By Mike Nesbitt | Contributing Editor

One very popular aspect about black powder cartridge rifle shooting, often referred to as BPCR, is long range shooting.

To be technical about it, long-range shooting is where the targets are at 700 yards and beyond. To continue with definitions for a moment, short-range includes targets out to 200 and sometimes 300 yards. Mid-range shooting has targets located out at 300 to 600 yards. Getting good hits at any of those ranges is certainly gratifying but doing well at long-range is especially rewarding after the needed practice and load development.

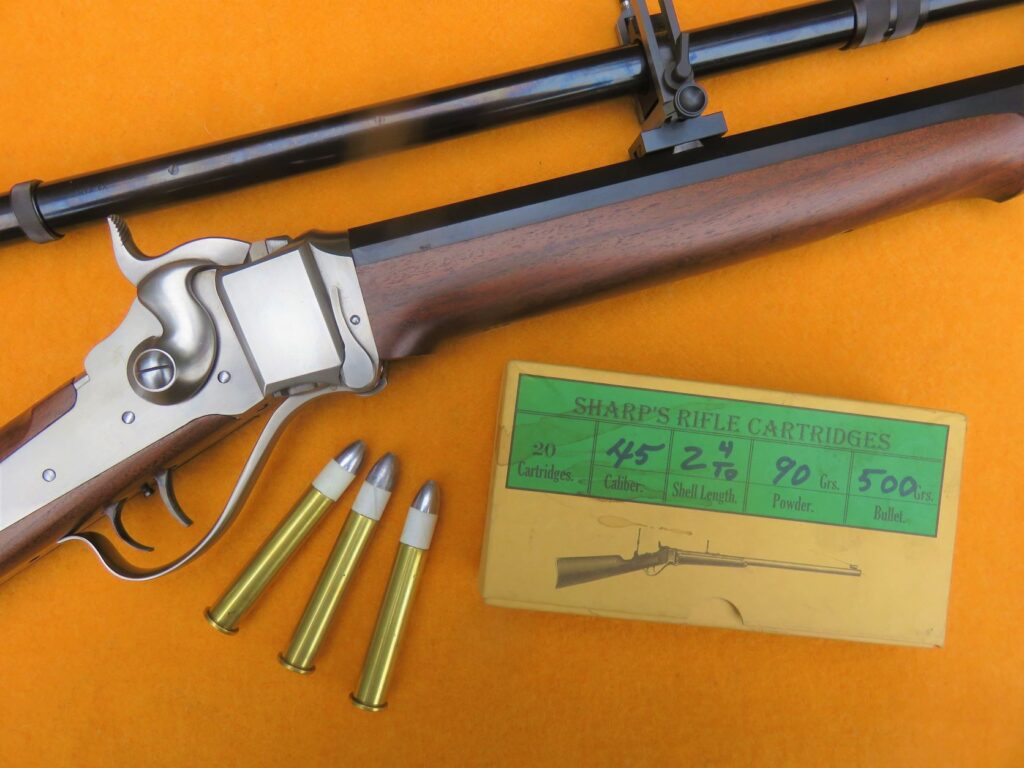

My own tastes and habits for long-range shooting have changed recently which can be seen in my newer rifle as well as the sights on that rifle. Previously my 1000-yard rifle was a Model 1874 Sharps (that should be no surprise) in .44-90 caliber with a 32-inch-long barrel. I still have that rifle and it stands ready to be used again. Now, however, that .44-90 is in the rack next to a heavier Bridgeport Model Sharps, also by C. Sharps Arms, with a 1 ¾ heavy barrel, 30 inches long, in .45-90 caliber. It’s the .45/90 that I’ll be talking about the most as we continue.

Historically, Sharps introduced what we now call the .45-90 in mid-1877 as the .45-2.4” Sharps and they usually loaded it with 100 grains of powder under a 500 or 550 grain paper patched bullet. This cartridge was intended for target shooting and was not generally chambered in sporting rifles. It actually replaced the .45-2.6” Sharps which had the same loadings. (The sporting rifle load that Sharps had introduced in 1876 was the .45-2 7/8” Sharps, which today we refer to as the .45-110 Sharps, that’s the cartridge featured in the movie “Quigley Down Under.”) The general reference to the .45-90 Sharps, in today’s terms, coincides with the .45-90 Winchester which was introduced in 1886 as one of the first cartridges for their Model 1886 repeating rifle and has, generally, the same dimensions for the brass case. While the case is basically the same, the Winchester load used a rather light 300-grain bullet for an express load, with high speed but for short range, and the Sharps loading used the 550 grain bullets for long-range shooting.

Loading for the .45-90 Sharps, or the .45-2.4” cartridge, is very easy and it is actually quite versatile. My paper patched loads include 90 grains of powder, and Swiss 1½ Fg is what I’m using most of the time now, under a 500-grain patched bullet which was cast in a tapered Ballard mold. That’s the load I like to consider for hunting even though I’ve never used it for that purpose. Maybe my dream is to roll an antelope over with that at a reasonable range. We’ll have to see about that…

The load that gets used the very most, however, is the loading that performs well at long-range, using a 550-grain grease-groove bullet from a Hoch mold, over just 70 grains of the Swiss 1 1/2Fg powder. Another shooter commented that the .45-90 cartridge can so easily be loaded with full “.45-70 loads” with very little compression of the powder and that is true. In my rifle, the 550-grain bullets group nicely and with that kind of performance, I don’t care how fast the bullet is going.

