By Jim Dickson | Contributing Editor

America’s greatest expert on automatic firearm mechanisms was the late Colonel George Chinn who put that knowledge down in his multi-volume work “The Machinegun.”

The Colonel said that as long as nitrocellulose is our propellant all possible gun mechanisms have been tried and all that is left for the gun designer today is to reconfigure existing locking, feeding, etc. mechanisms into new designs. It is therefore no great surprise that a great gun designer perfected the semi-auto battle rifle many years ago.

The gun designer was Melvin Johnson and his rifle was the M1941 Johnson rifle. It quickly established its superiority over all competitors and drew heavy backing from the NRA and members of Congress who had seen it put through its paces. The gun was the most reliable combat rifle of all time. Melvin Johnson delighted in stuffing a rag in the bore, burying the gun in the sand, and then digging it up, removing the bore plug rag, and commencing to fire.

(Photo credit Edward Johnson)

The Johnson remains unequaled in its ability to throw sand, dirt, and crud out of its action while unfailingly delivering the fire downrange. Unlike most rifles the powder fouling stayed almost entirely in the bore leaving the action clean. The rifle was highly accurate as it was all metal on metal for the barrel which was shrouded in a ventilated heat shield and had a machinegun’s quick change barrel feature. This is one gun that will not burn your fingers or set its stock on fire under prolonged rapid fire. This also came in quite handy for cleaning as you could remove the barrel and pour hot soapy water down the bore to deal with the corrosive primers of the day without ever having a drop of water near the mechanism.

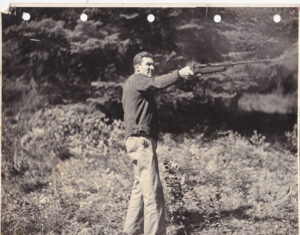

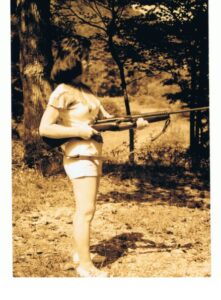

Its recoil operated action had no gas system to corrode or foul and it soaked up almost all of the felt recoil making this a very pleasant .30-06 to shoot. It hangs rock steady on target for aimed fire yet it is lively like a fine shotgun in the hands. This was amply demonstrated by shooting waterfowl on the wing with it. It works splendidly for the instinct shooter. I have killed a deer in mid-leap with a M1941 Johnson with one shot without using sights. There was no time for even a flash sight picture and only instinct shooting could bring that one down.

One of the biggest fears of men in combat is being caught reloading an empty rifle by an onrushing enemy. This is when a lot of men die and everyone knows it. The Johnson has a rotary magazine that can be loaded and also topped off with standard 5-shot stripper clips while it is being fired so theoretically you never have to run out of ammo on the battlefield. A lot of this depends on how focused the shooter is but in practice it worked out quite well and caused a lot of men to really love this gun. The action was not finicky about its ammo handling anything up to 75,000 PSI chamber pressure with aplomb while happily digesting whatever lesser calibers and loads it was fed. Prewar commercial Johnsons often came with a 30-06 and a .35 Whelen barrel and the barrel was all that had to be changed. The mechanism could care less working equally reliably with both.

My own M1941 has its original 30-06 barrel, a 7MM Mauser barrel, and a .35 Whelen barrel set up for the 310 grain bullets of the .350 Rigby as well as the 225-grain bullets of the .350 Rigby magnum and the cartridges are loaded to the Rigby’s velocity. The rifle works perfectly with all of these. The rotary magazine is not particular about cartridge length so the gun will function with a lot more different calibers. To this day there has not been a single gun that can match the M1941 Johnson rifle’s performance much less surpass it. When you are at the top of the mountain all roads are downhill and the Johnson is at the top.

For this test I had 580 rounds of ammunition consisting of 40 rounds of 168-grain FMJ BT Russian Barnaul ammo, and 200 rounds of Black Hills 150-grain GMX soft point ammo. This is a lead free monolithic bullet made from a copper/zinc alloy with a plastic expander tip to insure that it expands up to 1.5 times its original diameter while retaining 95% or more of its original weight.

I also had 80 rounds of Hornady 180-grain SP, the old reliable lead point soft point suitable for any North American game. 80 rounds of Hornady American Whitetail 180-grain SP, 100 rounds of Privi Partizan Rifle Line 150-grain FMJ and 80 rounds of their traditional lead nose soft point ammo. Prvi Partizan is an old respected name among European ammunition makers that deserves to be better known in the U.S. for their high quality ammunition.

The rifle proved able to deliver groups under one minute of angle.

