By Art Merrill | Contributing Editor

Sitting here, I count off the top of my head at least eight 30-06 rifles in my fearful arsenal, and if gallon plastic bags filled with fired brass is the only measure, then 30-06 is, indeed, my favorite cartridge.

Why 30-06? Maybe you can think of more reasons than I to choose the 30-06, but you won’t come up with any convincing reason for me to give it up. The 30-06 works and continues to work well more than a hundred years after it hit the streets. Though the 303 British and 6.5×55 Swedish cartridges enjoy a few more years of hunting elsewhere, no other homegrown centerfire cartridge approaches the 30-06 in being so popular for so long. There’s got to be a reason.

Ubiquity & recoil

The 303 British (center) and 6.5×55 (L) is to Commonwealth countries and Sweden, respectively, what the 30-06 (R) is to America. Both predate the 30-06 by only a few years.

Factory ammo is ubiquitous, not just in the USA, but apparently is available all over the planet where people hunt. Brass, bullets and dies for reloading are so common as to be remarkable in their absence in any gun shop, which also assuredly has a few so-chambered new or used rifles in the racks.

Recoil from the 30-06 is not particularly heavy, but recoil is really a function of both the cartridge and the rifle design together, as well as how sensitive the shooter may be to being knocked about. Stocks can be deliberately designed to minimize perceived recoil, such as making the front of the comb slightly lower than the rear. Recoil pads are always an option, and today there are pads that direct recoil outward, away from the shooter’s cheek.

Sure, recoil can be a factor in competitions (especially with unaltered vintage military rifles) that require 30 to 60 rounds in a day, and it can be unpleasant even when sighting-in from the bench, but few hunters notice recoil in the excitement of firing at game. Granted, 30-06 recoil, especially with heavy bullets on top of stout loads, can rattle your teeth in a wispy, plastic-stocked rifle. But everyone has their own “recoil limit,” and it’s up to the rifleman to know his or her own and to choose cartridges and rifles accordingly.

Bullet bonanza

The 30-06 (R) is still the standard American reference cartridge, though its offspring, the 308 Win (L), may eventually take that job.

Big bullets for big game and little bullets for little critters is the general rule, and bullet weights for .30 caliber rifles start at 57 grains. Hornady, for one, makes an 86-gr.308” bullet for the 30 Mauser I used to load for my Broomhandle pistol and for plinking in a 30-30. However, given their short length to diameter, they are ballistically pretty much flying pills suitable only for practice or simple entertainment, not varminting over any distance.

Frankly, in a world of so many choices no .30 caliber is a primo small-varmint round anyway. Bullets between 150 and 169 grains are probably optimum in the 30-06 for deer, offering the best of velocity, trajectory and terminal performance tradeoffs in that size game. The 180-gr. bullet is a good all-arounder if we include bigger game like elk. For more confidence in going-away shots there are 200-gr spitzer-type bullets. The 220gr heavyweight bullets are usually reserved for the biggest animals at comparatively close range. To get this maximum weight into a .308” diameter, these heaviest bullets are often round nose (RN) in design, trading aerodynamic performance for high sectional densities that help assure the deepest penetration in tough game.

The 30-06 is still a competition round. I’ve known one Long Range (1,000 yard) competition High Master who chambered his exotic “tube gun” in 30-06, and the Civilian Marksmanship Program games prominently feature original 30-06 M1 Garand and Springfield rifles (to which we can credit most of my bags o’ empties). For target work, Sierra match grade bullets are available across the 150-gr. to 220-gr. weight spectrum, and Hornady’s 168-gr. A-MAX bullets work well in competition at 600 yards in my M1903A4 WWII sniper rifle.

