By Mike Nesbitt | Contributing Editor

The .45-70 Government is one of our most popular cartridges for either black or smokeless powder.

That’s more or less simply a statement which repeats the obvious because there are only two other cartridges that can share the honors of being in constant production, at least for the ammunition, for over 150 years. Those other two cartridges are the .45 Colt and the .44-40 Winchester, both of which should get more attention here. But for now, we’ll try to concentrate on just the good old .45-70 in single shot rifles.

But somehow, we simply can’t just start at the beginning. The .45-70 has too much history behind it to not comment on the variety of loadings which were or still are available for this remarkable cartridge. Early in the era of smokeless powder, the .45-70 was offered in high velocity loads and similar loads are offered by the ammo factories presently. Various bullet weights are still being offered and the .45-70 cartridges, over the years, have been available with bullets weighing from 148 grains (the “collar button”) to 500 grains. The most popular, for both black powder and smokeless loads, have been bullets ranging from 300 grains to 405 grains.

Over this cartridge’s 150-year life, it has been loaded in a lot of ways and it has done a whole lot of things, from being our county’s main government cartridge to being a fine sporting round. Now, after giving recognition to the .45-70s triumphs and its history, we’ll try to concentrate on the very early loads for this remarkable cartridge.

The original .45/70/405 loading was developed at Frankford Arsenal in 1872. The bullet weight was just 400 grains at first but that was changed to 405 grains in the midst of the trials when it was found that adding a fifth bearing band and the fourth lube groove to the bullet improved accuracy. That information came from Lyman’s Centennial Journal of 1978 and the 405-grain bullet with the four lube grooves was very similar to Lyman’s #457124. The only difference that I can see when a new Lyman mold for #457124 is compared to the old sketches of this bullet’s design is in the rounded bottom lube grooves while the early design had flat or square bottom grooves. (I do prefer the square bottom grooves because they hold more lube. But the round bottom grooves do drop from the mold easier.) After those Army trials, the .45/70 was adopted in 1873.

That original loading is easily duplicated using the Lyman bullet or one of similar weight, seating it over 70 grains of compressed black powder. For a first try, I’d recommend either Swiss or Olde Eynsford 1½ F powder and that granulation of powder could be quickly changed to meet with the shooter’s or the rifle’s taste. One thing you might quickly learn about that load is why the Army decided to also make a carbine load, which could be more easily handled in guns weighing less than the full-length trapdoor Model 1873 Springfield rifles.

The carbine load, with the same bullets from #457124, when cast with a soft lead allow, such as 30-1 lead-tin, is my favorite. These are loaded with 55 grains of Olde Eynsford 2F powder which duplicates the old carbine load, and it is simply a nice light load, good for shooting all day without cleaning. When you shoot it all day, this load leaves you with a fairly good feeling shoulder too. While that is simply the carbine load it is still a good load for hunting, perhaps for deer sized game at ranges within 100 yards. It is not a long-range powerhouse, but it doesn’t lack a whole lot either.

To reproduce the carbine loads, simply charge the primed cases with the 55 grains of your choice of black powder and seat the bullets deeply enough to eliminate any air pocket beneath the base of the bullets. At first, the Army seated the bullets in the carbine loads deeper than in the rifle loads so the two loads could be identified at a glance. Later, after the cartridges received headstamps, they were loaded to the same depth but with an “R” or a “C” depending on whether the load was for rifles or carbines.

If there was ever an absolutely classic bullet for the old .45-70, it has to be the old Lyman/Ideal #457124. Lyman has dropped many molds over the years but thankfully #457124 is still on their list, it’s just too good to ignore. Lyman’s bullet molds are available from almost any handloading supplier. (Buffalo Arms Co. lists it for $92.69 without handles, look for it at buffaloarms.com.) If you want to contact Lyman more directly, perhaps to request their catalog, write to them at; Lyman Products Corporation, 475 Smith Street, Middletown, Connecticut 06457. Also, take a visit to their website at www.Lymanproducts.com.