For accuracy at long-range we need to tweak our bullets and loadings to have consistency and stability. My bullets for the .45-90 and others are cast with a 25-1 lead and tin alloy, which I buy from Buffalo Arms Company (www.buffaloarms.com). Those bullets are sized to .459” diameter and lubed with BPC bullet lube which is a product of C. Sharps Arms Company (www.csharpsarms.com). (You should have the addresses to those web sites almost memorized by now, I do mention them over and over.) Those big bullets are almost 1 ½” long and they have large generous grease grooves which carry a lot of lubricant. In other words, it was made for shooting with black powder. The nose of the bullet is wide enough that it rides the lands of the rifling while the rings between the grease grooves fill the rifling grooves very completely. Those features add to consistency because the bullets should enter the rifling the same with every shot. We might say that the bullets must enter the barrel in a consistent way if they are to leave the muzzle with consistency.

Stability, of course, is the product of having the right rate of twist in the barrel’s rifling for the bullet that’s being used. This .45-90 rifle has a 1 in 18” rate of twist which is rather typical for today’s .45 caliber black powder cartridge rifles, .45-70 and larger. If the bullet has a weight (actually the bullet’s length is the key) that was not well suited for the barrel’s rate of twist, we might find that the bullets could lose stability at long-range, if it was ever stable to begin with. If a bullet becomes unstable in flight, it simply loses its sense of direction and common evidence of that is finding “keyholes” in your target, made from bullets going through the paper sideways. Without stability, accuracy is lost at any distance.

As you can see, my comments about a long-range loading are for the most part mentioned in general with some specific points made for the .45-90. Every shooter assembling long-range loads will have a number of “tweaks” to be made while developing the load which will make the ammo specifically suited for just one rifle. It is quite common for shooters with two rifles of the same caliber or chambering to have different loadings for each of the guns.

My .45-90 rifle has been briefly described but let me tell you a little more about it. This gun was built with long-range shooting in mind and, complete with its 6X scope by Montana Vintage Arms (www.montanavintagearms.com), it weighs 14 ½ pounds. (It’s even heavier when it’s loaded.!) Having the rifle that heavy helps for steadier shooting, even offhand. The weight also reduces the effect of recoil and the heavily loaded black powder cartridge rifles can kick.

In order to give you an example of the accuracy this rifle and load is giving me, I’ll tell you about some shots fired recently in a silhouette match. There isn’t a 1,000-yard range that is conveniently close to me so I enjoy shooting the silhouette matches for practice and the rams, the farthest targets, at these matches are set at 500 meters, or almost 550 yards. For that distance, those rams are actually small targets and the entire silhouette match is very challenging.

One very important part about silhouette shooting is having a partner for a spotter. The spotter watches the target through a spotting scope and reports to the shooter where the shot had gone, hit or miss. And those hits are reported on, where on the animal silhouette the hits were made. The spotter is important enough that in some matches, when the shooter is awarded, that shooter’s spotter is also awarded because the shooter couldn’t have done so well without the spotter doing an excellent job.

For this example, my spotter was Steve Morris, a very well-known silhouette shooter and a member of the Master shooting class. Having Steve spot for my shots was a real treat and he is certainly an inspiration, encouraging me to do my best. He wasn’t shooting that day (and I don’t know why), he was just spotting for me.

With Steve’s help, I did quite well. We started on the chickens at 200 meters, shot offhand, and I got two of the little critters. Next, after waiting for the second relay to shoot their targets, we moved to the pigs at 300 meters (about 330 yards). Most silhouette shooters do their shooting prone at all targets except the chickens but I prefer to shoot sitting behind the cross-sticks. (That’s how the shooting is done at Quigley.) On the pigs I got eight, knocking down four of both groups of five. Then we moved out to the turkeys at 385 meters, almost 425 yards. After getting a good sighter shot, I fired for score, hitting all five in the first group and winning a “5-pin” for five straight hits on turkeys. In the next group of five turkeys, I clobbered two more for a total of seven.

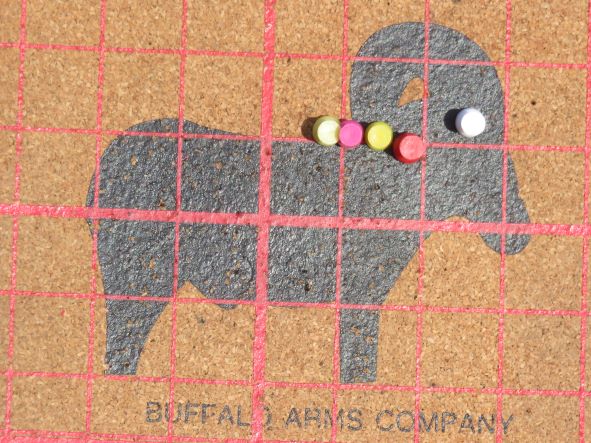

This silhouette match ended with the shots at the rams. On the first bank of five rams, I got only one. It is a real treat to fire at a target at that distance and watch it fall a good two seconds after the shot was fired. That is approximately the travel time for the bullet, which starts with a muzzle velocity of about 1,200 feet per second, to cover that much distance. On the next bank of five rams, I got more serious, with Steve’s help. There I got three rams in a row with close misses on the last two. For me, that was a very good day on the silhouette range.

Steve kept track of my shots on a spotting board and I’m including a picture of that board to show how well my shots went on that last bank of rams even though two of the shots were misses. The pins show where the shots went and, in this case, they go from right to left, with the last two shots going over the ram’s back just behind the neck. If those shots had been made on a paper target, they would be in a rather nice group.

While my shots at the rams were not fired at “long-range” according to strict definitions, those shots certainly performed well and I’m going to keep in practice with this .45-90 rifle while using that load by doing more shooting. You might have guessed that my real intentions for this rifle and load have a “buffalo” (a full-sized steel silhouette) at 805 yards as the real priority. That will be at the next Matthew Quigley Buffalo Rifle Match and maybe I can talk Steve Morris in going with me.