By Mike Nesbitt | Contributing Editor

Among the Sharps cartridges which I shoot these days, the .44/77 is easily my favorite.

My reason for liking it is based more on history rather than performance. The .44/77 was one of the cartridges Sharps made available in their Model 1869 Sporting Rifle, along with the .40/70 Sharps and the .50/70 Government. The .44/77 caught on, so to speak, and became the most popular cartridge in the Sharps Models of 1869 and the 1874, until the .45/70 “took over” in 1876. I like the .44/77 today mainly to carry on the tradition.

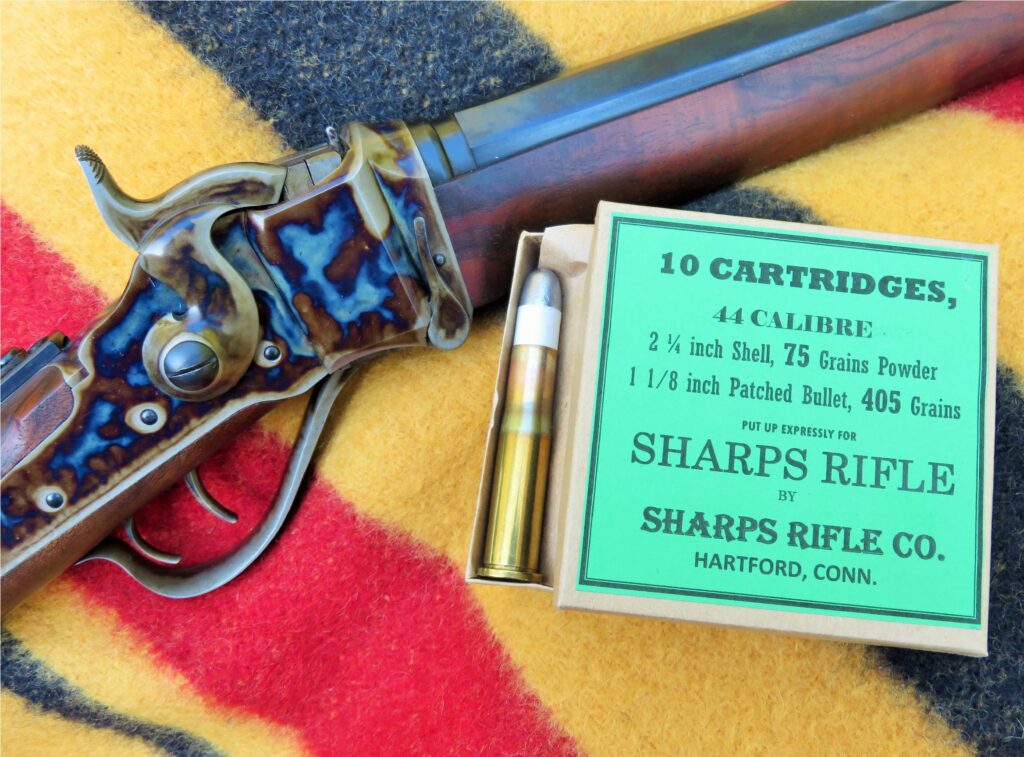

The official name for this cartridge is actually the .44-2 ¼”, identifying it as a .44 caliber bottlenecked cartridge with the case length of 2 ¼ inches. Before 1875 the standard Sharps loading for this cartridge used a 380 grain paper patched bullet over 70 grains of black powder, so it could be called the .44/70 Sharps. Then after 1875 Sharps made a chance to their standard loading for this round, increasing the bullet weight to 405 grains and increasing the powder charge to 75 grains. There were other loadings in this 2 ¼” case by other manufacturers and the use of 77 grains of powder was actually started by Remington, under a 400 grain bullet. That gave this cartridge its most remembered name but it was still the .44-2 ¼” Sharps.

The development of the .44/77 Sharps cartridge has never been made completely clear, in my humblest opinion, and I’d like to plant some seeds of thought in your minds about when and where this notable cartridge was developed. Please bear in mind that I am really guessing at some of this but my few guesses are made, I hope you will agree, with a rather fair foundation.

