By Mike Nesbitt | Contributing Editor

Introduced in 1884 as the .38-55 Ballard, the cartridge which became known as just the .38-55 was one of the real headliners when it was at the height of its popularity, primarily as a target cartridge.

In single shot Ballard rifles it performed very well and it was winning prizes, especially in “short range competition” which is generally shot from 100 to 300 yards. It was quickly adapted to the Model 1881 Marlin which was the first lever action repeater to handle the .45-70. Today the .38-55 is possibly remembered as the very best of the original cartridges available in the Model 1894 Winchester as well as the Model 1893 Marlin.

My own background with the .38-55 involves the early Savage 1899, a rifle that treated me so well. That will certainly be mentioned more, although now my main interest in the .38-55 is in the new Highwall I recently received from C. Sharps Arms. But so far, I hope you can appreciate, I don’t have the experience with the new single shot Highwall that I had with the lever action Savage from so many years ago.

In a profile view, the .38-55 looks like a smaller version of the .45-70. The original loading of the .38-55, in the early balloon head cases, was with 55 grains of black powder under the bullet which was usually 255 grains. That’s where this cartridge got its name. Thicker and stronger cases with solid head construction have reduced the internal capacity of the cartridge so that later loads with black powder held 48 grains. And that much powder is just about a complete case-full which required compression before seating a bullet.

As a hunting rifle, the .38-55 was looked upon very favorably for deer and black bear, particularly in the woods and timber where long shots are not the general rule. We might say the .38-55 actually excelled in those areas. Several old references recommended this cartridge rather highly and the acceptance of the .38-55, especially in lever action rifles, was easily seen.

For example, all of the older single shot rifles which chambered the .38-55 had been discontinued by 1925 but the famous ’94 Winchester was still available in .38-55 caliber into the late 1930s.

Of course, today that outstanding life span is being extended even more due to the popularity of black powder cartridge rifles and loads which are currently being enjoyed. We might say the .38-55 was born again when re-introduced to Cowboy Action Shooting. Both Winchester and Marlin brought this cartridge back to life with new rifles being made for it. And, more recently, Cimarron Firearms has imported an Italian-made copy of the ’94 Winchester with the .38-55 as one of its chamberings. Winchester is not being out-done and they offer new versions of the ’94, made by Miroku, chambered for this old black powder caliber. It certainly isn’t hard to find a new .38-55 today.

