By Jim Dickson | Contributing editor

Dickson’s Remington Model 241 is a classic in every sense. This little self-loader was a favorite in shooting galleries, and also earned a reputation among small game hunters early in the 20th Century.

John Browning designed his classic semi-automatic .22 rifle in 1913 and Fabrique Nationale in Belgium began producing it the following year.

The most dependable, trouble free and long lived semi-auto .22 ever made, it was a takedown design for easy transport and cleaning. It came apart and reassembled so easily that no one ever had a problem with that chore. Feeding was from a tubular magazine in the butt.

The gun quickly proved so popular that Remington began making it under license as their Model 24 in 1922. In January 1935 Remington’s Crawford C. Loomis led his team in improving the design. Five months later the Model 24 was replaced with the Model 241 which had a wider buttstock and forearm for easier adult use.

The stock was also lengthened on the M241 but I measured them and it was not. The length of pull is exactly the same on the Model 24 and the Model 241. Among the changes was the 19-inch barrel of the Model 24 was lengthened to 24 inches with a tapered barrel which made the gun handle and balance better with greatly improved steadiness for offhand shooting than the FN version or the Model 24.

One of the chief advantages of the M241’s design was its takedown ease for travel or storage.

Overall length was 41 ½ inches and length taken down was 24 inches which made it easy to pack in a suitcase. Remington ads stated it was “A man sized gun that is bigger, heavier, and better than the gun it replaced.”

Designed to handle as responsively as a small gauge shotgun it weighed 6 pounds and was available in both .22 short with 15 round magazine capacity and .22 LR with 10 round capacity. There was a new device that locked the barrel and receiver tight and the internal parts were better finished. Remington discontinued production in 1951 after making 107,345 guns. There has not been a rimfire rifle that was its equal or superior to take its place and its loss to shooters has been greatly mourned.

The specimen pictured here was a .22 short, manufactured in the first part of the second year of production back when the MSRP was a mere $29.95. Of course those were silver dollars back then, not worthless paper script. It takes $700 of that paper money today to buy a new Browning .22.

Barrel markings on Dickson’s rifle are still visible. That’s the original sight, a simple but reliable design.

Since they rarely broke parts and were almost impossible to wear out, they were very popular with shooting galleries and that’s where this one was shipped. The depression was rough on any pay to play entertainment. No one had any money for entertainment when all that many people could afford to live on was beans.

When the local shooting gallery closed down just before World War II it sold its guns and that’s how it became part of my family. Over the years it killed squirrels and rabbits by the score, extremely precise shooting making up for its lack of power. Like a properly loaded Kentucky squirrel rifle, it does not go BANG when fired but instead all you hear is a SNAP that can easily be mistaken for a stick breaking at a distance. This is because the volumetric capacity of the prime and powder gasses is almost reached in the bore before the bullet exits thus producing a silencing effect. A bit longer barrel and you would not hear anything. The design is incredibly accurate. At 20 yards it puts all of its bullets in one ragged hole. Spent cases are its traditional target. The little rifle also shot up every stick in sight floating down the Mississippi river on many days.

Toddlers were taught to wrap around it as best they could while their father held the gun. They were too small to put the stock to the shoulder but as soon as they could point and pull the trigger they got to shoot and hit tin cans at close range with it.

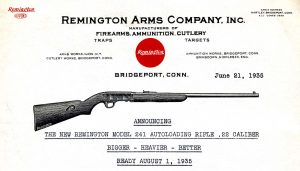

Original factory announcement of the Model 241. (Image courtesy of the Remington Historical Foundation, Inc.)

Back then you raised kids that knew about guns. Loaded guns were around the house but the kids knew they would get a whippin’ if they touched them. Knowing about guns took away the temptation as there was no mystery about them. Good parents also understood that the kids that grew up in the woods hunting and shooting had the best chance of surviving the wars that every generation faces. Overprotective parents who kept “Dangerous things like guns and the outdoors” from their kids did those youngsters no favors. Denying children basic skills like proper handling of firearms and outdoor living constitutes one of the worst and most often fatal forms of child abuse.

The unavailability of ammunition during the war years prevented it being fired much during that period. After the war adults, traumatized by the great depression and the lack of ammo during the war years, bought ammo in quantity for it while kids used their few coins to buy a box or two at a time. No one had any problem selling children ammo in those days. The little rifle just kept working reliably like a sewing machine all through the years without ever needing a gunsmith or any repairs.

Remington knew marketing. This advertisement underscores the Remington Kleenbore line of rimfire ammunition, along with the Model 241 providing something of a backdrop. (Image courtesy of the Remington Historical Foundation, Inc.)

For this test, I acquired a 500 round brick of Remington Golden Bullet .22 shorts. After all those hundreds of thousands of rounds fired through it, the Model 241 still had no trouble putting them all in one ragged hole at 20 yards, which is longer than any shooting gallery I ever saw. Not bad for an 84-year-old shooter that refuses to wear out or break down. It’s still just as much fun as ever to fire.

After the shooting stopped, the little rifle was given a thorough cleaning using Shooters Choice products consisting of their lead remover, copper remover, and FP-10 gun oil. I used one of their brass cleaning rods with a slotted tip for patches and one of their plastic coated stainless steel cleaning rods with brass brushes. Having two cleaning rods instead of constantly changing tips on one just makes life easier.

I would like to thank the Remington Historical Foundation, Inc. for their assistance in providing information and illustrations for this article.