by Art Merrill | Contributing Editor

OK, we were kidding here last month about that electric primer seater, which probably isn’t a viable idea for the home handloader. Yet! But it did raise the question of the need for speed in handloading.

Of course we want to accelerate the handloading process because we are Americans and Bigger/Better/Faster/More is in our national DNA. Labor saving devices are the offspring of that gene. Most schoolchildren learn that Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, often benchmarked as the start of the Industrial Revolution, but fewer know that he also introduced mass production in manufacturing US military flintlock rifles with universally interchangeable parts. That DNA has directed the evolution of handloading metallic cartridges the past 140 years or so, with some major changes occurring after the introduction of electricity.

Our own muscles still power most handloading tools; sensors are also human and include eyesight and subjective “feel,” as when seating primers. But especially when loading large quantities of identical cartridges, electric power is a welcome time and labor-saving option, such as when trimming cases or throwing powder charges. So are cotton gin-ish progressive reloading presses, which are non-electric but exponentially faster than a single stage press.

Options & obsolescence

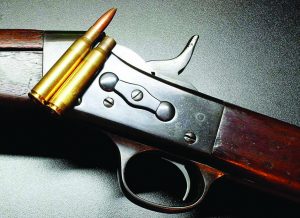

Old rifles and modern factory ammo may or may not be entirely compatible. Case shoulders move forward and expand quite a bit in this 7×57 Rolling Block.

But Bigger/Better/Faster/More eventually reaches a point of diminishing returns. At some point known only to the individual, the cost of tools becomes too prohibitive, or the process too bothersome or complex, and handloading’s appeal finally falls below the KISS threshold of just walking into a gun store and buying factory ammo. However, regardless of the plethora of sometimes-confusing options out there, handloading is really as simple or as complicated as you wish to make it.

For many, myself included, handloading is sometimes simply a money equation. Cost savings over factory ammo is significant when shooting thousands of rounds (and practice rounds) each year in action pistol or 3-gun competition or in regular need of comparatively expensive precision ammo for Highpower and longer range competitions. But more than that, handloading can be an intellectual pursuit, with mass quantity production being of secondary importance.

If you’re interested in old guns that shoot obsolete cartridges, handloading may be your only option because factory loads are long gone. And some old guns chambered and marked for modern cartridges are not always as they appear. For example, there are plenty of 7x57mm Remington Rolling Block rifles still around at shooter prices, but not everyone realizes the 7×57 cartridge of the Rolling Block’s day came out before SAAMI standardizations began, so an old rifle’s chamber may likely be oversized for modern ammo. Because the cartridge headspaces on the shoulder, firing a shorter, modern 7×57 in the Rolling Block’s possibly longer/larger chamber could cause a hazardous situation with the potential for damage and worse.

The simple solution for handloaders, of course, is to move the shoulder forward by fireforming modern 7×57 cases in the Rolling Block with reduced charges. One technique to fireform rifle cartridges is to charge with 10 grains of Unique pistol powder then firmly pack the rest of the case to the bottom of the neck with an inert material (corn meal works) and cap it with ordinary white glue. When fired in the Rolling Block’s chamber, the shoulder blows forward to fit without risking any overpressure. Neck resizing to prevent pushing shoulders back and maintaining low velocities with subsequent 7×57 handloads (you DO have a chronograph, don’t you?) keeps pressures down in deference to the old rifle’s age.

“…do it yourself”

Fireforming without bullets is a safe and easy advanced step for the beginner ready to move forward.

Trusting others to make obsolete ammo for you can be iffy. My single adventure on that path was to pay a “pro” advertising in a magazine to make .310 Greener cartridges for me because I didn’t have a small lathe for thinning case rims; he delivered three months later than agreed and they were of poor quality. Lesson learned: “If you want something done right…” So, in making old guns shoot again you may find yourself seguing into the other genres of handloading—bullet casting and cartridge conversions—each of which requires its own tools and bodies of additional knowledge.

Frankly, I find more satisfaction in load development for obsolete cartridges than in churning out hundreds or thousands of rounds of ammo, perhaps because I’ve never lost my love of learning. Safely loading for esoterics like .256 Newton is not complicated but requires both research and some experience. Back in the 1980s before 7.62x25mm became common with the flood of imported Tokarev pistols, I loaded .30 Mauser (essentially the same cartridge but loaded to lesser pressure) for my C96 Broomhandle pistol in cases converted from another esoteric, the 9mm Magnum. Being both a muzzleloader hunter and a handloader, loading black powder cartridges for an original .45-70 Trapdoor Springfield was a logical step, but also required expanding my knowledge with research. The list goes on.

For this latter pursuit, Bigger/Better/Faster/More has less imperative, and in carefully evaluating the cost-to-benefit ratio of new gizmos we often find there really isn’t anything wrong with the old gizmos so long as we aren’t in a hurry. And there’s entertainment, as well as the educational and nostalgia factors, in discovering and using the handloading gizmos of our grandfathers.

Which some future gun writer may one day say about our own new gizmos. “Can you imagine what it must have been like to seat thousands of primers by hand before the invention of the solar powered digital electronic fully automatic primer seater?” the handloader of 2116 may ask.

Yes, you can!

Too tame, too short: no problem

Safely shooting old rifles is one of handloading’s big benefits. A great many popular cartridges hit gun store shelves before SAAMI, the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturer’s Institute, began standardizing chambers and cartridges in 1926. Any firearm predating SAAMI might have a chamber larger or smaller than “SAAMI specs” and may or may not have the metallurgy or design to withstand repeated firing of modern SAAMI spec pressure ammo.

It works the other way, too. SAAMI often takes old guns into account when setting pressure standards, and so SAAMI spec factory ammo is sometimes loaded to a low pressure. That’s a great safety measure, but it fails to take advantage of modern firearm steels and designs that can withstand higher pressures that equate to maximum cartridge performance. Our 7x57mm is an example.

Introduced in 1892 (the cartridge is aka 7mm Mauser, 7mm Spanish Mauser and .275 Rigby), the SAAMI maximum pressure standard for factory ammo is 51,000 psi (or 46,000 CUP using the old method). Compare that to the similar-size 7mm-08 introduced in 1980, with a max pressure of 61,000psi. The 7×57 is simple to load and components and dies are common, but you must pay close attention to your load data manual when handloading for old rifles. All the 7×57 loads in the Lyman 49th edition load manual are under 46,000 CUP, and it tells you so. Hornady’s fourth edition manual warns against using its load data in Model 1893 and 1895 Mausers. Others, like the Sierra 5th edition manual, don’t even address the matter. Here’s a great example of the need for multiple loading manuals for cross referencing.

The 7×57 is one of those cartridges that factories load unnecessarily tame for modern rifles and which might unsafely headspace in 120+ year-old rifles. Advantage: handloaders!