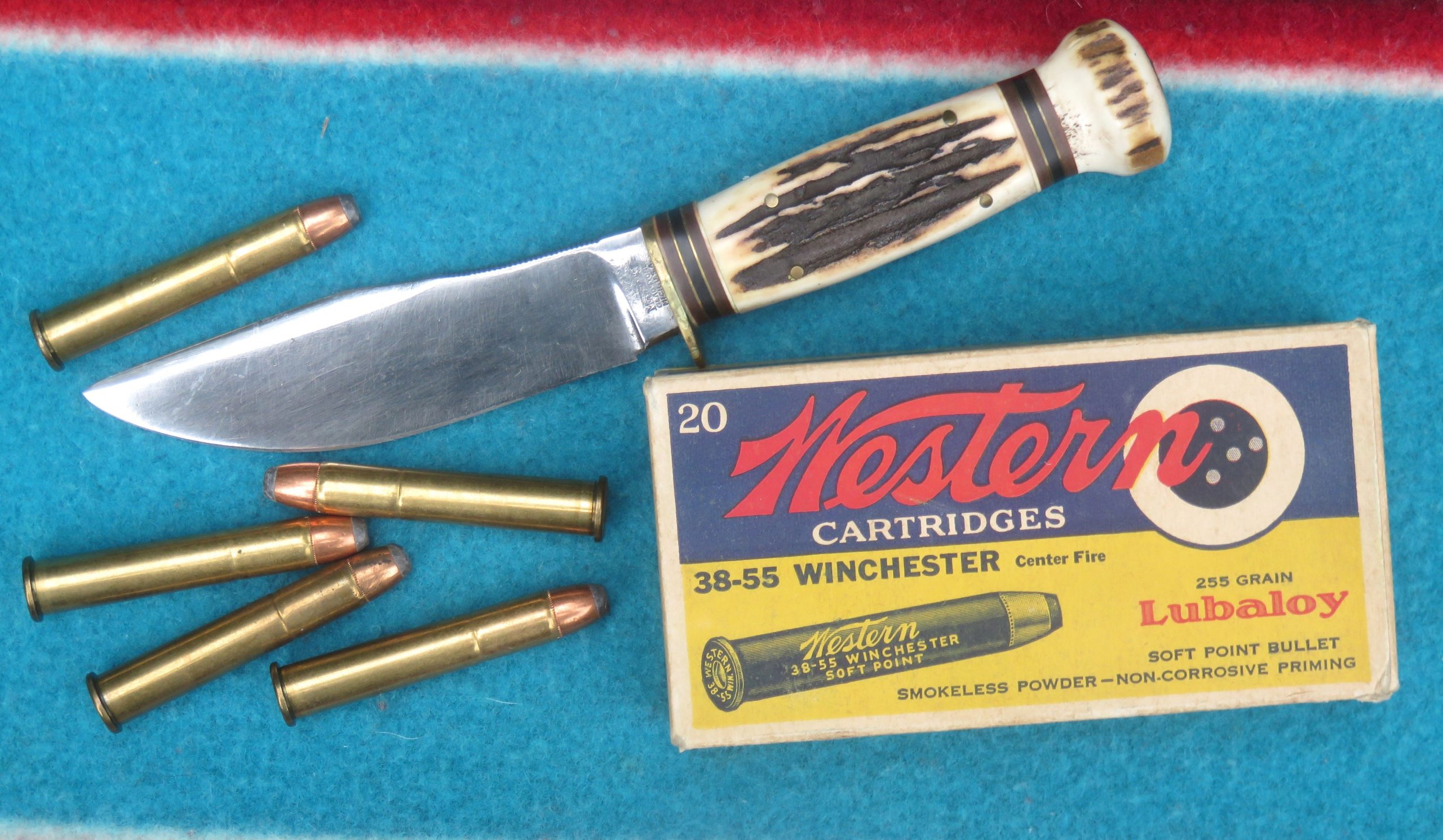

One of the things that gave the .38-55 such longevity was its adaptability to smokeless powders. The original black powder load was duplicated, velocity wise, with smokeless powder and that was referred to as a low-pressure loading. That fired the 255-grain bullet out of the muzzle at an advertised 1,320 feet per second. The most recent loads that I’m familiar with are still loaded to that speed. (Some of the Cowboy loads, for very short-range competition are even slower because most Cowboy events have some strict rules for velocity limitations.)

Smokeless powders, however, were often used to give the .38-55 a real boost velocity-wise and one example was the old .38-55 WHV (Winchester High Velocity) loading which fired the same 255-grain jacketed bullet at 1,590 fps. That was meant for strong actions only, such as the 1894 Winchester or the Highwall when equipped with the “Nickel Steel” barrel.

The most powerful loading for this cartridge was Remington’s .38-55 High Power which was loaded by U.M.C. (Union Metallic Cartridge Company). The .38-55 HP drove the 255-grain jacketed bullets out of the muzzle at 1700 feet per second. That might not sound terribly fast in this day of so many Magnums but it was certainly a meat-maker. One picture of its authority can be seen by noting that it had 1,170 foot-pounds of remaining energy at 100 yards which was 200 foot-pounds more than the standard loading has at the muzzle.

Several years ago, a good friend of mine bought a ’94 carbine in .38-55 with a nickel steel barrel and used it very successfully as a deer rifle. His method of hunting was to determine where a good deer trail was, then climb a tree close to it and wait. When a buck that satisfied him came by, and he always seemed to bring in some very big deer, he’d shoot it from above and basically point-blank range. Those 255-grain jacketed bullets, even at the velocities of low-pressure loads, always performed very well.

That helped spur my interests in getting a .38-55, which I did in more ways than one. The old .38-55 that I liked and used was a Savage Model 1899 “Saddle Gun” with a 22-inch barrel. My ammo for that rifle used the 255-grain jacketed bullets but I loaded them up a bit to try duplicating the higher velocity loads that had been factory available.

