By Mike Nesbitt | Contributing Editor

Almost any time we are reloading cartridges with black powder, we are going to need to compress the powder charge.

With black powder in cartridge reloading, powder compression is simply a normal thing. Where differences are found, however, is how that compression is done as well as to what extent it is done.

The simplest way of compressing the powder charge is to merely seat the bullet down on the powder, compressing the powder under the bullet. This can be very effective, but caution must be used because the amount of powder compression must be rather slight, or the force required will deform the bullet. There are some loads which I shoot quite a bit where I use this method of powder compression exclusively.

One of the most successful loadings where the powder is simply compressed under the bullets is in my .44-40 loads, where a 35-grain charge of Swiss 3Fg powder, which nearly fills the case to the brim, is compressed by seating the 205-grain bullets down to the needed overall length of the cartridge. Actually, some slight deforming of the bullets does take place, at the nose where the top punch in the seating die “swages” the top of the bullet just enough to give it a new form. While that deformation has been noticed, it has not been any problem, at least not yet. My .44-40 loads perform rather pleasingly.

Another load where I compress the powder slightly by seating the bullets down on the powder is in my .44 Russian loads, using 19 grains of Olde Eynsford 2F powder under the 250-grain bullets. In those loads, the amount of compression is not nearly as much as it is with the .44-40s but that still is enough to take notice of.

One more load, just to mention another favorite, is the .44 Colt. In that cartridge I use a 220-grain bullet over 21 grains of Olde Eynsford 2F powder, compressing the powder slightly when seating the bullets. No problems there.

A rifle load, larger than the .44-40, where I commonly compress the powder by just seating the over-powder wad and bullet down on it is in my .44-77 cartridges. Perhaps it is because of the bottleneck cases but the powder seems to be easily compressed and the bullets, when seated by using the seating die, do not show evidence of being deformed or even marked. And I can say the same thing for most loads in my .44-90 cartridges.

When I say, “most loads in my .44-90 cartridges,” I mean the loads with 90 grains of powder. To increase the powder charge, remembering that the .44-90 Sharps was often loaded with 105 grains of powder, then the powder needs to be compressed prior to seating the bullets or the bullets will be deformed, perhaps severely enough to prevent the loaded rounds from entering the rifle’s chamber.

Sometimes compression of the powder charge simply can’t be done, at least not easily. This brings to mind my reloading of the .32 S&W cartridges for shooting in an old Smith & Wesson five-shot revolver. The old factory load for those little .32s used 9 grains of powder beneath the 85 grain bullets. When I first tried making loads for that cartridge, I found that a full case was about 7 grains of the Olde Eynsford 2F. That was certainly too much powder to compress by seating the bullet over it. I had no compression die, which we’ll talk about in just a little bit, so seating the bullets over the powder was my only choice. The powder charge was reduced to 6 grains and that was too much as well. With the 6-grain powder charge, the bullets became too deformed to chamber in the little S&W’s cylinder. So, a 5-grain load of powder was tried and that worked successfully, in fact, very well.

Most of the time when I’m loading ammo where the powder must be compressed before the bullets are seated, I just use the standard expander die as a compression die. This will work when compressing the powder charge under an over-powder wad, such as the “veggie wads” from John Walters. To do this, the expander die is backed-off and then readjusted to push the wads down to the desired depth. Determining that depth is easily done by measuring the depth of the wad and comparing that to the side of the bullet which will be seated over the wad. To do that I just use a small Allen wrench, insert it into the case mouth and hold my thumbnail against it to show that depth, then hold that against the bullet which will tell me if the wad is deep enough, too deep, or at the right depth. Once the depth is found, charge the cases with powder and compress those powder charges under the wads. Following that, seat the bullets so the bases of the bullets will rest right on top of the wads. Using the expander die in this way isn’t too bad but the wads being used must be rather rigid, so .060” thick wads are the best choice.

