By R.K. Campbell | Contributing Editor

If there is anything those of us that love the 1911 appreciate, it is a sense of history. Emotional attachment is also important but history is a beckoning call.

I would have been bored long ago with firearms if the technical aspects were the only part of the equation. I think that the collector that stays to himself and dotes on his collection is more of a reality in other pursuits than gun collecting. We like the company of kindred spirits. The men that designed the pistols are immensely interesting and so are the men and women that have used the firearms to save lives. If anyone involved receives far too little admiration it is the craftsmen that manufacture the firearms. Furthermore, the men and women that take the 1911 in hand and win a pistol match are athletes that deserve our respect.

Recently I have been able to examine and fire a link with the past. A well preserved handgun with quite a history at Camp Perry the 1911 is an interesting genre of the 1911. I have often stated that the 1911 is the finest fighting handgun ever made. Hand fit is ideal. The trigger features a straight to the rear compression. The bore axis is low, limiting muzzle flip. The pistol has fight-stopping power. These same attributes make the pistol an excellent target gun. You do not need a lot of power in a target gun, but if the pistol is the service handgun then you were firing the .45ACP a generation or two.

The author is getting the hang of bullseye; it is challenging. It was cold that day but the old 1911 did its part.

With suitable modifications the 1911 is a great all around handgun for one role or the other. Over the years a number of target features have slipped into the 1911. A long trigger and flat mainspring housing are among these, as well as the target trigger. An adjustable trigger has no place on a combat pistol. Target grade 1911 handguns were developed shortly after World War One in order to compete in the National Matches. These matches involved long range fire at small targets.

The Springfield 1903 rifle had been designed for long-range rifle accuracy. The Colt 1911 had not been designed for accuracy and needed considerable work to provide the specified accuracy at a long 50 yards. The heavy trigger and small sights had to be reworked. The trigger action, with its rapid reset, was practically ideal for defensive work. But firing at an eight-inch bull at 50 yards was another matter. Trigger compression had to be lightened. The 1911 had been designed for reliability above all else. As long as the locking lugs and barrel bushing were properly fitted, it didn’t matter if the 1911 rattled when shook—it would place five rounds of service ammunition into a five-inch group or better at 25 yards.

The original military accuracy standards were for the 1911 to group five bullets into 5 inches at 25 yards and 10 inches at 50 yards. Most would perform slightly better. This is generous by modern standards but the 1911 was a comparatively accurate handgun by standards of the day. For competition use the 1911 needed to be roughly twice as accurate or better. A 4-inch 50-yard group was needed—or even smaller. Army gunsmiths went to work. They polished and relieved the trigger action, fabricating lightweight triggers as they went along. Trigger compression was reduced from 6 to 8 pounds to 4 pounds or lighter. The barrel was welded up until it would not fit the slide, then the contact points carefully filed and polished into a tight fit. Target grade sights were fabricated. These sights were not often adjustable during the first attempts at a target gun, but they were large and easily acquired by the eye. The expense of such a handgun was prohibitive for civilian shooters. An Army gunsmith might work on the handgun for months, devoting his time to the team. But Colt took notice and introduced the first National Match handguns.

The factory National Match handguns received special treatment in fitting and trigger work as well as good high visibility sights. The original Colt was a great pistol. Over the years various fully adjustable sight combinations were used including the Stevens, Elliason and Bomar. The Gold Cup became more of a target gun than an all-around shooter. The slide was lightened about 1957. Many shooters did not like this as they preferred the original 39-ounce balance. The slide was lightened to facilitate function with lightly loaded target ammunition. The rear sight was attached to the slide by a pin that sometimes worked loose. Later the Colt Gold Cup’s weight was returned to standard. A rib along the top of the slide was added for a flat top look. Many of these modifications meant that the Colt Gold Cup was a pure breed target gun, but not necessarily an all-around service gun. This has changed in recent years. The new Colt Gold Cup is a great all around 1911 well suited to serous duty with its round top slide and dovetailed rear sight—but also a great target gun.