The only deer I got with that Savage was a fine blacktail buck taken in Oregon. My shot was made at 104 yards (paced right after the shot) and following the report of the rifle I clearly heard the “smack!” of the flat-nosed bullet hitting the deer. I had held for a heart shot and the deer jumped just after getting hit, typical of a heart shot, then bounded away. He didn’t get very far and I was rather confident that he wouldn’t, of course he was dead when I got to him.

The bullet from the .38-55 had certainly done its job. But the hit, while not trying to brag, was almost perfect and basically any bullet placed so well would have done the same. Penetration, as you might guess, was complete and the expanded bullet was never found.

Even later I did some hunting with a Marlin chambered for the .375 Winchester and I’ll include that here because it was really nothing more than a .38-55 with even heavier loads. The .375 Winchester’s case is a bit shorter than the .38-55’s and the bullets protruded from the mouth of those cases so the two cartridges would have the same overall length. And actually, but don’t take my word for it because I’m guessing, the Marlin rifles in .375 Winchester would chamber .38-55 cartridges. Mine would.

One outstanding hunt where I carried my .375 Marlin was on a bear hunt with Hoyt Axton. Hoyt was using a .45-70 and after he had fired, the bear didn’t stop. So, Hoyt and I both continued shooting until the bear was finished and down. The only other hit I remember making with that Marlin lever action was on a coyote that was just unlucky enough to be seen.

Now, of course, my most common use for the good old .38-55 is with cast bullets and black powder loads. The new Highwall that I recently got, which I’ve given the name of “Corky” will see a lot of shooting, with a real variety of black powder loads. The real variety will be in the bullet weights and styles. The common 250-grain bullet, Lyman’s #375248, will be getting a lot of use in that single shot. That’s the bullet I intend to use the most, for shots at 100- and 200-yard targets. For longer distance targets I do have bullet molds for a 330 grain New Postell bullet from Steve Brooks and another Lyman, which casts a 335-grain bullet for those longer ranges. And for short range work, and I mean really short range, I do have the mold to cast the old .38-55 short range bullet which weighs 145 grains and was loaded over just 20 grains of black powder. In addition to those bullets and bullet molds, I have one of Tom Ballard’s adjustable molds for a .365-inch diameter paper patched bullet for the .38-55. My favorite among those bullets is yet to be determined and my selection will be based on what kind of shooting is to be done next.

My loading for the .38-55 has turned slightly more complex since I began using black powder predominantly. One main change is that I now use a compression die, after the powder has been poured into the case, to force a wad, punched with a 3/8-inch cutter from milk carton sides, down for enough that the bullets can be seated without deforming them. So far, this is the only caliber I reload for that I have a compression die to use, and I use it with every black powder load.

The load I seem to favor the most uses 45.0 grains of Olde Eynsford 2F powder under the 250-grain cast bullets. Out of the 30-inch barrel of the Highwall, it produces an average muzzle velocity of about 1,260 feet per second. And five shots were tried using the same bullet but with 45.0 grains of Olde Eynsford 1 ½ F powder and that took the velocity down to an average of 1,234 fps. That didn’t bother me but accuracy did not increase.

I then fired five more shots with the 275-grain paper patched bullets loaded over 45.0 grains of Olde Eynsford 2F powder and those cooked along at 1,261.5 fps, almost the same as the 250-grain bullets. Of course, the average I’m talking about were all based on small samples just to get an idea of how things were going. More “tweaking” will certainly be done.

The shooting with my new Highwall in .38-55 is going fairly well although I certainly expect it to get better. A lot of us have the goal of shooting a ten-shot group on the 100-yard target that scores 100. I just did better than that with this new .38-55, shooting ammo with three different loadings and two different bullet styles, and got a total score of 102. That pleases me, even if it did take me fifteen shots to do it.

Presently, the shooting I’ve been doing with my new .38-55 will not support the legendary success that this fine cartridge is known for. But stay tuned, give me more chances. I’m going to give this new rifle plenty of chances and I strongly believe this will settle down, get broken-in, and perform with excellence. When that happens, you’ll hear about it.