By Art Merrill | Handloading Editor

One of the major attractions of handloading is that the per-round cost of ammunition is typically less than that of factory loaded ammunition.

In this regard, handloaders who are avid shooters discover that we don’t really save money so much as we get to put more rounds downrange for the same cost as shooting far fewer rounds of factory ammo. To this end, cast lead bullets cost less than jacketed bullets, and so they afford us even more bangs for the bucks.

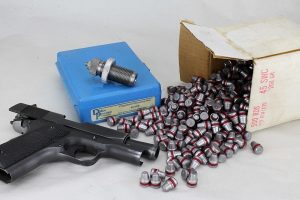

This is perhaps especially true for pistol bullets. Have you noticed that jacketed hollow point (JHP) pistol bullets typically sell in boxes of 100, whereas lead pistol bullets come in boxes of 500, like a shoot-‘em-up brick of .22s? Manufacturing solid lead bullets is way less complicated than manufacturing any other kind of bullet, and that’s reflected in the respective costs.

Hunt, plink, compete

Lead bullets become even cheaper when we cast our own.

The lead semiwadcutter (LSWC) comes closest to a do-everything bullet – and it’s far less expensive than jacketed bullets.

True, bullet casting is a whole different pursuit with its own attendant startup costs, safety considerations and space and equipment requirements, and it’s a good bet that the majority of handloaders will never delve into bullet casting. With so many manufacturers offering cast lead bullets at comparative bargain prices, they don’t need to bother. As a single example, a quick online comparison of .38 caliber 158-grain bullets shows a popular JHP going for 20 cents each per box of 100, compared to a lead semiwadcutter (LSWC) hollow point asking price of only nine cents apiece per box of 500.

Are we going to get the same performance out of both bullets? No, of course not – we must buy bullets appropriate for an intended application and then load them within whatever the limitations of the bullet, cartridge and firearm. While we can utilize lead pistol bullets for some hunting or for self-defense, let’s face it – there are far better choices.

Some applications appropriate to lead bullets include formal bullseye target (aka Precision Pistol) competition as well as action pistol games, small game hunting and plinking. While accomplished pistoleros like Elmer Keith were and are successful in hunting big game with specialized, hardened lead pistol bullets of large caliber, the lead bullets handloaders buy in bulk of 500 are better reserved for varmints and game up to javelina or pigs. Really though, their venues are the plinking field and shooting range.

The full WC

Cowboy Action shooters favor lead round nose (RN) or round nose flat point (RNFP) bullets. Cast bullets in the form of full wadcutter (WC) or semiwadcutter (SWC) type are the overwhelming choice of Bullseye/Precision Pistol shooters, which perhaps says something about how well-made and accurate they can be manufactured or cast at home. The major reason competitors choose the WC or SWC is because their deliberate design is conducive to punching clean, round holes in paper, whereas bullets of other design leave ragged holes that can be difficult to score when they land near a scoring ring, resulting in a competitor possibly losing points.

45 ACP (L) LSWCs feed just fine in many semiautos, and 38 Specials (R) chamber easily in revolvers.

The full WC is essentially a lead cylinder, though several somewhat refined offerings have a vestige of a nose in an attempt at aerodynamic shape. While WC ballistic coefficient (BC) is about on par with that of a parked Winnebago, many handgun hunters believe the WC and SWC outperform RN bullets on dropping game or varmints at short range. Similarly, full WC bullets have been utilized in snub-nose revolvers for self-defense at brass knuckle distance.

The full WC may be seated entirely within the cartridge case with the case mouth crimped over the end of the bullet, which takes up much of the case volume. Unlike with bottleneck rifle cartridges, taking up straight pistol case volume can be a good thing in that it may help keep shot-to-shot pressures more consistent with the comparatively small powder charges we use in pistol cases. On the down side, the BCs of full WCs, as mentioned, are extremely low – into the .035 range – and so velocity falls off as though the WC were launched with the brakes on. So-loaded cartridges present a flat face; lacking any kind of bullet point to help guide them into chambers, reloading a swing-out cylinder is typically slowed by a bit of minor fumbling – even more so with speedloaders. For the same reason, full WC bullets are limited to only a very few specialized semiautomatic pistols that can reliably feed them from a magazine.

SWC: the improved WC

The SWC bullet, however, usually feeds in semi-autos with no modification to the handgun, and is as easy to load into revolver chambers as any RN, FP or JHP bulleted cartridge.

The SWC presents a flat point similar to the FP bullets preferred by handgun hunters and has a better BC than the WC, in the .150 – .250 range. Also, the SWC, like the full WC, punches those lovely clean holes in paper targets, and because they protrude from the case like any other bullet, they can be had in weights heavier than the full WC. The SWC has the advantages of the WC without the WC’s shortcomings.

For these reasons, in addition to its affordability the bulk-purchased, pre-lubricated LSWC may be the most versatile pistol bullets available to handloaders; toss in the comparatively low price of lead bullets, and we can understand its popularity in what may be the most versatile class of cartridges, the .38 Special/.357 Magnum. I also found the LSWC to be an excellent all-around performer in my Model 1911A1 pistol, employing it for target shooting, practice and simple plinking, and for falling plates and bowling pins back when those were the rage – using the same load (5.2 grains of W231 under a 200-grain LSWC) in the same pistol for all those applications.

LSWC bullets also come in hollowpoint versions (L).

Any naked lead bullet presents the problem of leading, the depositing of lead on bores and revolver forcing cones, which occurs when velocities reach a certain point, typically beginning around 900 fps. The specific velocity at which leading occurs varies with the hardness of the specific bullet. In addition to negatively impacting accuracy, leading can raise pressures above normal when subsequently sending jacketed bullets down the bore. Removing leading is a bit of a chore requiring special solvents or a Lewis Lead Remover, and elbow grease. To avoid leading, we accept that we are going to keep lead bullet velocities in check; we might also preclude the problem by utilizing jacketed or clad SWC bullets, which adds to the base price, of course.

Within its parameters, the LSWC is an excellent all-around choice for plinking, practice, smaller game and competition. Returning to our original point, a 500-count box of pre-lubed .38 caliber LSWCs costs about the same as two 50-round boxes of loaded factory .38 Specials. At four grains per load, it takes less than one third of a pound of Unique to load them all; add the cost of 500 Small Pistol primers, and we’re at around $80 for 500 handloaded rounds, about 300 more shots than we’d get for $80 worth of factory loaded ammo.

And that’s pretty attractive.