by Art Merrill | Contributing Editor

Alloys and coatings are alternatives to TMJ bullets for reducing airborne lead for indoor shooting. A lack of load data for the Zerillium Alloy™ bullet requires you to put your handloading smarts to work.

[pullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]

Chemistry

So, what’s inside a primer that makes it go “bang?”

From the early 1800s until after WWII primers contained fulminate of mercury; but because of its corrosive effects on metals, comparatively short shelf life and temperature sensitivity, potassium chlorate became a substitute around 1900. But potassium chlorate is still corrosive, and today it is usually found only in milsurp ammunition (hence the advertising notes about “corrosive ammo”).

The most prevalent priming compound now is lead styphnate, developed by Germany in the 1920s. Additives to boost ignition may include TNT, tetrazine, aluminum powder (also used in solid fuel rockets) and oxidizers (including lead compounds). To reduce airborne lead specifically for indoor shooting, some handgun ammunition primers eliminate lead styphnate and instead use diazodinitrophenol (DDNP). Rimfire ammunition cases are relatively weak and rimfire priming ignition can also be weak, so to improve ignition reliability rimfire priming usually contains powdered glass for added friction.

[/pullquote]

Advertising for the world’s very first commercially successful metallic cartridge, Smith & Wesson’s .22 Short rim fire introduced in 1857, promoted the humble round as eminently practical for indoor shooting. And Horace & Daniel didn’t mean indoor shooting ranges, they meant inside your own living room. Perhaps you recall reading that Sherlock Holmes amused himself by shooting a revolver in his London apartment at 221B Baker Street. Interestingly, Dr. Watson never mentioned any complaints from the neighbors…

Indoor shooting has moved from parlors to become full-blown business endeavors, perhaps especially popular in urban areas and where the winters include snow. But indoor shooting presents an additional safety hazard with which we are not concerned when shooting outdoors – lead poisoning from inhalation of airborne bullet lead. Of lesser concern is airborne lead caused by primer ignition (and by lead bullet splatter on the range backstop).

Lead is forever

Think about almost any ailment, from cancer to mental illness, and lead poisoning can cause it. The concern with small doses of lead is that they are pretty much forever because they are accumulative – once it gets into your bones, lead’s half-life is from 30 to 40 years. This means if you inhale, ingest or absorb X amount of lead today, it will take 30-40 years for your body to get rid of half of that amount and another 30-40 years to get rid of half the remaining half, and so on.

The obvious lead poisoning hazard to handloaders is, of course, handling lead bullets. Though not readily absorbed through the thick skin of our hands and fingers, we can absorb the lead on our fingers by touching mucous membranes and thinner skin, and ingest it if we touch lips or food after handling lead. Testing has shown a significant amount of lead in the dust of brass tumbling media, as well. Simple hand washing can prevent ingestion of lead from handling.

Leadless primers?

Most modern primers contain lead styphnate or lead azide. Lead-free diazodininitrophenol (DDNP) primers have been around since at least WWII, but their disadvantages—short storage life and temperature sensitivity—have limited their usefulness. The DDNP primer also requires a larger flash-hole diameter to increase its reliability to ignite powder charges. Despite these problems some makers are providing a limited selection of ammunition specifically for indoor range shooting. If any primer manufacturer is providing DDNP primers for handloading, I’m not aware of it. But if we’re concerned about lead exposure, lead styphnate primers are not where we should be looking first anyway.

Unleaded bullets

A recent article (Shooting Sports USA, October 2014, “Lead poisoning and the shooter,” by Mark Passamanek) reporting testing of airborne lead levels during indoor shooting concluded that lead from lead styphnate primers only contributed about 10% of the lead found in airborne lead. The author estimated that you’d have to shoot 1,000 lead styphnate primers every month for 40 years to get an overexposure.

The bulk of airborne lead comes from the vaporization of lead bullets in their passage down the bore. The article cites a National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health study of 90 people shooting lead bullets in .38 caliber handguns indoors that found 89% of them inhaled airborne lead in excess of permissible OSHA standards.

Slightly longer and taking up more case volume than the 158gr TMJ 9mm bullet on the right, the alloy bullet on the left weighs only 92gr, requiring load experimenting.

According to the study, unjacketed lead bullets produce about 50 times more airborne lead than do TMJ (Total Metal Jacket) and plated bullets that have no exposed lead, and about 20 times more lead than FMJ (Full Metal Jacket) bullets with their exposed lead bases. Clearly, the wisest choice in bullets for indoor shooting are those that have no exposed lead. Or no lead at all. Let’s look at examples of each.

Seeing red

First and most obvious, of course, is to handload with TMJ bullets. This is simplest, as well, because load data for these bullets are common. But as you gain handloading experience and knowledge there are more (and new) options available.