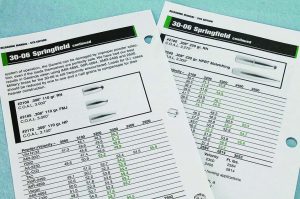

Take a powder

In your chosen load data manual turn to the section that lists powders in their general order of burn rate, and you’ll find the 30-06 uses those considered medium-fast to medium-slow. Powder applications don’t suddenly stop and end with one cartridge; there’s always some overlap between cartridges because the general rule, of course, is to use comparatively faster powders for light bullets and slower powders for heavier in any particular cartridge. In the 30-06 we find data for powders as fast as Vihta Vuori N110 for the 57-gr. Lapua bullet (which, despite my previous comment, has the potential at 3,527 fps to make a decent varmint cartridge if you don’t mind the recoil), to Hodgdon’s slow-ish H1000 for 220-gr. bullets. Three IMR powders, IMR 4064, IMR 4895 and IMR 4350, show up in 30-06 load data encompassing every Sierra .308” bullet from 110-gr. to 220-gr., a statement to the exceptional versatility of these IMR powders. If minimalism is your goal, one of these IMR powders and the 30-06 with the proper bullet may arguably handle every hunting application in North America (but who wants only one rifle?).

30-06 v 308

Sierra data lists bullets from 110-gr. to 220-gr. for the 30-06.

Comparisons between the 30-06 and 308 Winchester are inevitable. The latter cartridge is the result of Army Ordnance experiments to get 30-06 (or more correctly, military M2 Ball) performance from a shorter cartridge, and they pretty much achieved that by lopping a half-inch off the 30-06 case and stuffing it with a then-new ball powder. The 308 Win keeps up with the 30-06 until we get into the heavier bullets. Again consulting the Sierra manual, with 150-gr. bullets max loads between the two cartridges differ by only about 100 fps, but with 200-gr. bullets that split widens to about 350 fps, both velocities favoring the 30-06, of course. Stepping up to tough-n-scary game 220-gr. bullets, Sierra lists no loads at all for the 308 Win and more than a dozen for the 30-06. The 308 Win case simply has no room to deep-seat the long 220 grainers.

In an ideal world of standing broadside shots into the vitals, anything from pig to elk at reasonable hunting distance probably isn’t going to notice any difference between the two cartridges. The 30-06, however, offers a real-world advantage of bullet velocity and penetration at any other angle and over a slightly longer distance, as well as the 220 gr. bullet choice capability.

Geezer guns

IMR 4064 and IMR 4895 work with all Sierra bullets and in the M1 Garand. IMR 4831 usually performs better with the heaviest hunting bullets in non-gas guns.

With a huge variety in factory loaded 30-06 available on store shelves, why should we bother to handload? All the usual reasons apply: lesser cost, reduced recoil loads, practice, the joy of plinking, customizing ammo to a specific rifle for optimum precision, the knowledge derived from experimenting and the satisfaction of DIY. Another of our usuals also applies: old guns.

How old is “old?” Commercial US ammo makers make ammo to Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturing Institute (SAAMI) pressure specifications; load data makers make data not exceeding those maximum specs, and commercial rifle makers make rifles to handle those pressures. For the 30-06, that maximum pressure is 62,000psi. As SAAMI has been around since 1926, we can be fairly confident that rifles factory chambered in 30-06 since about that time are safe to fire factory cartridges. Bolt action military rifles like the M1903 Springfield and the M1917 “Enfield” are demonstrably safe, as well (with the exception of the infamous few “low-numbered” M1903s). Commercial guns predating 1927? Maybe yes, and maybe no!

Though commercial 30-06 cartridge pressures typically fall well short of SAAMI’s allowed 62,000psi, they technically COULD produce such high pressures, and which ones do or don’t is not indicated on factory boxes. The exception is 30-06 loaded to about 50,000psi specifically for the M1 Garand’s gas system, but these feature FMJ bullets unsuitable for hunting. In handloading 30-06, we control the pressures we generate inside the chambers of older guns.

If one single rifle and cartridge could perform all tasks to sterling perfection, there’d be only one rifle and cartridge. Happily, that rifle and cartridge doesn’t exist, so we get lots of rifles and cartridges with which to play and experiment. But for universal availability and across-the-board versatility, it’s tough to beat the 30-06.