By Michael A. Black | Contributing Editor

My first experience learning to shoot a pistol was at Fort Gordon, Georgia in US Army MP school.

At that time the issued weapon was a Colt .45 1911 Government Model. Between the drill sergeants yelling and a bit of practice and luck, I managed to qualify with that pistol, ending up with an expert’s medal.

We were basically taught to hold the weapon with arms extended and to stagger our feet in the same manner as we had during our basic rifle training. A few years later, when I went to the police academy, the range instructors told us the preferred method was the isosceles triangle stance, although some of the old timers extolled the virtues of the Camp Perry style.

With the isosceles, you form a triangle with your feet shoulder width apart forming a straight baseline, and your arms extended, forming the apex of an imaginary triangle. The pistol is held with your arms extended, elbows locked. It was recommended that you bend your knees and crouch slightly as you lean forward. I managed to qualify using that stance too.

After numerous years of doing our quartet of yearly range qualifications, I’d adapted to the isosceles fairly well; then I went through SWAT training and the prescribed method changed to the Weaver Stance.

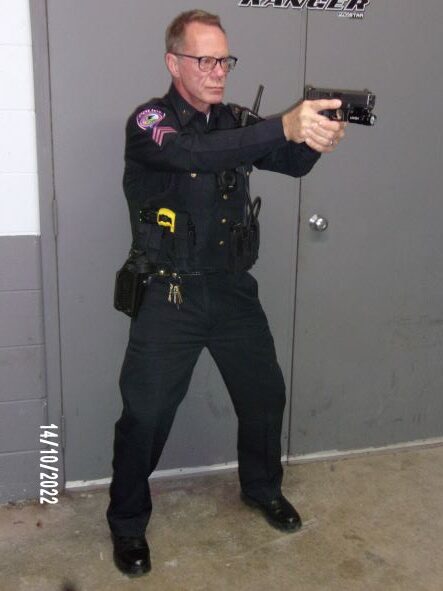

This stance was different from the isosceles, which basically had you doing a full-frontal exposure toward your potential adversary. This is fine when you’re on the range facing paper targets, but in a real life shooting situation the Weaver seemed much more natural. Having spent a good deal of time studying the martial arts and boxing, I found the Weaver much more preferable. For one thing, with the Weaver you’re standing at an angle in sort of a boxing stance. Your strong foot is dropped back and your weak side is angled forward.

I had long adapted this stance when I was on the street interviewing or confronting suspects because it kept my weapon side away from them. It was a very comfortable and natural stance for me, due to my boxing background, and it kept my left hand free to push and offender back while my right hand could either punch or draw my sidearm.

Should you have to draw, your strong (or dominant) arm is held straight, while your weak (or non-dominant) arm is bent, with the weak hand bracing and pulling back slightly on the dominant hand assuring a good strong grip. This creates a push-pull tension grip on the firearm which allows the shooter to minimize the recoil and keep the handgun on target. A good, strong grip on your firearm is best, whether you use the thumbs out grip or not. Find the grip that’s best for you, depending on the size of your hands.

A lot of female officers found the thick grip on the Glock pistols too large for their smaller hands. They often would get the grip cut down. The Smith & Wesson M&P line offers grips that can be size-adjusted for different shooters.

The Weaver also allows for quick side-to-side movement should the situation require it. With the isosceles triangle stance, not only are you placing yourself in a rather static position, you’re also in what my old judo instructor would call point-balance. Should the offender or offenders manage to get close enough to push you either forward or backward, you could be easily knocked down or off track. With the Weaver you can move side-to-side as needed. Just remember, for those of you who’ve never boxed, you never want to move straight back.

The Weaver has been modified, as various scenarios may require, to include movement techniques. Being able to shoot on the move is something that requires practice, but remember, safety first. It’s advisable to practice these movement techniques with a blue gun or, if you must use your own weapon, make sure it’s not loaded.

Referring to the principles of gun safety, which admonishes you to treat every gun as a loaded gun, it’s recommended that you double check it before beginning any such practice. If your handgun is a semi-auto, place a slide stopper in the ejection port as well to prevent the gun from going into battery mode. Then practice moving with your gun. In a real-life shooting situation, you may not have the luxury of a totally flat surface, so if possible, do some practicing on uneven ground.

The recommended way to hold your sidearm is with arms bent, holding the gun relatively close to your chest. If you are moving and a threat suddenly presents itself, you merely extend your arms to the standard shooting position and engage. (See accompanying movement photos 1 through 3.)

Walking should be done with smooth steps in what’s known as the “Groucho Marx walk.” Smooth steps that are not over-extending your legs is preferable. Your goal is to move forward at an even, steady pace, and avoiding an up-and-down bouncing gait, being ready to fire if needed. Your goal should be dictated by the situation. If you’re on a building search, you’re constantly moving. If you’re in a dangerous kill zone, it’s best to find the nearest cover and figure out what to do next.

Once you’ve mastered these movement techniques, try doing them on the range. Again, safety first. Make sure of your backdrop and that nobody is downrange. Whether you’re on the job as a police officer, working security, in the military, or only concerned with personal safety with concealed carry, don’t ever shortchange yourself on safety. Now get to the range and practice, practice, practice.