by Art Merrill | Contributing Editor

The case on the right used a Boxer primer and is the type we reload. The aluminum case on left used a Berdan primer—note the two flash holes with the anvil between them on the Berdan case.

For the beginning handloader primers are both simple to understand and yet slightly more complex than they first appear. Rifle and pistol primers are the same physical size, so what makes them different? Can we substitute one for the other? What secret ingredient goes into making Match grade primers? Why are Berdan primer cases not reloadable? Let’s look at the last question first.

Boxer v Berdan

Here in the US metallic cartridges use the Boxer primer, patented in 1889 by Englishman Edward Boxer. Oddly enough, the Berdan primer, patented in 1886 by American Hiram Berdan is in universal military use in England and Europe. The significant difference between the two is that the Boxer has an integral anvil within the primer, and the Berdan’s anvil is instead part of the cartridge case. With both, when the firing pin strikes the outside surface of the primer (cup), it crushes the pressure sensitive primer chemical between the cup and the anvil, causing it to ignite. That flame passes through the flash hole(s) into the powder charge.

While we speak of Berdan primed cases as being “not reloadable,” that isn’t true; but decapping Berdan primers requires different tools because the primer pockets of Berdan type cases have two flash holes (with the anvil situated between) instead of the Boxer’s single flash hole. Also, Berdan primers are not commonly available in the US, so as a safety measure manufacturers typically use Berdan priming for aluminum or polymer case ammunition that are not strong enough for repeated reloading and firing. Attempting to decap a Berdan primed case will break your decapping pin. How can you tell if your brass case has a Berdan primer? Shine a light into the empty case; if you see two flash holes it’s a Berdan, if a single flash hole, it’s a Boxer.

Rifle or Pistol

Some handloaders prefer to seat primers with a handheld tool, such as this Lee Precision Ergo Prime. Photo courtesy Lee Precision

Boxer primers come in only two flavors, Rifle and Pistol. Each of these come in two different physical sizes, Large and Small, and specific cartridge cases take one or the other specific size primer. For example, .223 Remington uses Small rifle primers, .30-06 uses Large. The .38 Special takes a Small pistol primer, the .45 ACP a Large. The rule of thumb is that the larger cases generally take Large primers and small cases, Small primers. Yes, there are some specific exceptions among advanced handloaders and precision shooters, but we are concerned with beginning handloading here. Your reloading manual will tell you what size primer to use.

Besides the physical size difference between Large and Small primers, what differentiates Rifle and Pistol primers? Handloaders say that rifle primers are “hard” and pistol primers are “soft.” For our purposes those are general references to firearm firing pins, the assumption being that rifle firing pins strike primers with more gusto than do pistol firing pins, so rifle primers must be “harder” than pistol primers.

We ask a lot of that tiny pill of pressure-sensitive priming compound; it must be sensitive enough to work every time, but not so sensitive that it ignites prematurely during handling or chambering. Manufacturers test their primers using different standards for rifle and pistol primers. They test primer samples by dropping a steel ball onto them from specific heights; of course the higher the height, the greater the striking force of the steel ball. Dropped from below a specified height no primers must detonate; dropped from above that height, all primers must detonate. Those specified heights are higher for rifle primers than for pistol primers, so rifle primers are indeed “harder” than pistol primers.

Three types

[pullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”#40FF00″ class=”” size=””]*In addition to Boxer and Berdan primers there is a third type, the battery cup primer. In 1868 its American inventor, Brigadier General Stephen Vincent Benet, intended it for metallic cartridges, but it found its home with shotguns as the Number 209 shotshell primer. Many modern inline muzzleloaders also take the 209 primer, as it delivers a hotter ignition than do percussion caps. The 209 primer is not used in metallic cartridges, but all-brass shotgun shells do use Boxer primers.[/pullquote]

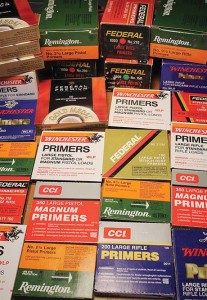

Each size of Rifle or Pistol primer has one of three types of priming: Standard, Magnum or Match. Think of the Standard primer as, well, the standard. Magnum primers differ in providing a hotter, more powerful ignition for larger powder charges in larger magnum cases. Advanced handloaders sometimes “tweak” unsatisfactory loads by substituting Magnum primers for Standard primers, but it takes knowledgeable experience to troubleshoot problems to this point, and the beginner attempting it could get into trouble with too-hot loads. Stick with reloading manual recipes until you’ve gained some experience. That said, we might as well add a little confusion by noting that Winchester splits the difference in making a single primer “for Standard and Magnum loads,” according to the package label.