If you believe the old fable that says “Build a better mousetrap and the world will beat a path to your door” the story of the Johnson rifles quest for adoption by the U.S. Army will disillusion you fast. Army Ordnance at the time was a tight little clique with no room for outsiders. They had been tasked with developing a suitable semi-auto rifle for the military but had been unable to do so.

Finally, they brought on board a Canadian, John Garand, and even though his rifle failed to meet the specifications laid out for it they had pushed it through for adoption. During its test trials Ordnance kept substituting new guns as fast as a problem occurred. The new M1 Garand would not work for long with the high powered .30-06 M1 ammo developed for machinegun use in WW1 and subsequently adopted for all .30-06 guns. Ordnance was forced to revert to the original weaker .30-06 load and they attempted to disguise this move backwards by redesignating it the .30-06 M2. When the M2 armor piercing round came out and proved so effective against Japanese coconut log field fortifications that the push was on to have it made the standard .30-06 round Ordnance was faced with the problem that the M1 Garand was not holding up under prolonged firing of this round either. Today some ammo is loaded and sold as “Safe for M1 Garands” by the makers to differentiate it from the hotter 30-06 loads on the market.

If the standard M1905 bayonet with its 16-inch blade was attached to the M1 Garand prolonged firing would warp the gas cylinder and cause jams. This resulted in the bayonet’s length being shortened to 10 inches and finally a bayonet version of the lighter 7-inch blade M3 trench knife was adopted because of this problem.

Accuracy wise the average M1 Garand will shoot 2 to 3 inch groups at 100 yards but this accuracy will decline with repeated cleaning. Unlike the Johnson the M1 has to be cleaned from the muzzle and there is the inevitable damage to the ends of the rifling from the cleaning rod over time. Some ordnance depots kept track of how many times their M1’s were cleaned and routinely rebarreled them after so many cleanings.

The M1 Garand does not like sand at all. I have known the splashing through the surf during an amphibious landing to get enough sand in the M1 to stop it functioning. It also requires grease on the operating rod to function. This is a sand and dirt magnet. When monsoon rains washed off all the lubricant in the Pacific theatre of operations in WW2 the M1 Garand would not act as a self-loading rifle and had to be manually operated. It’s gas system is very vulnerable to corrosion from the corrosive primers of the day and I have seen a man stomp on the operating rod’s cocking handle trying unsuccessfully to move it back when just a little rust got in the wrong place in the Garand’s gas system.

The 8-shot cartridge clip of the Garand is ejected with a loud ping when the last shot is fired. In close quarter combat in the Pacific that sometimes could get you killed. One outfit in that spot took to stationing a man with a Thompson SMG hidden beside a man with a Garand. When the ping was heard and enemy soldiers rushed the Garand user the Tommy gun mowed them down. During sustained rapidfire the M1 Garand will eventually set its upper hand guard on fire from the heat of the barrel. This is the last thing you want to have to deal with during a sustained human wave attack.

The first models of the Johnson use BAR magazines so Ordnance simply had their men load the cartridges in backwards permanently destroying the feed lips. Melvin Johnson caught that and demanded new magazines but was refused. The jams from the destroyed magazines were counted as jams by his gun. Johnson then came out with his rotary magazine that was immune to that problem and could also be topped off with additional cartridges while firing.

The M1 Garand’s action does nothing to soften recoil and the Army’s own recoil figures for it show that it has the same recoil as a bolt action rifle of the same weight. The Johnson’s action absorbs most of the recoil making it very pleasant to shoot. Army Ordnance brazenly lied claiming the Johnson kicked so hard it would break the soldier’s shoulders. My 5 foot two 105-pound wife Betty never even noticed the Johnson’s recoil and she could easily break clay pigeons in the air with it.

Ordnance claimed the Johnson jammed yet an ordnance tester I used to know said it was the only rifle Army Ordnance could never make jam.

Ordnance complained of the unsupported barrel section. Melvin Johnson stood on the unsupported forward part of the barrel with no problem. Today unsupported barrel lengths such as on the M14 are common.

They claimed the rotary magazines were vulnerable to denting but the combat troops didn’t experience that being a problem.

When WW2 began they used that as an excuse to stop any talk of changing the standard military rifle. It should be noted that Germany kept bringing out new and improved models all through the war.

The Johnson was easier, quicker, and cheaper to produce than the M1 and this would have helped immeasurably in WW2 where many American troops had to use bolt action rifles because there were not enough semi-auto rifles to equip all the combat troops.

The Dutch bought a quantity of M1941 Johnson rifles and when Holland fell most of these ended up in Marine Corps and OSS hands where they were well appreciated. Unfortunately, that marked the end of the production of the greatest semi-auto rifle ever made.