By Dave Workman

Senior Editor

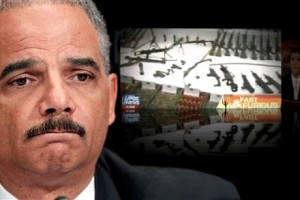

Rather than clear Attorney General Eric Holder of ultimate responsibility for the Operation Fast and Furious debacle, critics of the operation suggest the massive report by the Justice Department’s Inspector General reveals that Holder should have known what was happening, but didn’t.

According to the 512-page report from Inspector General Michael Horowitz, “We found no evidence that Department or ATF staff informed Holder about Operation Fast and Furious prior to 2011.”

That information is contained deep in the document, on Page 299. Subsequent revelations on Page 300 note, “We found that the Offices of the Attorney General and Deputy Attorney General received 11 weekly reports in 2010 from ATF, DOJ’s Criminal Division, and the National Drug Intelligence Center (NDIC) that referred to Operation Fast and Furious by name.”

Congressman Darrell Issa, chairman of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, noted during a hearing with Horowitz as the only witness that the report reveals several people knew about an earlier gun trafficking sting operation’s failures, but they allowed Fast and Furious to move forward “to do the same and more.”

Operation Wide Receiver, launched under the Bush administration, had allowed a few hundred guns to “walk” into Mexico. The same special agent in charge of the Phoenix, AZ field office of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives during Fast and Furious was also in command during Wide Receiver.

Former Phoenix Special Agent in Charge William Newell falls under considerable criticism in the IG report, for “irresponsible” conduct during both Wide Receiver and Fast and Furious.

The IG report also states that, “We concluded that Newell, as SAC, was ultimately responsible for the failures in Operation Wide Receiver…SAC Newell also bore ultimate responsibility for the failures in Operation Fast and Furious, particularly in light of his close involvement with the office’s highest profile and most resource-intensive case.”

Newell reportedly took strong objection to the assertion.

There was considerable blame placed on Deputy Assistant Attorney General Jason Weinstein, who resigned promptly when the report was released. Likewise, Kenneth Melson, who served as acting director of the BATF during Fast and Furious, abruptly announced his retirement.

Yet, what the report does not say but is clearly intimated, according to Holder critics, is that the attorney general should have known about this case. The high volume of firearms involved and the large amount of money that was being paid to cooperating firearms dealers should have gotten someone’s attention early in the investigation, but apparently did not.

That suggests Holder surrounded himself with top-level staff appointees who did not recognize the danger of allowing guns to walk, and didn’t bring it to Holder’s attention, some critics have intimated.

‘Blame Bush’

The IG report opens with a historic narrative of Wide Receiver, which allowed Congressman Elijah Cummings (D-MD), ranking Democrat on the House Oversight Committee, to pointedly remind people that “gun walking” was a strategy used under the Bush administration. Cummings has been aggressive at times in his defense of Holder and the Obama administration by trying to spread the blame for gun walking back to Bush.

While the first three chapters in the Horowitz report place far more emphasis on Wide Receiver and its failures, the document shifts focus to Fast and Furious beginning with Chapter 4.

It details the origin of the operation, and outlines how Newell and his second-in-command, Assistant Special Agent in Charge George Gillett oversaw the investigation.

This section also zeroes in on the involvement of the US Attorney’s office in Phoenix, under the command of Dennis Burke, then US attorney for Arizona. Burke abruptly resigned in August 2011 at the same time that Melson was removed as acting ATF director and transferred to another job with the Justice Department in Washington, D.C.

Burke, an Obama administration appointee, took over as US attorney in September 2009, about six weeks before Fast and Furious was launched. The report said he created two new senior positions and filled them with federal prosecutors Emory Hurley and Patrick Cunningham.

The report criticizes Hurley’s apparent reluctance to bring charges against gun trafficking suspects.

Over the course of the next couple of months, with the cooperation of Phoenix area gun dealers, suspects in the gun trafficking sting purchased scores of guns and spent more than $110,000 at just one gun shop. The report notes how these guns began turning up in various criminal investigations.

It all came to a halt with the December 2010 slaying of Border Patrol agent Brian Terry in the desert mountains about ten miles north of Nogales. Two guns linked to a Fast and Furious suspect were recovered at the scene.

Dealers exonerated

If anyone was exonerated by the IG report, it would be the cooperating gun dealers in Arizona who participated in the investigation. According to the report, this was an “inappropriate use of cooperating FFLs to advance the investigation,” and an entire section of Chapter 7 is devoted to this problem.

