By Mike Nesbitt | Contributing Editor

The suggestion came to me to write an article about black powder cartridge reloading and while thinking about that, it would be very difficult to do just one article on this rather wide subject with any detail.

That’s why I’m beginning a short series of articles on black powder reloading, starting with the revolver cartridges. I hope you will agree that this is a practical place to begin.

In fact, the “old” revolver cartridges were all designed for use with black powder. And our last cartridge designed for black powder was the .44 Special, introduced in 1906. Yes, it was also available with smokeless powder but its black powder factory loads used 26 grains of powder under the standard 246 grain bullets. Likewise, the .38 Special was also a black powder cartridge and that used 21 grains of the “black stuff” under its 158 grain bullets. So, shooting black powder loads in most of the old revolver cartridges is simply normal.

It might be interesting to know that the very first revolver cartridge designed for use with smokeless powder was the .357 Magnum, introduced in 1935. Several other handgun cartridges were introduced before the .357 but those were primarily all for the semiautomatic pistols which were the real rage back then.

So, let’s dive into this subject with some notes on reloading the smallest black powder cartridge that I have experience with, the .32 Smith & Wesson. This little sweetheart came into being in 1878 and it gained popularity very quickly. Smith & Wesson’s history and success is based on the little revolvers and not their big boomers.

Starting with the .32 S&W is good in another way too because with this small cartridge we must speak of something that is normal with almost all reloading with black powder, powder charge compression. Some handloaders use compression dies when they are assembling black powder loads but for most of my reloading, I don’t use the compression dies. One way to compress the charge of black powder is to simply put the bullet over the powder and compress the powder as the bullet is seated. That can be done but it must be done carefully.

The problem with compressing the powder charge by simply seating the bullet on top of it is that the bullets are easily deformed when using this process. Let me explain this with more detail by discussing how I loaded my .32 S&W cases. Just please note, the problem of deformed bullets is not exclusive to the .32 S&W.

There is another generality to get out of the way before we get specific on loads. We’ll do all of our shooting with cast or swaged lead alloy bullets which are lubed with a black powder lube. This means no jacketed bullets. Also, the relatively new coated bullets won’t be used either. The coating might prevent leading but it probably can’t keep black powder fouling soft and that’s the important thing. Black powder bullet lube is needed to keep the fouling soft for the next shot and without it your accuracy is lost after just three rounds.

Before you start loading black powder ammunition, get some black powder bullet lube. The best places to get that are from; C. Sharps Arms (csharpsarms.com), SPG Sales (blackpowderspg.com), or Buffalo Arms Company (buffaloarms.com). We can quickly add other sources, such as Dixie Gun Works or Track of the Wolf. Shop with your favorite suppliers, certainly. I only mention these specific places because black powder bullet lube can seem to be hard to find on the general market. Which lube to select is up to you but be sure it is made for use with black powder.

Brass is another subject which has some specific treatments for reloading black powder ammunition. But let’s save that for now and simply begin with new brass.

The brass we’ll focus on to begin with is from Starline; brand new cases. Starting with new brass can be considered a standard for all revolver calibers but for at least a little bit we’ll give specific attention to the .32 Smith & Wesson cartridge.

The .32 S&W is somewhat outstanding to me, that’s the smallest cartridge I’ve loaded with black powder. Of course, it was originally a black powder cartridge and notes in the old books tell me that the factories loaded it with as much as 10 grains of powder under the 85 grain lead bullets. Lee Precision made the dies I use and my bullets are cast with a Lyman mold, #313249. Those bullets are pan lubed with BPC and then they’re ready for loading.

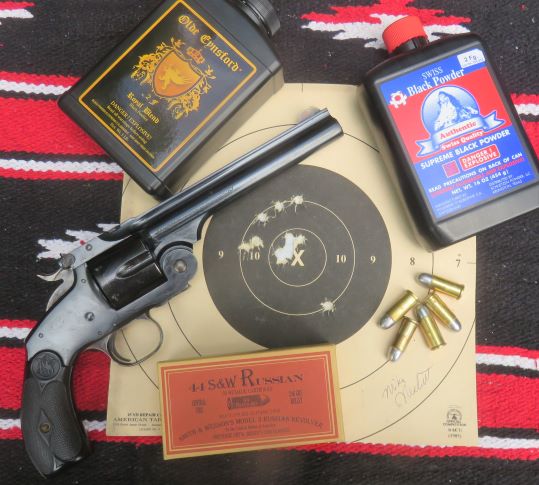

A compression die could be made for use with the .32 S&W ammo but I didn’t feel that was really needed. Instead, I would simply compress the powder charge while seating the bullet. My first try was with just 7 grains of powder, measured by weight. That was too much and the bullets were deformed while being seated. Those were pulled and another try was made with 6 grains of powder, using GOEX’s Olde Eynsford 3F powder, but that was also too much. Those loaded cartridges looked good but the bullets had been deformed just enough that the loaded rounds could not be chambered. Next, the powder charge was reduced to just 5 grains and with that the bullets still slightly compressed the powder but actually loaded easily. Shooting them is a lot of fun.

