By Mike Nesbitt | Contributing Editor

Like I said, at least a couple of months ago, I generally reload my straight cased ammo without resizing the brass when those loads are expected to be fired in the very same rifle again.

That’s the way I’ve been doing things for years but even with the excellent experiences that I’ve had with that process, sometimes things seem to need changing. So, a change was made. It was actually necessary but in the long run, it wasn’t for the best.

Let me be more specific. The straight cased cartridges I’m talking about were .50-70s, and I was experiencing some difficulty in chambering the loaded rounds completely. By “completely” I mean they seemed to chamber just fine until the breech needed to be closed. The 1874 Sharps rifles have little or no camming action when the breech is being closed and if a cartridge is not chambered all of the way, the breech block cannot be raised. This is also true if the cartridge has a “high” primer, a primer that is not completely seated into the case. My thoughts about the difficulty in chambering the ammo led me to believe my brass was getting too long and needed trimming.

The way my brass is trimmed is usually with one of the file-trim dies which are produced by several manufacturers. That’s a good way to either check the brass for length or to take a file and trim it to the proper length. I did that and found that most of my cases did get trimmed at least a little bit. But to use the file trim die, the brass must be resized and this exercise left me with a goodly amount or resized cases for the .50-70.

That was fine, I thought, and my “secret plan” was to simply load the resized cases as usual and perhaps continue shooting, along with resizing the cases again for more loading. And to be sure that I had a good supply, the resized and trimmed cases were loaded with well proven loads and made ready.

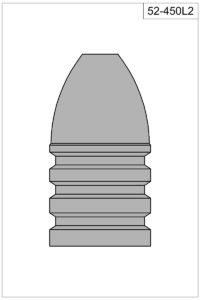

To get specific again, that load used 65 grains of Swiss 1½ Fg powder under a .060” veggie wad, along with a bullet from Accurate Molds’ #52-450L2, a 450-grain bullet very similar to the old government bullet, or #52-460N, also from Accurate Molds but with a flatter nose as well as slightly longer to give it a weigh of 460 grains. Those cast bullets were sized to .512” diameter and lubed with BPC (Black Powder Cartridge) lube from C. Sharps Arms. All of my loads go into Starline cases and for this batch the primers I was using were Federal large pistol caps. Usually, with either of those two bullets, that’s a fine performing load.

Things weren’t going too bad but accuracy was not up to par, not at all. Even so, I kept using that ammunition and kept resizing the brass up to and including the annual .50-70 Match of the Black River Buffalo Runners. That’s an event I look forward to which is held every February and this year’s match left some definite and deep wrinkles in my little brain. It is said that your brain gets a new wrinkle every time you learn something, and I certainly learned things…

The .50-70 Match itself was gorgeous and a lot of fun. This year it was rather lightly attended because of the snow and cold but we got along alright. The wood stove on the range was pumping out heat as well as it could and Tom Brown, the match director, brought his camp stove and made hot coffee for the shooters.

When I said the turnout was rather light, I mean we had only eight shooters. Four of us were shooting Sharps rifles, all Model 1874s by C. Sharps Arms, two other participants shot Remington rolling blocks, one more shooter used a Springfield trapdoor in .50-70, and one “non-conformist” used his C. Sharps Arms Highwall in .38-55. In this match, shooters with rifles in black powder calibers other than .50-70 are certainly welcome to shoot although they are put in a separate category for the awards.

Our shooting is done at 100 and 200 yards with ten shots fired at each distance. And our shooting is done from the sitting position with the heavy barrels of our rifles rested over cross-sticks.

Jerry Mayo is my usual shooting partner for the .50-70 matches as well as for other of our Old West Centerfires matches, we spot targets for each other. When I fired my first shot at 100 yards, Jerry told me where it had hit and I knew it was not going to be a really good day for me.

To shorten this part of the story, as well as my whining, I came in at last place in the match. I’m not trying to say that hasn’t happened before but seems like it had been a long time. My targets showed non-scoring hits at both distances and I commonly get a higher score at 200 yards rather than at 100 yards. Not this time, not at all… My total score in this match was just 139 points out of 200.

My next step was to find out why but in my immediate search, I certainly went in the wrong direction. I cast some bullets, using the #52-450L2 mold, with a harder alloy. Those were loaded with the same loading and taken to the range for some test shooting, off of a benchrest. Only five shots were fired at a 100-yard target. Out of those five shots, only three of them were inside the scoring rings. The five-shot “group” covered the whole target.

That sent me running back to the lead pot, which was emptied and then filled again with a good 25-1 lead to tin alloy and bullets with the same mold were cast until I had a decent supply. Those bullets were sized to .512” again, with the same lube as before, and loaded into un-sized cases.

Yes, I was simply following my own advice from my recommendations of some months ago. And, I went back to my old favorite powder, Olde Eynsford 1 1/2F, still using 65 grains, and still using Federal’s large pistol primers.

Only 16 rounds were loaded, enough to give them a good try. My Sharps rifle was ready and five of those loads were fired at our standard target at 100 yards, shooting from the bench. Those five shots went into a tall 3 ¾” group, in the 7 and 8 rings, to the left of center. That delighted me! For some reason, my shots like to “lean” toward the right when I’m shooting over cross-sticks so having these shots a bit to the left is just fine, for now.

The good grouping of those five shots pleased me quite a bit and they tend to support my idea that my handloads in the .50-70 are more accurate with un-sized cases. The reason for that would most probably be a more consistent exit of the bullet from the mouth of the case. Another way of treating this situation would be to anneal the mouths of the cases and that I have not done with the .50-70 brass. Annealing would soften the brass which would allow the cases to release the bullets more consistently and Starline brass, which I am using, has a reputation for being rather tough.

Annealing might be in my future, perhaps in other calibers such as the .45-90, but for now I’m still pleased with shooting my .50-70 using loads that are prepared with un-sized cases, simply being used in the rifle those cases were fire-formed in.

Another 25 rounds were prepared using the load described above and 20 of those were used very recently in another Old West Centerfires match. The performance of that ammo pleased me quite a bit and my biggest problem in this match was me! I let one shot at 200 yards get away from me, which immediately dropped my score another 10 points below what was possible. But I still brought my score up by about 30 points from what I had gotten in the .50-70 match.

Throwing a shot happens every now and then and, of course, I have more control over my black powder reloads than I have over myself.