by Art Merrill | Contributing Editor

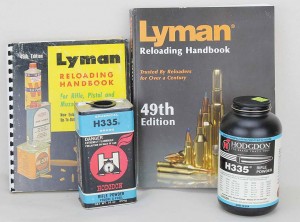

Comparing modern H335 and current load data with older versions of each, there is a half-grain difference in .223 Remington 40-grain and 52-grain bullet starting loads—and the maximum charges differ, too. A half-grain isn’t much difference in bigger cartridge cases, but in smaller cases like the .223, it represents a larger percentage of the total charge and can exceed safe pressure limits to a greater degree than in a larger case.

So, you found a killer deal on some old smokeless powder at a gun show. Or maybe you inherited a few pounds or a friend gave you a container of discontinued powder. Great! But how do you know the old stuff is any good? Could it be dangerous?

Stored away from heat, out of direct sunlight in a relatively cool and, of course, dry place, smokeless powders in unopened containers can last darn near a lifetime. Or more! As an example, today we still find perfectly shootable milsurp ammunition manufactured during or just after WWII.

But, as you discover as you get older, a lifetime isn’t forever, and neither are smokeless powders. Just like people, with proper care smokeless powders can be useful, viable octogenarians—or they can expire prematurely. And just like people, we’re happier when we learn to stay away from the bad ones.

Sniff check

Gunpowder, today called “black powder,” is a mechanical mixture of mostly charcoal with some potassium nitrate (historically derived from bat droppings) and a dash of sulfur. Smokeless powder is as far removed from gunpowder as the mini-gun is from the matchlock; we covered some of its complex chemistry in a previous article. Lacking any sophisticated, technical chemical testing methods, handloaders can still detect deterioration in smokeless powders with our Paleolithic sensors of smell, sight and touch.

When the nitrocellulose in smokeless powders deteriorates, it releases the manufacturing solvent acetic acid—yes, the same acetic acid found in common household vinegar. When that occurs you can detect sufficiently advanced deterioration with the scientifically unquantifiable but logical “sniff check.” If it has a sour smell like vinegar, your powder’s gone bad.

Powder disposal

Some suggest that one can dispose of gunpowder by spreading it in the garden as fertilizer. That might have been acceptable with old-time “black powder,” a mixture of charcoal, sulphur and potassium nitrate, but smokeless powders contain a laundry list of solvents, unsavory chemicals and compounds that should not go into the environment.

In general, the safe method for pulling the latent teeth from smokeless powders is the simple expedient of filling a partial container of powder with water to negate the powder’s flammable nature (smokeless powders are not classified as explosives, they are flammable propellants). But rather than tossing it into the landfill or down the toilet, be sure to check your local regulations regarding further disposal, as a smokeless powder’s chemistry likely makes it a hazardous material requiring special HAZMAT handling and disposal.

A visual sign of powder that’s headed south is in its color. When individual powder kernels take on a lighter, reddish hue, or if you find what appears to be rust colored dust in the container, it’s time to toss it out.

Lastly and perhaps a bit more imperative is the apparent temperature of a powder. Sometimes the deterioration process releases heat (often accompanied by that vinegar smell), and we know what happens when heat is applied to smokeless powders. While the potential for self-ignition is pretty much a concern confined to large quantities of deteriorating powder, if your container of powder feels unnaturally warm to the touch, that’s your sign to deep-six it.

Again like people, powders (and old ammunition) sidling toward the Pearly Gates can become cantankerous and irascible, qualities we can detect with a chronograph. According to Chris Hodgdon at Hodgdon Powder Company (which also markets IMR and Winchester smokeless powders) there is some possibility of deteriorated powders creating excessive, above-load-data pressures, but the greater likelihood is that bullet velocities may become erratic because of the non-uniform burning of deteriorating powder. So if you’re scratching your head over your great handload that’s gone squirrely with large standard deviations and extreme spreads in velocity after loading older versions of the same powder, there’s your clue.

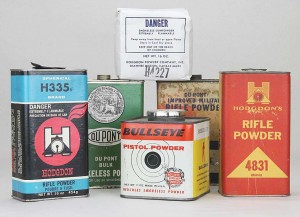

Old powder, old books

And, going the other way, loading fresh, new powders using decades-old load data isn’t a good idea, either. “With newer powders I would not reload with outdated data,” Chris said, “that’s just asking for trouble. Components have changed drastically over the years—such as case thickness, hotter primers, bullets with longer bearing surfaces—and powder technology chemical compositions are completely different today. Load data has evolved with the changes in these components.”

The longevity of properly stored powders lends the same longevity to old loading manuals, so keep those old books. For example, last year a friend gave me a pound of unopened H4227 he picked up at a gun show. Hodgdon discontinued the powder some years ago and it has disappeared from current loading manuals. But a quick scan through equally outdated load manuals on my bookshelf turned up H4227 loads for the .41 Magnum and .44 Special. Its lack of popularity, due to its limited usefulness, is probably responsible for the powder’s demise.

Ninja experiments

While on the subject, be aware that there is also a similar DuPont powder, IMR 4227, still in production and useful in magnum pistol cartridges and the smallest .22 caliber rifle cartridges (.22 Hornet, .221 Fireball etc.). The two powders are not the same and load data is not interchangeable between them. When researching load data online, I found a forum thread wherein someone opined that the similarity between IMR4227 and H4227 is “close enough,” and he suggested using IMR4227 load data for H4227 and to simply reduce starting charges “a grain or two.”

While some handloaders do dabble in such experiments (which might be compared to donning a black ninja suit and playing in the highway at night), it’s not recommended for anyone who likes their firearms and who is intent on retaining functional eyes, noses and fingers for future Paleolithic powder checks. It also points up the imprudence of following the advice of anonymous forum posters. The much more acceptable risk I run in using old published data for the still-good but discontinued H4227 is that I may discover that breathtaking, magical one-hole handload and then run out of a powder I can’t get anymore. So, I might as well load some discontinued bullets, too…

Our conclusion then is that old and even discontinued powders may still be viable, and we have a subjective method for checking them. Passing the see/smell/touch test, we will use data comprehensive to the powder for making safe loads, and we will start by chronographing minimum loads from the manual. That should keep us out of trouble.