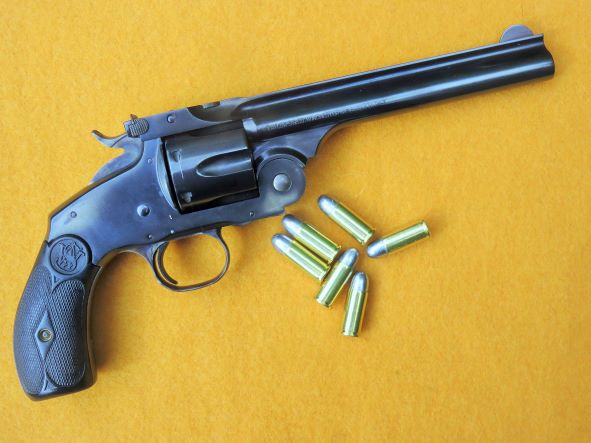

More shooting, which is actually more fun, is done with the bigger bores. In this area I personally favor the .44s, with the .44 Russian and the .44 Special at the top. For bullets I prefer to get bullet molds made to copy the old original bullets for those calibers and in the .44 Russian I use Lyman’s (discontinued) #429184 which weighs about 250 grains. In the .44 Russian I use 18 ½ grains by weight of Olde Eynsford 2F powder underneath that bullet as a target load. That powder charge receives very little compression and the bullets are in no danger of being deformed. The old standard loading for the .44 Russian used 24 grains of powder so my target load is beneath that and the most powder I’ve used in reloading those cases was 22 grains.

Modern brass is generally better made than cartridge cases from years ago and, equally in general, they won’t hold as much powder as the old cases. That’s especially true when you compare new “solid-head” cases with the old “balloon-head” brass. Balloon-head cases did hold more powder but the solid-heads are better in every other way.

Not too long ago I used some balloon-head cases for the .45 Colt to see how they’d work. Those were loaded with a full 40 grains of Swiss 1 ½ F powder under the 255-grain bullets from Lyman’s #454190. That should have duplicated the old Colt load from 1873. When I touched the first one off in my old (2nd generation) Colt with the 7 ½” barrel, I had to exclaim “Holy frejoles! Batman!!” That was a black powder magnum if there ever was one and that bullet crossed the chronograph at almost 1,020 feet per second. (No wonder the Army reduced the service load to 28 grains.) For the .45 Colt I personally favor using .45 Schofield cases which are available from Starline with about 24 grains of Olde Eynsford 2F powder.

Now, for treatment of the fired brass. Those dirty cases must be cleaned and it is best to de-cap them with a separate de-capping pin, available from Lee, and then soak the brass in soapy water. Almost any soap will help, I generally use a liquid dishwashing soap, just a little bit. Some reloaders shake the jug of soapy water with the empties in it and I more often use a case cleaning brush (available from Buffalo Arms Company). Then the brass must be dried and driers are made but I usually just let my cases sit on a paper towel overnight. In the morning those cases are usually dumped into a tumbler for more cleaning, although they can be reloaded as long as they are dry.

For powders, most revolver cartridges can be reloaded using Olde Eynsford or Swiss 2F or 2Fg black powder. FFFg, commonly shown as 3Fg, is a finer granulation which might be finer in the smaller calibers and that’s what I use in the .32 S&W. Finer powders, such as 4Fg, should not be used for anything except as a priming powder in flintlocks.

Black powder is easier to ignite than the smokeless powders so special primers are not required. Sometimes modern magnum primers get used in my black powder loads but that is because they were more available than for any reason of need. Standard primers will give excellent and consistent results.

For bullet selection, I’ve already stated how I like to use copies of the original bullets. That choice is based on more than just shape. Black powder loads basically require plenty of bullet lube and the old designs can have larger grease grooves than the more modern styles. Not using enough lube will result in loss of accuracy after firing a few rounds which won’t be restored until the gun is cleaned again.

Well, we started this conversation with some generalities, then got specific for just a little bit, and we’re ending with more generalities. There are no specific tools needed for reloading with black powder other than the bullet mold for the bullets you might select and, should you feel you need to use one, a compression die for compressing the powder charge. In selecting a powder charge, let me suggest that you at least fill the case with powder so the bullet will rest on the top of the powder with no air space. That is not critical and, in fact, most black powder reloaders are more pleased with loads which do include slight compression of the powder.

Shooting revolvers with black powder loads is very enjoyable and rather habit forming. When first done, the revolver will be hard to clean but that gets easier to do very quickly. I guess those sixguns must “soak up” some of the black powder lubes or something. Just use a black powder solvent such as Three Rivers produces and sold by The Gun Works. My .44 Russian now gets cleaned with just two patches, barrel and cylinder included, and then oiled with one more patch. Our club, the Black River Buffalo Runners, holds black powder revolver matches where some very impressive scores are shot. So, try some revolver loads with black powder and we’ll “make smoke” on the range.