While we’re discussing some history, the 500-grain loads for the military were not introduced until 1881. One potential purpose for that heavy bullet, at least for the military, was for firing on mass columns of troops at 2,000 yards away. That load was identified at the .45-70-500 and the copy of that bullet can be cast with Lyman’s #457125, still good for long range. We can duplicate that load by using the heavier bullet but the 70-grain powder charge does need to be compressed under a card wad more than with the 405 grain bullets simply to get the 500 grain bullets seated properly. Several shooters who use this bullet seat it over 63 grains of their favorite powder and find it very effective for mid-range target work, out to 600 yards or further.

The bullets used for these carbine loads were Lyman’s #457124, the old Ideal style of grooved bullets that were the standard 405 grain slug for the .45/70. Some of the old-style bullets did have fewer and wider lube grooves but those don’t show once the bullets are loaded into the cases. And the bullets for the carbine loads were seated rather deeply, so no air space was left in the case above the powder charge and to make the carbine loads instantly identifiable to the shooters. That can be duplicated by seating the bullets deep enough so the mouth of the case could be slightly crimped over the “top” of the forward driving band.

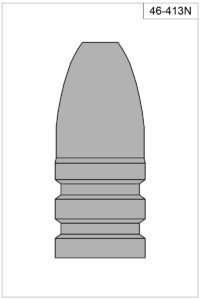

Shooting the carbine load in this light rifle is a real blast and I would certainly continue using that load except that something new has come my way. That “something new” is a new bullet and it is this new bullet that has caused the rebirth in my interest in shooting this caliber. If I haven’t already told you about bullet number 46-413N from Accurate Molds, I certainly should have.

This was born after seeing pictures of an original Sharps bullet mold for their 400 grain bullets in Roy Marcot’s latest book on Sharps Firearms, Volume III. The old Sharps bullet mold was a nose pour design with the large spur cutters. That was one of the Sharps offerings for the .45-70, a 400-grain “naked” bullet that was 1 1/10-inch in length. Earlier Sharps had offered a 412-grain “naked” bullet and I think those two bullets were actually the same, perhaps with deepened lube grooves to take it down to 400 grains.

The main features about this bullet are that it has two large lube grooves with a rather long nose, so the bullet protrudes beyond the case mouth much further than with bullets made for the lever action repeaters. (A repeating rifle for the .45/70 did not appear until Marlin introduced one in 1881.) That longer nose bullet gives these loads a real “Sharps” look to them, suggesting that the cartridge boxes should be labeled with “Put Up Expressly For Sharps Rifles” like they used to be. For more info on Accurate Molds just go to their web site at www.accuratemolds.com.

I size this bullet to .459” diameter and it seems to be working just fine. The lube I like is BPC from C. Sharps Arms and for powder I’m using 65 grains of Olde Eynsford 1½ F, with an .030” Walters’ wad between the powder and the base of the bullet. The only other detail I can give you about the load is that it gets its ignition from standard Winchester large pistol primers.

Another shooter who has used 46-413N, more than I have, is Mike Moran and we often partner at practice and shooting matches. He loads this bullet over a full 70 grains of Olde Eynsford 1½ F powder and gets very impressive groups with it. Mike has also used his loads with this bullet at longer ranges and continues to do well with it. For those long-ranges, a heavier bullet will have advantages, of course, but the 413 grain bullets do perform well enough and Mike considers it his “all around bullet” for his .45-70 Sharps.

In this review of duplicating some of the early loads for the .45-70, we’ve only talked about using the grease-groove bullets. That’s perhaps, only half of the story. There were more paper patched bullet loads back in the days when the .45-70 was only used in single shot rifles. Next time we join in conversation about the bullets and loads for the .45-70, we’ll focus on those paper patched bullets and how to make the loads for them.