By Mike Nesbitt | Contributing Editor

A while ago I bought a Springfield trapdoor, with “1869” on the trapdoor of the action, and finally decided to try shooting it.

When the rifle arrived, it wasn’t in shooting condition. Little things were simply in the way. But now, after giving the rifle some needed attention, I thought about a load worth trying in it, and try it I did.

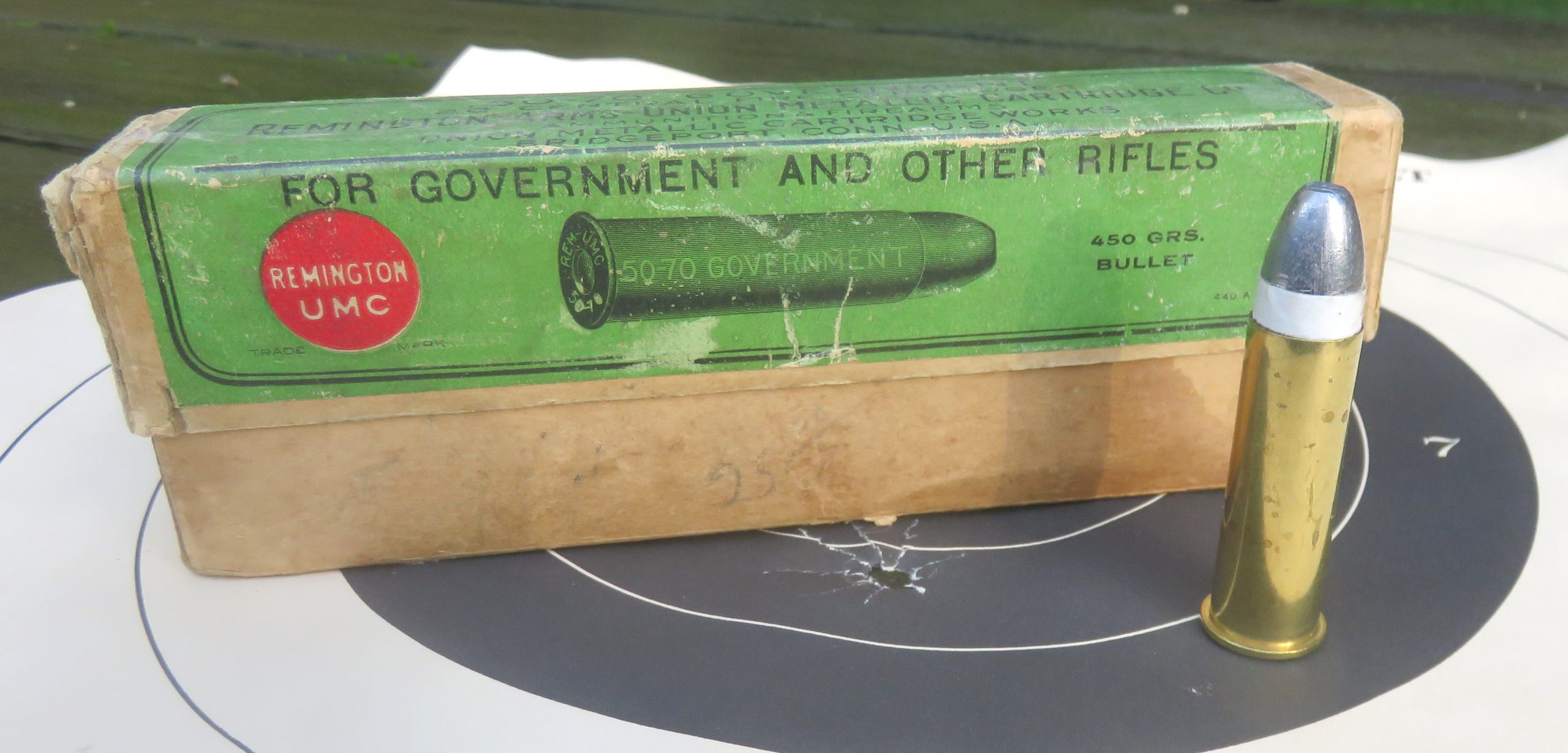

This old Springfield, of course, is in .50-70 caliber, a cartridge with which I’ve done a lot of shooting. Those other .50-70 rifles were either Sharps Model 1874, new rifles by C. Sharps Arms, or the Remington rolling blocks which were re-barreled and re-stocked to follow the lines of the Remington No. 1 Sporting Rifles. The rifle that is my primary subject is not the first trapdoor I’ve fired in .50-70 and it certainly won’t be the last, but there is always some unknown when firing that first shot in any old rifle.

