By Mike Nesbitt | Contributing Editor

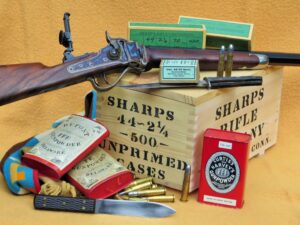

This is my third installment about reloading black powder cartridges, and now we get to talk about some of the bigger stuff.

I’ve put bottleneck cases in a separate class simply because reloading for them can be slightly different from reloading with the straight wall cases. Actually, I’m not saying that it is different but with certain situations it could be. And those situations raise their head often enough to warrant this separate story about them. With those defusing remarks behind us, let’s dive into reloading for the bottleneck cases.

Among the old black powder cartridges there are several with bottleneck shapes. Those will certainly include the .38/56 Winchester as well as the other large .38s made for the lever action repeaters. On the small end, we’ll mention the .40/50 Sharps BN (Bottleneck). Like the .38/56, we should include the .40/65 Winchester and that is a very popular cartridge for single shots today. Where our real focus will begin is with the .40/70 Sharps BN and we’ll remain focused on the .44/77 Sharps and the big .44/90 Sharps. All of the Sharps .44s were bottleneck cartridges.

Bottleneck cartridges were what really set the pace for performance back in the early 1870s. The first matches at Creedmoor, which included targets at 1000 yards, were won with the bottleneck .44s, actually using the standard 2 ¼ -inch case (from the .44/77) but crammed with 90 grains of powder and topped with up to a 520-grain paper patched bullet which just barely entered the mouth of the case. In later years that was catalogued as the .44/90 Regular and those were available, at least on custom order, from Winchester as late as 1916.

Yet even with all of the credits that bottleneck cartridges can receive, they also earned bad remarks starting back in the 1870s. Those bad reviews included how the bottleneck cartridges suffered from increasing recoil, with increased fouling which made the barrels hard to clean, and they were hard to reload. Personally, after shooting bottleneck black powder cartridges for a number of years, I can’t see any particular disadvantage to using them.

Black Powder Cartridge Reloading: Pt. I, Revolver

Before we discuss loads for the bottleneck cartridges mentioned above, I want to introduce a handloading accessory that other black powder handloaders might think I should have mentioned before now, the drop tube. A drop tube, of various lengths, lets the powder fall into the primed cases, gathering more speed than if simply poured from the powder measure or simply through a funnel. That added momentum lets the powder settle much more evenly in the case and it also allows more powder to be put in the case. I certainly have a drop tube but I don’t use it all of the time. While talking about loading a couple of the cartridges that will be mentioned as we continue, a drop tube will be used and it certainly deserves recognition.

Also, while we’re still talking about things in general, I always re-size my cases when loading for a black powder bottleneck cartridge. That’s just my own “rule of thumb” but I find it is easier to maintain consistency, such as while seating the bullets and to keep the loaded cartridge easy to chamber, by re-sizing the brass. We’ll talk more about this in a future installment.

The Big Sharps

We’ll start our specific conversation about reloading with the .40/70 Sharps. (I’d start with the .40/50 Sharps BN if I had one.) The .40/70 is one of the old Sharps cartridges and it was introduced with the Model 1869 rifle. It was a very popular round for hunting medium game and for mid-range (300 to 600 yards) target shooting. Some buffalo were undoubtedly shot with the .40/70 but I consider it to be on the light side for a buffalo gun. The old standard loading used 70 grains of powder under a 330-grain bullet, usually paper patched.

Cases for the .40/70 Sharps bottleneck are not made at this time except by the custom brass makers, such as Roberson Cartridge Company (www.rccbrass.com), who turn the cases on a lathe. Those are very good but on the expensive side. The re-formed brass I use comes from Buffalo Arms Company (www.buffaloarms.com) and they resize new .45/70 cases to neck them down to the .40 caliber, then stretch the cases to the 2 ¼-inch length for the .40/70.

In addition to a 3-die set for the .40/70 Sharps BN, I certainly do recommend a file trim die, or some other method of trimming the brass, because the cases will stretch when firing. For some reason, I’ve noticed this to a greater extent with the .40/70 than I have with other calibers.

My favorite load for the .40/70 Sharps BN uses a 375-grain cast bullet from Accurate Molds’ #41-370D, a flat nosed bullet with three generous lube grooves. For fuel I’ve found that Olde Eynsford 1F powder does just fine, a full 70 grains of it. That powder will fill the case to the top but when poured into the case through a 30-inch drop tube the powder settles almost to the bottom of the neck. A .060” fiber wad is used over the powder, to protect the base of the bullet, and then the bullet is seated over the wad. No other compression of the powder is needed.

Black Powder Cartridge Reloading – Pt. II: Intermediate Rifle Cartridges

And because that bullet has no crimp groove, a taper crimp die is recommended for adding a slight crimp to the load after the bullet is seated.