If the wads being used are not rigid then using the expander die as a compression die is not a good idea, and I can speak from experience about that. Rather recently I began punching my own wads out of milk carton material. Those look rather rigid but when used to compress the powder, in a .50-70, the milk carton wads tend to conform to the rounded “nose” on the expander die which makes the wad, resting on top of the compressed powder, look like a shallow cup. When bullets are seated down on that cupped wad, there will be a small air pocket beneath the bullet. That is unless the bullet is forced down on top of the wad hard enough to let the wad conform to the base of the bullet, but that would take us right back to deformed bullets.

The small air pocket beneath the bullet is not anything that leads to danger; it isn’t that big. And it will be alleviated basically before the bullet completely enters the barrel of the rifle. However, it won’t give the bullets a consistent start and that can lead to inaccurate shooting.

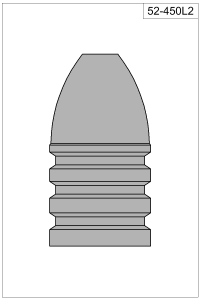

To give this a little test, I had several rounds loaded with the milk carton wads for my .50-70 Sharps. The load used 65 grains of Olde Eynsford 2F powder, the milk carton wads, then a bullet from Accurate Molds’ #52-450L2, lubed with BPC from C. Sharps Arms. And ignition was supply by Winchester large pistol primers. For my test, more ammo was loaded using all of the same ingredients except for using Walters’ Wads of .060” thickness with a diameter of .512”. That wad diameter is the same that I size my cast bullets to for the .50-70. It has been my experience that you don’t want a wad that is of larger diameter than the bullets being used. That can also lead to inconsistency. And, for identification, the loads with the Walters’ Wads had their primers dotted with a marking pen.