When I got the rifle, it had a broken firing pin. That alone could keep it from being fired. But also, it had a broken ejector spring and part of that spring was extending into the area just ahead of the block. That area needed to be occupied by the rim of the cartridge when the gun was loaded, so, with that broken spring, the block or trapdoor could not be closed when a cartridge was in the chamber. Another spring that was broken was the trapdoor latch spring, called the cam latch spring, that simply needed to be fixed.

It is a lucky thing that all of those parts are easily available. Numrich Gun Parts has them and you can visit their website at www.gunpartscorp.com. Another source is Dixie Gun Works, at www.dixiegunworks.com. Those well-known outfits say their parts are mainly for the .45-70 Springfields, the 1873 and newer models. The three new pieces I just mentioned will fit all of the old trapdoors. And, there is one more source for such pieces which I will mention because they specify parts for the 1868 to 1870 Springfields, for the .50-70s like mine, and they are S&S Firearms with a website at www.ssfirearms.com. Other shops can be found which offer either new or original parts or accessories for these rifles and to find them simply google “Trapdoor Parts” on the internet. That makes them easy to locate.

One reason why I was interested in taking some shots with my rifle, which still wears the full-length stock and even came with the bayonet, was because of my personal admiration for Captain Thomas French, 7th Cavalry. Captain French was a company commander under Major Marcus Reno at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. An outstanding, and perhaps curious, thing about Captain French was that he chose a .50-70 rifle for his personal gun rather than one of the .45-70 carbines that were issued to the other troopers. In the heat of the battle, troopers would get empty fired cases stuck in their carbine’s chambers. They could pass those carbines down the line to Captain French, and French could knock the stuck cases out of those guns with the ramrod from his full-length .50-70 rifle. The carbines at that time did not have ramrods carried inside the butt-stock, those came just a little later. That alone made French’s choice of the .50-70 a good idea.

Also, near the end of the action at the Little Big Horn battle, the Sioux and Cheyenne were falling back and tearing down their camps in order to escape from the area before more “blue coats” arrived. They could be seen from the hills where the troopers were but the .45-70 carbines were not able to send their bullets, with the 55-grain carbine loads, on a “mission” at that distance.

According to Sergeant John Ryan, in his autobiography, Ten Years with Custer, the last guns to fire shots at that battle were Ryan’s scope-sighted Sharps in .45-70 caliber and Captain French’s .50-70, with his rifle’s sight raised for the extended range. History does not give us comments about their effectiveness with those shots but the .50-70 trapdoor was one of the last two rifles to be fired at that famous battle.

My desire to shoot the old rifle I have probably had its greatest roots in simple curiosity. What would it be like to fire the old gun? There’s only one way to find out. With that urging me, some ammo was loaded for shooting the next morning.

The loads which were prepared were made up with certain considerations for the old Springfield. Starline cases were used and I do hope Starline makes another run of the .50-70 cases soon. Those are getting hard to find now. (Let’s all send email notes to Starline at www.starlinebrass.com requesting more .50-70 cases.) I used fired cases and to be sure that the loaded ammo would chamber in the old Springfield, the first step was full-length resizing of the brass. Then the cases were expanded to bell the mouths, then primed with CCI Large Pistol primers. That prepared the cases for loading.

Choice for a powder charge received considerations. To take advantage of a somewhat gentler pressure curve, Swiss 1Fg powder was used. The larger granules of the powder will burn a bit slower than finer grained powder, helping to keep the pressures down. At the same time, those powder granules could keep burning as the bullet traveled down and out of the rifle’s long 32 1/2-inch barrel. Of course, how much powder was also considered. The old factory and military load used 70 grains of powder but I didn’t need that much and I didn’t want that much, at least not for the loads I would use on my first try with this gun. Those considerations prompted me to use just 60 grains of the Swiss 1Fg powder, something like a “carbine load” for the .50-70.

(There actually was a .50 Carbine load that used a 400-grain bullet over 50 grains of black powder but that had a shorter case.)