First of all, as Frank Sellers said in his book Sharps Firearms, the .44/77 was based on a Remington cartridge. Too many of us have believed that Remington had the .44/77 first and that Sharps simply adopted it as a chambering in their Sporting rifle of 1869. Remington did have their .43 Spanish, which was developed at almost the same time, so let me ask, why would Remington introduce such similar cartridges firing bullets only .007” larger than the .43 when such a move would not be worth the tooling to do it?

My assumption is this; Sharps borrowed the case from the .43 Spanish (maybe from the .42 Berdan, which was developed by Union Metallic Cartridge Co. in 1868) but adapted it to the .44 caliber barrels they had already been making for their .44 percussion sporting rifles. Sharps had been marketing .44 caliber sporting rifle for almost twenty years by that time. They made their own barrels and only needed a .44 caliber cartridge to put a new center-fire rifle/cartridge combination on the marker. I have a friend who has one or more of the old Sharps .44 caliber percussion rifles, such as the Model 1853 Sporting Rifle, known as the “slant breech Sharps,” and he verifies that the .44/77 Sharps used the same bore and groove diameter barrels. It would have been rather natural to use existing tooling for those barrels.

Also worthy of possible note is that Ballard bought their target barrels in .44 and .45 calibers from Sharps. Sharps barrels did have a fine reputation.

Sharps always referred to this cartridge as the .44-2 ¼”, as it was usually stamped on the barrels of the Sharps rifles, loading it with either 70 or 75 grains of powder under 380 and 405 grain bullets. According to Roy Marcot in his excellent book about Remington Rolling Block Sporting and Target Rifles, the earliest mention of the .44/77 by Remington did not take place until the latter part of 1872, about the time that production of their #1 Sporting Rifle really got under way. That in an advertisement in Army and Navy Journal when Remington was highlighting their new version of their #1 rolling block, the long range Creedmoor model.

This all strongly suggests that the .44-2 ¼” cartridge was originally made and developed by Sharps, either from the .43 Spanish which was also developed in 1869 by UMC or, like the .43 Spanish, developed from the .42 Berdan which also used 77 grains of powder. Sharps and Colonel Berdan were certainly not strangers. Sometime later Remington adopted the .44-2 ¼” as a chambering for their Sporting Rifles and gave it their own designation, the .44/77. Remington also continued to chamber the .44/77 in their rolling block rifles after Sharps had discontinued it in 1876 as a standard chambering.

And loadings for the .44-2 ¼” case continued to be changed. The famous Creedmoor shooting matches were won with Sharps and rolling block rifles using .44/90 ammunition. Those .44/90s, however, still used the same 2-1/4” case which became known as the .44/90 Regular. It used bullets up to 600 grains in weight, perhaps generally a 470 grain bullet, over the 90 grains of compressed powder. That was no lubrication under the paper patched bullets in that load, and when used in competition the rifle’s barrels were cleaned after each shot. The .44/90 Regular loads were still being shown in the Winchester catalog of 1916.

On the sporting side, rather than in target competition, the .44/77 Sharps easily won the hearts of several riflemen. In the West it was a standard on the buffalo hunts, being more prominent in numbers than the .44/90 or the big .50/90 rifles.

To bring things up to date, shooting a .44/77 today does require some special order tools for reloading. While reloading dies must be ordered, getting a bullet mold for the .446” diameter bullets is fairly easy. They are made by Accurate Molds, Steve Brooks, and KAL in Canada. The highly favored Jamison brass is no longer made but reformed cases are available from Buffalo Arms Company and newly made cases are being produced by Roberson Cartridge Company. Once those dies, bullet molds, and brass cases are collected, all you need is a .44/77 rifle for good shooting.

My hunting days might be behind me but even so, I do think about hunting deer or antelope with my .44/77 by C. Sharps Arms. The only thing stopping me, is me… But I do use the .44/77 on the “steel buffalo” at the Matthew Quigley Long Range Match in Montana and I’ve used my heavy .44/77 (Hefty Hannah) on the buffalo silhouettes with the Great Basin Sharpshooters down by Bend, Oregon with targets out to 1,000 yards. Getting a good hit at 1,000 yards with an iron sighted black powder rifle certainly gives the sound of the bullet hitting the steel targets the “ring” of success.