That load shoots accurately in my Model 1874 rifle by C. Sharps Arms with the Badger barrel which has a 1 in 17” twist. It has given me good groups and for a while I used it as my iron-sighted rifle for silhouette matches where accuracy is needed out to 500 meters. The reason I stopped using that particular rifle was because my eyes favored another gun which is scope mounted, not because of any short-comings of the .40/70 BN cartridge.

The next bottleneck cartridge I’ll focus on is one that I was tempted to start with, the famous .44/77 Sharps, because it is a personal favorite. The .44/77 started life in 1869, being chambered in the Sharps rifle of that year. Its original loading used 70 grains of powder under a 380-grain paper patched bullet, so we might have called it the .44/70 but its official name is the .44-2 ¼” Sharps. The name “.44/77” became its common title after UMC (Union Metallic Cartridge Company) began loading the ammo for it with 77 grains of powder under a 405-grain patched bullet.

My own loads for this cartridge have varied from 400-grain bullets up to 480 grains and possibly higher. I do have molds for heavier bullets and those heavier bullets do perform better at long range, over 600 yards, but for more pleasurable shooting I prefer to use the bullets on the lighter side. My favorite choice is a 405-grain bullet cast from a Steve Brooks mold, dropping from the mold with a .446” diameter with three lube grooves and an “Original Postell” style nose. That bullet is lubed with BPC lube and loaded over 70 grains of Swiss 2Fg powder. An .060” fiber wad is placed over the powder which is only slightly compressed as the bullets are seated. The seating die is adjusted to give the cases just a tiny bit of crimp as the bullets are seated and with that, after being wiped off, the ammo is ready for shooting.

That’s what I like for my .44/77 shooting for fun and that “fun” can easily extend out to 300 yards. While that load is not as heavy or as “packed” as loads with more powder and heavier bullets will be, it still has the “crack” of the .44 Sharps with plenty of punch for targets or medium game. And the powder burns cleanly enough that only a blow tube is used between shots, where three or more breaths blown through the barrel adds enough moisture to keep any fouling soft.

The .44/77 is another cartridge that custom brass needs to be purchased for, or re-formed brass re-shaped from .348 Winchester cases. I was lucky enough to get interested in the .44/77 when Jamison Brass was still in business and I’d like to see someone make new cases for the .44 Sharps cartridges today.

While the .44/77 will reach out to 1,000 yards and even farther, when I’m planning on shooting at those long distances, the rifle I like to use is my good ol’ .44/90. That’s the “big thumper” of my Sharps .44s and the .44/90 is regarded as a heavy recoiling rifle. It was intended for shooting at longer ranges and it was immediately put to good use by the buffalo hunters in Texas, in mid-1872. The original sporting load used a 450-grain paper patched bullet over 90 grains of powder. Bullet weights did vary somewhat, climbing to 520 grains, and the powder charge could be increased, either by the handloader or by order, to 105 grains.

The only real difference between the .44/77 and the .44/90 Sharps is the length of the case and the .44/90 has a case 2 5/8 inches long. Both cases have the same length necks. The longer case, of course, has more powder capacity. The lightest powder charge I’ve used in my .44/90 is 90 grains and I’ve found bad or inconsistent performance with anything less than 90 grains. (This might be another slam against the bottleneck cases, straight cases seem to work much better with reduced loads.) Those 90 grain powder charges can be loaded without a drop tube but for heavier loads, and I’ve used 95 and 100 grain charges, a drop tube will have advantages.

As with the other bottleneck cases already mentioned, the only new brass available for the .44/90 Sharps is from custom makers. Buffalo Arms does offer .44/90 Sharps brass, re-formed from new .50-110 cases. There were also other .44/90 cartridges such as the .44/90 Peabody and the .44/90 Remington Special which were both bottlenecked but with different case lengths and shape.

Lyman discontinued one of the best bullets for the .44/90 long ago and that was their #446187, I’m lucky enough to have one. Other bullets that I will recommend are Accurate Molds’ #44-450B and #44-470N, with weight of 450 grains and 475 grains, respectively.

As with the bottleneck cases previously discussed, the .44/90 usually needs no advance compression of the powder before seating the bullets. That does make the bottlenecks a little easier to load but we can’t actually call that an advantage. And a good load to start with, one that had worked very well for me, uses the 450-grain bullet from the Accurate mold seated over 90 grains of Olde Eynsford 1F powder. That will “boom” loud enough to make heads turn on the firing line and it will perform well enough to make those other shooters look again.

In general, I’ve had no particular problems in shooting or reloading the black powder bottleneck cases. In fact, I could say that I prefer them. The .44/77 is probably my favorite black powder cartridge although my best shooting has been done with the .44/90, providing me with my best number of hits at long range as well as my highest scores on short-range targets. While the straight cased cartridges are more popular today, just like they were in the late 1870s, it looks like I’ll keep on doing most of my shooting with the Sharps style rifles chambered for bottleneck ammo.