During this time many shooters preferred to build up their own 1911s, particularly in the day of the poorly attached Colt sights. If memory and research are accurate, when the Colt Gold Cup retailed for about $135 a good used 1911A1 could be had for $50. That is a lot of room to choose your own sights and grips and also pay a decent pistolsmith. The process I have outlined by which the GI gun became a target grade 1911 was clear and certain with no detours. The picture of a Camp Perry class pistol gradually developed as the pistolsmith plied his trade. Too often speculative ideas are given the same footing as well tested ones, and you cannot do that in producing a bullseye gun. The guns were similar and it was a combination of skill and luck that made the winner. My understanding and description of the physical world is based on science and history when I discuss the .45 ACP cartridge respect for the big bore handgun isn’t a generational whim. I am simply stating reality. The worst thing a student can do is to confuse theory and speculation with facts and evidence. I do not wish to obscure the fact that a pistol like the Remington illustrated was intended for combat use. Nothing has been done to make it less reliable, but the work has made the handgun more accurate and more useful. There is much evidence that tightly fitted handguns with less loose motion are more reliable and long lasting. The Remington 1911 began life as a service grade handgun during World War Two. Inspectors traveled in production plants with gauges to insure mil spec compliance. The ideas behind the Camp Perry gun did not occur in a vacuum. They came up as a result of the demand by marksmen for a gun that would shoot well. There is no circuitous path: it was straight to the workbench and tighten the pistol, add a National Match bushing, weld the lugs up and adjust the trigger. I have known such gunsmiths and they think in physical pictures on solid mechanical and mathematical footing. The performance of the pistol is derived from the application of these fundamentals. Yet it is a subtle revision of the old warhorse.

Camp Perry shooters are a special breed and so are the guns. A good eye and a firm hand coupled with hand eye coordination above the ordinary makes a winner at Camp Perry.

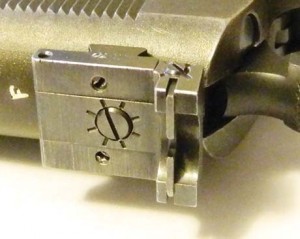

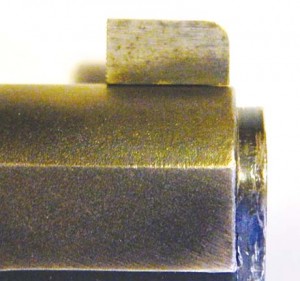

The 1911 has been called Old Slabsides or Old Ugly. The beauty of such a piece is more in the firing than the viewing, but the beauty of the 1911 is cold and austere. It is like a metal sculpture in that regard. The 1911 is nearly perfect as a fighting handgun and the spirit of delight and exhilaration in firing a target model is certainly evident. The exhilaration comes from hitting the target. Lately we have become accustomed to elevated, highly modified 1911 handguns and take high performance for granted. Progress in the intervening years since the Remington Rand was manufactured is evident, but the symmetry of progress owes much to such metal as the Remington Rand/Camp Perry gun. The pistol is fitted with a Micro-adjustable sight, what appears to be a handmade front sight, and a National Match barrel bushing. While the trigger has been replaced, the action remains heavy at 7 pounds. This was all that was needed to make a GI gun a target gun.

Firing the handgun is a joy and a revelation. Observing the pistol from the rear it is the same rugged 1911 but the well worn surface isn’t visible. Line the sights up and you see an excellent sight picture. Press the trigger correctly and you have a hit. I am not a trained bullseye shooter but have fired PPC, IDPA and Pin matches. So I know a little about the game. The pistol was well lubricated and loaded with Federal American Eagle 230-grain loads. I completely enjoyed firing it. Steel plates were addressed as well as silhouette targets at 10, 15 and 25 yards. The pistol feels solid in the hand and demonstrates good function. In testing for absolute accuracy, I fired a number of five-shot groups off of a solid bench rest at 25 yards with the Federal 230-grain Match load. Average groups were 2 to 2½ inches. The pistol is a joy to fire and use for a trained shooter. Both history and practical use are elements of pride of ownership, and this handgun has each. There are more expensive handguns, those that are better finished and some more accurate but none more pleasing to fire and own. Overall, a pleasing handgun and a great piece of history.

A big thanks to Steve Cooper of the CMP for images!