Selection of a bullet also received considerations. The old Springfield .50-70 rifles were generally fired with bullets of .515” diameter, such as the 425 grain bullets from Lyman’s #515141 bullet mold. I have one of those molds but didn’t want to take the time to cast some bullets with it. Instead, I turned to a paper patched bullet, which was cast with soft lead in a KAL adjustable mold with a diameter of .498”. That sounds terribly small but, of course, that diameter is for the bullet before the paper patch is applied. Also, paper patched bullets are well known for their “bumping up” in diameter while going down the rifle’s barrel. The proper name for this is “obturation,” and it simply means the bullet will get fatter due to acceleration because the back of the bullet accelerates slightly faster than the front of the bullet. In order to help this, these paper patched bullets have a cupped base and the lubricant in the load beneath the bullet will add some hydraulic affects to help the bullets expand.

That obturation should help but on the minus side of my bullet selection was the weight of those bullets. The old Springfield .50-70 rifles had a rate of twist at one turn in 42 inches and bullets weighing 450 grains and less were the most suited for that slow rate of twist. My paper patched bullets were cast to weigh 473 grains, the same as the old Sharps bullet for the .50-70 sporting loads as well as for the .50-90 Sharps. The old “buffalo gun” Sharps rifle’s barrels in .50-70 caliber were often rifled with a one turn in 30-inch rate of twist. So, I must admit that I picked these 473-grain paper patched bullets simply because I had then on hand, already wrapped with the paper patched. They’d be good enough for a first try.

Beneath those paper patched bullets was a “grease cookie” of a secret bullet lube. I call that a “secret” because I can’t actually tell you want it was. This lube is simply a mixture of black powder bullet lubes that I’ve put in a common pan and melted, letting it mix itself as a liquid. Because it has so many ingredients, I can’t actually recommend it and I can’t honestly suggest how to duplicate it. But while shooting, we might find out how well it works.

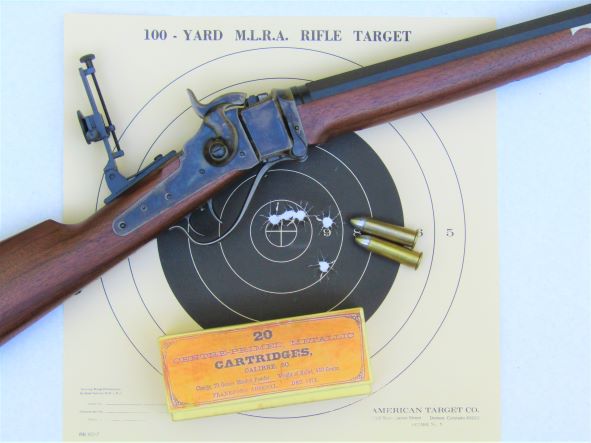

And, while shooting, the lube seemed to work just fine but not everything else. For those shots, targets were posted at just 25 yards and even at that short distance the 473-grain bullets were beginning to keyhole, or punch through the paper somewhat sideways. The long 42-inch rate of twist simply needs a shorter bullet.

Other than accuracy, things were very good and rather pleasant. The old rifle fired and functioned very well. The sights were not “on” for me so my first target showed me where to hold. Then I fired at the 2nd target which is the one you see. The bullet holes in the target are not as “keyholed” as two of them were on the first target which only suggests that the bullets are only trying to keyhole. But the keyholing would happen much more at a longer distance.

So, I’m calling the loads I prepared for this old .50-70 Springfield a complete success, a very successful stepping stone toward some better ammo. The keyholing was no real surprise although I didn’t expect to see it at just 25 yards. My next steps will use either the lighter 425-grain bullets from the Lyman 515141 mold, probably loaded as cast and pan lubed rather than sized to .512”, or some 425-grain paper patched bullets from my adjustable mold. The old commercial sporting load for the .50-70 used a 425-grain paper patched bullet and that was intended for the Springfield rifles as well as other sporting rifles. And I might increase the powder charge but tweaking like that must remain to be seen. A report will very likely follow.

There is just a little more that should be said. First of all, it was a real treat to burn some black powder with this 156-year-old military rifle. And all future loads will also be only with black powder. But before these first shots were fired, the old gun got a complete “physical” when the broken firing pin and broken springs were replaced. It was certainly in good enough condition to be fired. The gun’s barrel isn’t as good as it once was but plenty of rifling can still be seen along with just a couple of pits. Care must be taken when considering whether or not to shoot such a rifle because most of the time we’ll have no hints about the gun’s history or background. In this rifle’s case, it was easily good enough to shoot and now I’ll be even more eager to shoot it again.