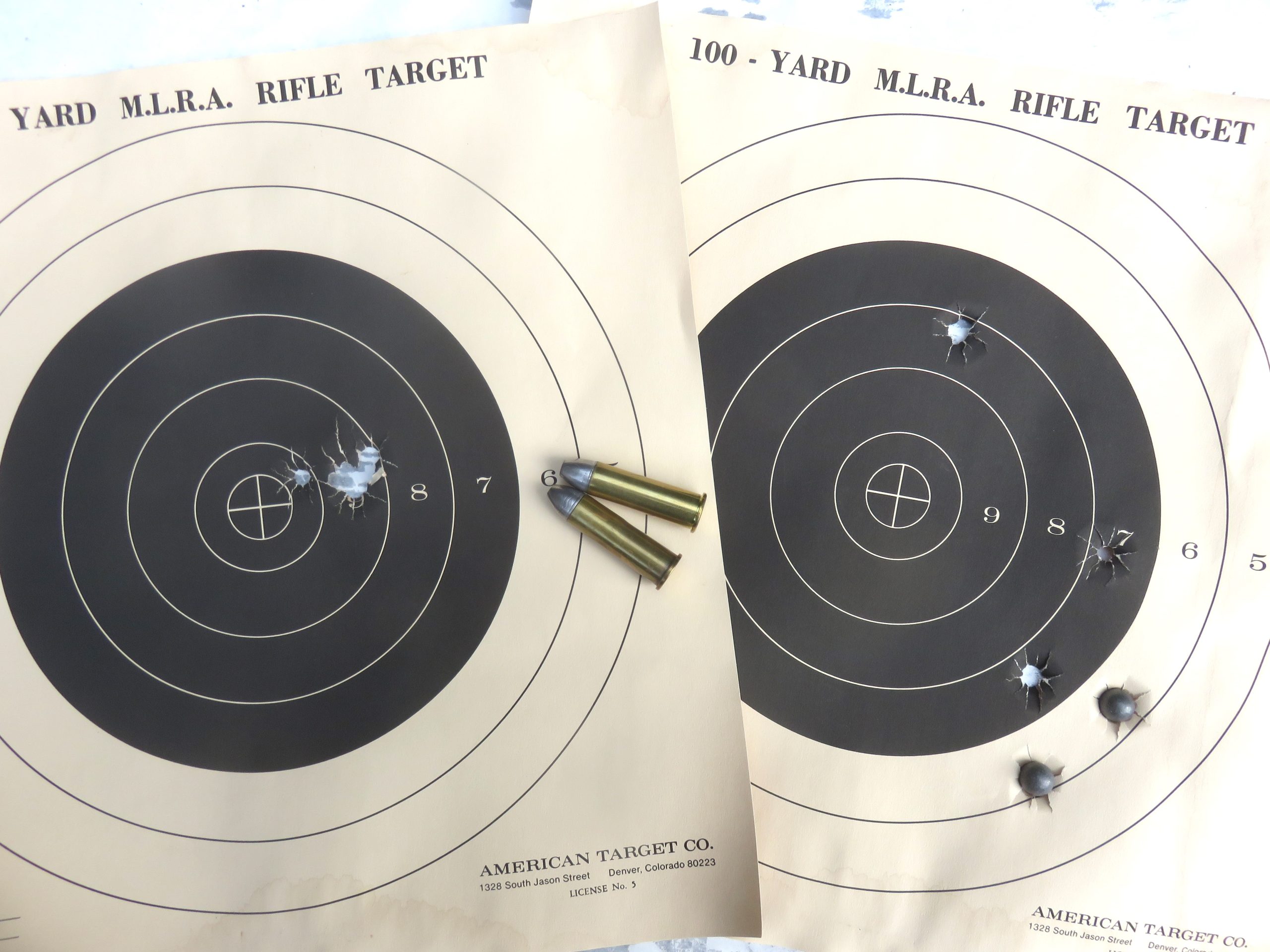

For this test, I posted two targets side by side at 100 yards. The shooting was all done from a benchrest to take as much of the human factor out of the test. To begin with, I fired one shot simply into the dirt with an extra paper patched load which I had just for that purpose. That was a fouling shot, just fired to put a coat of lube in the barrel. Then, after using the blow tube, I selected one of the marked loads and fired it at the lefthand target. Following that, after using the blow tube again, one of the unmarked loads was fired at the righthand target. This was done so the rifle’s barrel would not be more fouled or dirtier for one target than the other, and the same sequence continued until each target had been shot at five times.

While shooting for this report, no spotter or spotting scope was used. I didn’t want any influence from the targets before the shooting was completed. All I did was to try my best with each shot, trying for good groups. You might think the results were ‘rigged’ but I will swear they were not. And I was as surprised as anyone when I hiked out to retrieve those targets.

The lefthand target, which absorbed the shots with the Walters’ Wads, held one 10 and four 9s, almost one jagged hole. But the righthand target, which used the milk carton wads, had shots scattered including two shots that missed the black. We’ll have to agree that the contrast between those two targets is enormous.

For this test, the Walters’ Wads used for compressing the powder charge certainly won. My very first step after doing this shooting was to order more of the Walters’ Wads and I ordered them from Buffalo Arms Company, a favorite supplier for black powder shooting products. They are easily reached by email at www.buffaloarms.com.

Here’s what they say about them, “Walters Wads used in black powder cartridge loads and long-range black powder muzzleloading. These vegetable fiber wads placed between the powder and the bullet will protect the base of your lead bullet from burning black powder and improve accuracy. Used by champions!”

Walters’ Wads can also be ordered directly. John Walters makes these vegetable fiber wads in almost all calibers and in several thicknesses, from .25 caliber to 10 gauge, and they are recommended for black powder cartridge rifles, cowboy action shooting, muzzle-loading, and for Schuetzen competition. His wads are available in .010”, .015”, .030” or .060” thicknesses and they are priced at $20 per 1,000 plus shipping and handling. Contact him by email at thetinwadman@cox.net. His mailing address is; John Walters, 500 N. Avery Drive, Moore, Oklahoma 73160 and his telephone number is 405-799-0376.

But getting more Walters’ Wads for the .50-70 isn’t all I’ve done. I’ve also ordered a compression die plug from Buffalo Arms Company and I will certainly give the milk carton wads another chance when they can be properly seated flat while using them to compress the charge of powder. That will be reported later and, in fact, I’m rather buzzed about it.