x55mm). A letter suffix offers additional information such as identifying a rimmed case (10.2x76R). Other letter suffixes may contain vital safety information (8x57J, as opposed to 8x57JS, see below), while still others may denote specific firearms for which the cartridge was originally intended (9x56mm M-S for “Mannlicher-Schoenauer”). Note also that metric designations may or may not include “mm” after the case length. And some unusual-sounding metric cartridges may be common American red-white-and-blues (the 11.25mm Pist. Patr. 632 is our 45 ACP).

Sometimes changes to existing cartridges can also be particularly confabulating, as with the 8mm Mauser, about which I have erred in past reporting, as have so many. When Germany first produced the 7.9x57mm cartridge for its Army in 1888, nominal bore diameter was .311” with rifling measuring .3208” across the grooves, and utilized a bullet of a nominal .319” (that said, I have period military cartridges factory loaded with .3155” bullets). By 1905 the cartridge had evolved into utilizing a .323” bullet (8.2mm) with a corresponding groove diameter. The latter can still chamber in a rifle with a bore of the former, smaller size; obviously, firing the larger bullet through the smaller barrel in an antique rifle is not conducive to a long and happy life. Both cartridges are called the 8mm Mauser; the earlier incarnation is more properly called the 8x57mmJ, the later the 8x57mmJS – and 8mm S Mauser, 8x57mmJS Mauser, and 7.92x57mmJS Mauser – with only that letter “S” suffix identifying it as the later cartridge with the larger diameter bullet.

Americans and British both measure bullets and bores in inches, sometimes naming cartridges to the closest hundredth (45 ACP), and sometimes to the thousandth (455 Webley). Many American blackpowder cartridges logically acquired simple monikers identifying bullet diameter, powder charge weight in grains and bullet weight in grains (45-70-500). Both countries have used case length in inches, as well (500 Nitro Express 3 ¼” and Sharps 50-2 ½”).

Are we comfortable that cartridge designations universally put the bullet or bore diameter first? Don’t get too comfy: the obsolete .577-450 Martini-Henry reverses the practice, designating the parent cartridge bore first. The parent cartridge case is the British military .577 Snider (.577 bore/.585 bullet), necked down to take a .469” diameter bullet (.450 bore). So there’s actually nothing physically .577 at all about the .577-450 Martini-Henry (“Martini” for the action designer and “Henry” for the rifling inventor, by the way). Compare to the 30-338 Magnum, which is a 338 Winchester Magnum case necked down to .308,” a wildcat now marketed as the 300 Winchester Magnum. Or the 7x57mm Mauser, which is a necked-down 8x57mm Mauser.

Though not uniform across the board, cartridge designations do make sense when taken on an individual basis. However, their designations don’t always accurately reflect reality, and so they teach us to never make assumptions.