By Mike Nesbitt | Contributing Editor

While hunting, or just in the great outdoors, with a muzzleloader, one of our prime concerns is keeping our powder dry.

Keep water out of a flintlock’s priming with grease on the edges of the pan

This is equally true if we are carrying a traditionally styled rifle or one of the modern in-line types. For this short discussion I’ll be using and referring to the traditionally styles guns, both flintlocks and cap locks, but my recommendations will certainly hold true for the in-lines as well. After all, while many of us are rather new to muzzle-loading, keeping your powder dry is not a new problem.

Usually there is no trouble with keeping the powder dry for the load that is in the gun’s barrel, that’s rather well protected. Even so, a couple of comments about the powder in the loaded gun’s barrel should be made. In my loads, which still use a patched round ball, the bore is basically sealed with the ball and the lubricated patch. That is also true, although to a slightly lesser extent when the bullet ahead of the powder charge is an elongated bullet or perhaps in a sabot. With the protection of the bullet, the powder charges in the barrel are very seldom moistened by water coming from the guns’ muzzle.

A far more common way for the powder in the gun’s barrel to get dampened is from the breech end, usually through the gun’s nipple or from the flintlock’s flash pan. Too often we might think that the cap on the nipple will protect a percussion gun during wet weather. Actually, moisture can and will use capillary action to “climb” up the side of the nipple inside the cap and it can do that completely enough to render the cap inoperable. And it does not require a rainstorm to do that, a thick fog will carry a lot of moisture too. If the hammer is dropped on a cap that is “polluted” by this moisture, it will drive a lot of the “mush” into the nipple and then we’re really out of business until that can all be cleaned.

A good shot with a flintlock in a pouring rain

One way to protect the cap that is on the nipple is to lightly grease the sides of the nipple before putting the cap on. Be sure you don’t put any grease on the top of the nipple, that would find its way into the nipple. Just lightly grease the side of the nipple, with patch lube, and then slide the cap down over it. That is usually good for all day.

Flintlocks have other problems with wet weather but they are certainly not to be counted out. Some of the later styled flint locks, perhaps those styled after the locks made after 1820, had what we call “rain-proof pans.” Those have priming pans that are “free standing” on the side of the lock plate. While carrying a flintlock in the rain, drops of water will run down the side of the barrel into the groove where the barrel goes into the wooden stock. If you look at that groove, it runs right back to the lock and the pan. A rain-proof pan doesn’t let that water go into the priming powder.

With a flintlock, whether it has a rain-proof pan or not, during wet weather, rain or fog, it is wisest to put a small bead of grease, patch lube again, around the top edge of the priming pan so when the frizzen is closed, the pan is sealed by the grease. That is only good for one shot but that one shot is the most important. And if a follow-up shot is needed, the pan shouldn’t need re-greasing because that follow-up shot is usually taken rather quickly.

Those little tricks simply keep the powder in the gun’s barrel dry and ready for a good shot. We might say, that’s how to seal the powder charge in a muzzle-loader from both ends. What is at least equally important is how to carry your powder and keep it dry so the rifle can be reloaded with confidence, should a follow-up shot, or shots, be needed.

While on the trail, keep your powder horn under your coat

Another “primitive” accessory that can be a great aid during wet or bad weather is a “cow’s knee.” This is a leather, often rawhide, cover that goes over the lock of the rifle, shedding any rain that might fall. It is called a “cow’s knee” because they were often made from the skin that covered the cow’s knee which was already “bent” naturally to cover the lock and the wrist of the rifle or fowler. A cow’s knee is not the best answer and if you do use one, you’ll still have to consider all those other things too.

In rainy weather I would often wear a poncho and it was easy to carry the gun cradled in my arm, under the front of the poncho. That works well but it can get awkward for getting into a shooting position.

Usually there are no problems if shooting in a match while the rain is falling. The picture of Bob DeLisle shooting his Northwest gun and hitting a flying clay during a serious rainstorm is a great example. That shot was a good hit too; you can see fragments of the broken clay pigeon in the upper right corner of the picture.

Notice that Bob’s shooting pouch is hanging outside of his jacket but his powder horn is worn underneath that coat. This introduces my next comment about keeping your powder dry. The powder in that powder horn needs to be protected and wearing the horn under your coat or jacket is the easiest and simplest way to do it. Obviously, if you stay dry, your powder will stay dry. Usually I wear or carry my pouch and horn underneath my coat or capote whether I’m out hunting or on a trail-walk in a primitive shooting match.

Percussion caps for the cap-locks and priming powder for the flintlocks also should be carried beneath your outer garments. I commonly carry either caps, in a capper from Cash Manufacturing, or priming powder in a small priming horn on necklaces, so they hang in front of me and, again, under my coat. That keeps the caps for priming powder dry and very handy.

A powder measure is also needed and for this type of use, where an adjustable powder measure shouldn’t be needed, I carry a powder measure made from antler tip on another beaded necklace so that powder measure stays dry too. You can’t accurately measure black powder in a powder measure that is damp or wet, that just won’t work.

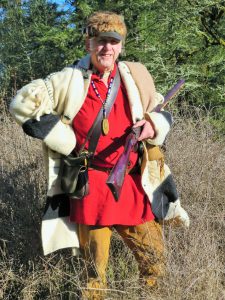

Mike with his priming horn and powder measure, worn under the jacket

While in a shooting match, primitive or otherwise, enough powder for a lot of repeated shots is needed and the best way to carry enough powder is simply with a full powder horn. But on a hunt, particularly for big game, far fewer shots should be needed. So, while hunting, I often carry pre-measured powder charges instead of a powder horn. That simply saves weight and keeps the hunter fresher for another mile…

Using pre-measured powder charges are usually faster than measuring powder from the horn. And on today’s market there are several handy containers made just for carrying pre-measured charges of black powder. I will not refer to any of them during this discussion, mainly because I don’t use them. Frankly, I have no favorites among those accessories so I can’t give any recommendations, although I have used pre-measured powder charges with great success.

When hunting with either one of my .54 caliber rifles or my flintlock .58 caliber Hawken, I commonly carry pre-measured powder charges of 120 grains of GOEX FFg in my mackinaw pockets, maybe five of them. The number of pre-measured powder charges I’d carry was determined by the number of patched bullets I’d be carrying in a loading block, usually five for the .54 but perhaps just three for the .58. That number was simply equal to the number of holes in my loading blocks for those two calibers. And my powder charges were easily carried in empty 35-mm film containers, just pop the top and pour. Yes, that was back in the old days when I used and carried a film camera but I still have several of the plastic film containers.

Keeping your powder dry is not hard to do but always keep things in mind for keeping that powder dry. Being a good hunter is knowing how and where to find the game. After you find that game, these little hints about keeping your powder dry might really help.