Some years back Smith & Wesson ceased sale of its “NYCLAD” line of loaded pistol ammunition featuring lead bullets with a glossy gray nylon coating. In addition to reducing airborne lead the bullets had a reputation for penetration in the field. Filling the NYCLAD void—at least for handloaders today—AM Precision (makers of Redline Ballistics cast lead bullets) offers lead bullets coated with a red polymer that the maker says results in “no barrel leading at all.” The polymer is impervious to the heat of friction traveling down the bore, so there is no vaporized airborne lead from that source.

The maker says the polymer coated bullets can be pushed to the velocities of similar weight bullets that have metal jackets, and load data for other comparable weight bullets work with these unusual looking red bullets.

The combination of polymer and higher-than-cast-lead velocities promotes such penetration that AM Precision offers two coated hunting bullets for rifles (.45-70 and .30-30), as well as for common indoor shooting calibers such as .40 S&W, 9mm Luger and .380 ACP. Measuring sample bullets for this article showed the coating does not increase their diameters (in fact, the average diameter for the polymer coated .30-30 bullets is .307”—.001” less than the nominal .308”).

The combination of polymer and higher-than-cast-lead velocities promotes such penetration that AM Precision offers two coated hunting bullets for rifles (.45-70 and .30-30), as well as for common indoor shooting calibers such as .40 S&W, 9mm Luger and .380 ACP. Measuring sample bullets for this article showed the coating does not increase their diameters (in fact, the average diameter for the polymer coated .30-30 bullets is .307”—.001” less than the nominal .308”).

“Zeurillium” bullets

Advanced Ballistic Concepts offers a lead-free bullet of a proprietary material the company trademarks as “Zeurillium alloy.” Available loaded in several popular handgun calibers, handloaders can buy the bullets separately; however, because the alloy is about 30% lighter than lead, we can’t use standard published load data. The maker provides a helpful starting point (for 9mm Luger and .45ACP using Hodgdon HP-38) but there are no load data tables yet, leaving load development up to the individual. Of concern to handloaders, to achieve even 70% the weight of a comparable lead bullet, the alloy bullet must be made physically longer. Therefore, to maintain overall length to feed and chamber properly the alloy bullet must seat further into the case; this leaves less case volume for initial gas expansion, which can increase starting pressure and velocity.

Despite their name, Full Metal Jacket bullets (r.) typically have exposed lead bases. The lead cores of Total Metal Jacket bullets (l.) are completely enclosed, preventing hot gasses from vaporizing the lead.

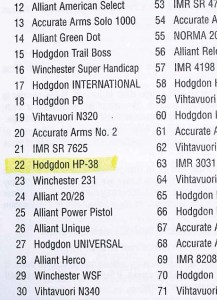

Remember that powder burning rate chart we covered in an earlier article? This is where it comes in handy. Starting with HP-38, we can develop our own loads using the powders adjacent to HP-38 on that chart (such as W-231) as we look for our personal goals of accuracy, velocity or a compromise between them. Obviously, a chronograph is required equipment, as well.

As an aside, the maker says the Zeurillium Alloy™ bullets achieve remarkable penetration, about 26” to 36” in ballistic gelatin. While that is certainly “overpenetration” for some applications, it prompts discussion about unusual possibilities for others—say, pig hunting with 9mm Luger.

Penetration, or a lack of it, results from a combination of several factors, including bullet mass (weight), construction, configuration and velocity. Recoil is affected by bullet weight, too; all other factors being equal, lighter bullets result in less recoil. Such light bullets with loads just powerful enough to cycle semi-auto handgun actions might offer significant advantage for rapid recovery in action pistol sports.

The ultralight Zeurillium Alloy™ bullet presents these and other interesting new experiments for the hand-loader.

Visit the bullet manufacturers’ websites at: mibullet.com and: redlineballistics.com.

[pullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Factory ammo

for indoor shooting

Winchester’s indoor shooting offerings are the Winclean handgun cartridges with enclosed bullet bases and lead-free primers, and Super Clean NT (Non-Toxic) cartridges; the latter includes a couple of rifle cartridges and features soft point, tin core jacketed bullets. Speer Lawman Clean-Fire training ammo (the bullets are non-expanding) eliminates airborne lead with TMJ bullets and lead-free primers. Federal has its own NT line, too, but if you want to reload Speer’s “NT” marked brass, be aware that primers are crimped in, necessitating reaming or swaging the primer pockets, and the .45ACP NT offering has small primers and primer pockets rather than the normal large primer pockets.

A major downside to factory specialty indoor ammo, of course, is the elevated cost, which in the case of the Super Clean ammo runs to about $1 every time you pull the trigger. Handloading cost is dimes on the dollar. Also consider that other heavy metals, such as antimony or barium, often replace the lead in “lead-free” primers and are arguably no more nutritious than lead—and we’ve already seen that lead styphnate primers are apparently insignificant lead sources, anyway.

[/pullquote]