This is particularly important to gun rights activists and the firearms industry, because early in the Obama administration, efforts were launched to blame gun-related violence in northern Mexico on lax gun dealers and gun shows in the Southwest.

“The arrangement between ATF and the FFLs in Operation Wide Receiver and Operation Fast and Furious implicated two significant concerns,” the report notes. “First, we believe there is a potential conflict between the ATF’s regulatory and criminal law enforcement functions with respect to FFLs when the ATF seeks their ongoing and extensive assistance in an investigation. Operation Wide Receiver put this tension in stark relief. In that case, the high number of crime-related traces on firearms the FFL sold during the investigation resulted in increased scrutiny of the FFL by ATF’s Industry Operations Division, and the subsequent inspection and warning conference to address unrelated recordkeeping violations strained ATF’s relationship with the FFL.

“Second,” the report continues, “the relationships with the FFLs in these two investigations created at least the appearance that ATF agents approved or encouraged sales of firearms that they knew were unlawful and that they did not intend to seize. In Operation Wide Receiver, agents clearly sanctioned the unlawful sale of firearms; in Operation Fast and Furious, we found that agents emphasized to the cooperating FFLs the value of their cooperation and sought additional cooperation that could be satisfied only by completing sales, at least giving the impression to these FFLs that ATF wanted the sales to continue.”

Rather than engaging in shady business practices, the cooperating dealers were encouraged to complete the suspicious transactions.

“Given that these sales involved illegal straw purchases,” the report states, “we believe ATF agents should have been required to obtain high-level review and approval before seeking the type of cooperation from the FFLs…”

The report notes that the ATF “revised its policies regarding undercover operations and the use of confidential informants in November 2011.” Further, the report acknowledges that “FFLs that voluntarily notify ATF agents about suspicious customers or sales provide critical intelligence about potential firearms trafficking.”

Missing pieces

The IG report acknowledges some missing pieces, and a failure to obtain interviews with some potentially key players. There was also the revelation about the volume of material the IG investigation was given, which raised some eyebrows among Issa and other Oversight Committee members.

“We received over 100,000 pages of documents during the course of our review from the Department, ATF, the DEA, FBI, and DHS that we relied upon in drafting this report,” the IG report says. “These included investigative materials generated in Operations Wide Receiver and Fast and Furious, including documents obtained with grand jury subpoenas, as well as all 14 wiretap applications and other court documents filed in the investigations. We also reviewed thousands of emails from the accounts of current and former senior Department officials and ATF executives and employees, as well as e-mails from other agencies that were relevant to Operation Wide Receiver or Operation Fast and Furious.”

Issa noted with no small irony that if the Justice Department had provided his committee with those documents, which the committee had requested and subpoenaed, the investigation might have concluded months ago.

But the report admits, “We were unable to interview several individuals with information relevant to our review. Charles Higman, the Resident Agent in Charge (RAC) in the ATF Tucson Office during Operation Wide Receiver, had direct management responsibility for the case and made several key decisions regarding how it was conducted. Higman retired from ATF in February 2009 and he did not respond to our repeated attempts to contact him. We also were unable to interview the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agent who was assigned to Operation Fast and Furious on a full time basis and Darren Gil, the former ATF Attaché to Mexico who retired from the agency in December 2010. Both of these individuals declined through counsel our request for a voluntary interview.

“Similarly,” the report added, “Criminal Chief Cunningham, like Burke, declined through counsel our request for a follow-up interview regarding his involvement in the Department’s February 4, 2011, letter to Senator Grassley. We also requested an interview with Kevin O’Reilly, a member of the White House’s National Security Staff, to ask about communications he had in 2010 with former Special Agent in Charge Newell that included information about Operation Fast and Furious. O’Reilly declined our request through his personal counsel.

“We also requested from the White House any communications concerning Operation Fast and Furious during the relevant time period,” the report said, “that were sent to or received from (a) certain ATF employees, including Special Agent in Charge Newell, and (b) certain members of the White House National Security Staff, including Kevin O’Reilly. In response to our request, the White House informed us that the only responsive communications it had with the ATF employees were those between Newell and O’Reilly. The White House indicated that it previously produced those communications to Congress in response to a similar request, and the White House provided us with a copy of those materials. The White House did not produce to us any internal White House communications, noting that ‘the White House is beyond the purview of the Inspector General’s Office, which has jurisdiction over Department of Justice programs and personnel’.”

It is not clear what the next step will be. Horowitz assured Issa’s committee that his office will continue investigating to make sure whistle-blowers have been fairly treated and that no retaliation has occurred.

And ATF sources told TGM that before any firings can occur, there is a process to protect the rights of the people being dismissed.