Match grade primers differ from Standard primers in providing more consistent ignition temperature for more consistent shot-to-shot accuracy. The tighter manufacturing quality control on Match primers means they cost more than Standard primers. You must ensure your own quality control in each step of your handloading process to benefit from Match primers, so if you’re just beginning handloading, save your pennies and stick to Standard or Magnum primers, whichever the load data book calls for.

Priming tools

We install new primers in cases using either hand-held, bench-mounted, or press-mounted primer seating tools.

Hornady, Lee, Lyman and RCBS all make hand-held priming tools that work pretty much the same way: pour your primers into the enclosed primer tray and shake to flip them all anvil side up. Install the proper shell holder, place a case in it and squeeze the handle to seat the primer. Releasing the spring-loaded handle loads the next primer for seating. These tools start at about $20 and escalate to nearly $80 for RCBS models that don’t require separate shell holders.

[pullquote align=”” cite=”” link=”” color=”#40FF00″ class=”” size=””]What makes Rifle primers harder than Pistol primers?

The thickness of the primer’s metal cup.

Small pistol primers:

Dia: .175” Thickness: .0165”

Large pistol:

Dia: .210” Thickness: .0169”

Small rifle:

Dia: .175” Thickness: .0252”

Large rifle:

Dia: .210” Thickness: .0252”

Using Pistol primers in rifle cases can result in pierced primers, blowing gas and particles back toward the shooter. Using Rifle primers in handguns can result in misfires. Also, Large Rifle primers have about 9.5mg more charge than do Large Pistol primers and could create a too-robust ignition in pistol cases. Of course there are specific exceptions to this rule among advanced handloaders, particularly in extreme precision shooting such as Bench Rest competition. Always use the proper primer in the proper case.

[/pullquote]

There are also bench-mounted primer seaters starting at around $100 that work the same way as the primer seater already attached to most single stage “O” frame presses. In fact, the reloading press primer seaters have always worked perfectly for me, nary a glitch in more than 30 years, and I see no reason to spend the extra money for other seaters. You can even buy “automatic” primer feeders for these reloading press seaters for about the cost of most hand-held seaters.

Whatever priming tool you choose, it will offer you both Large and Small size primer seater attachments. The Large size works with both Rifle and Pistol primers, the Small size does likewise.

Fully seated

There is a staggering selection of primers available to handloaders. Changing to a different brand or type (Standard, Magnum or Match) sometimes solves problems with handloads.

Military brass has crimped-in primers. While decapping is not a problem, you will crush and waste new primers during seating unless you first remove that primer pocket crimp with a tool that either cuts or swages it. Cutters may be inexpensive handheld or drill press mounted devices or attachments to case trimmers. RCBS makes a swager that mounts in your press like a reloading die. If you’ve got deeper pockets Dillion offers a beefy bench-mounted swager.

New primers may seat in unswagged military brass pockets, but they may not seat fully unless you remove the crimp. They also may not seat fully in dirty primer pockets. Primer pocket cleaners are even more diverse than swagers, running the gamut from simple wire brushes mounted in screwdriver type handles to electric models.

It is very important to fully seat primers in their pockets, which means the primer cup face is very slightly below the level of the case head. Primers that protrude above the case head can cause revolver cylinders to fail to revolve properly and prevent single-shot actions from closing. In semi-automatic firearms a protruding primer can cause a slam fire or worse, an out-of-battery firing.

In a slam fire the firearm immediately discharges unintentionally when the cartridge has seated in the chamber and the bolt has “slammed” home, the bolt face detonating the primer. An out-of-battery firing occurs when the primer and powder charge ignite before the bolt has fully closed and locked. The cartridge, unsupported by the chamber and unsecured by the unlocked bolt, acts essentially as a small grenade and can destroy a firearm—or a life.

For this reason I discourage handloaders from using handheld priming tools while watching TV or otherwise distracted. Stay focused on your priming task, and check the seating of every primer by standing the primed case on your benchtop—if it rocks slightly the primer is not fully seated. Try seating it again; if that fails then remove the primer and clean the pocket or remove the crimp.

Remove primer pocket crimps from military brass with a swage, such as this press-mounted kit from RCBS, or with a cutter. The Sinclair cutters can be mounted in a handle or chucked in a drill press for high volume work.

In this situation the safest method is to fire the primed, uncharged case in your firearm, if possible, before decapping because there is a slight possibility of igniting a live primer when the decapping pin pushes against the anvil, crushing the priming compound between anvil and cup. I’ve never heard of it actually happening, but the possibility exists.