By Dave Workman | Editor-in-Chief

Having seen and held antique handguns with genuine ivory grips, and having once many years ago fired a revolver so equipped, the appeal of ivory as a grip material has intrigued me for decades.

The late Elmer Keith’s revolvers typically had ivory grips, and they contrast handsomely with the blue steel of his N-frame Smith & Wesson magnum sixguns.

Alas, genuine ivory is off the table for my revolver grips, but there have been substitutes that caught my eye. More than three decades have passed since purchasing a set of un-marked “bonded ivory” grips for a Model 57 Smith & Wesson double-action revolver in .41 Magnum I had recently purchased. This stuff, according to the guy who sold them, was made from a mix of real ivory dust from the days when it was still legal to import ivory for handgun grips, knife handles, piano keys and chess pieces, and some type of resin or polymer material.

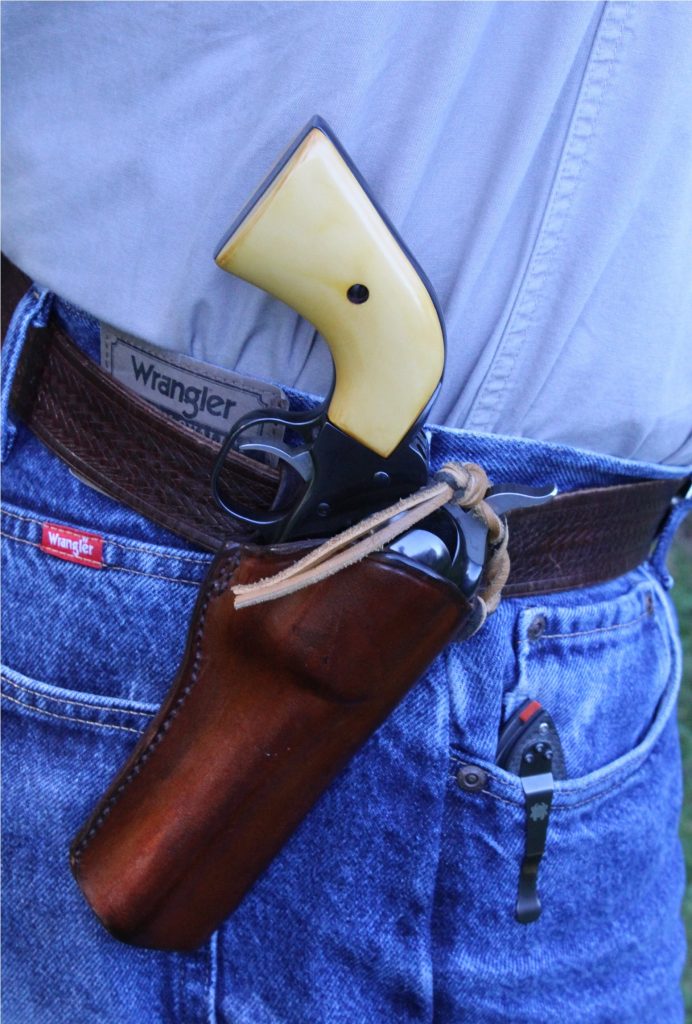

I’m not sure that was true, but over the years, the grips have developed a patina, especially on the right side. That’s the surface that my gun hand contacts, and it has seen plenty of perspiration over the decades. It’s also the surface more exposed to sunlight because the revolver rides on my right side.

For aftermarket grips, there is still real stag and elk antler, and some handsome substitutes, and I’ve tried them all to complete satisfaction.

Recently, this writer had a chance to examine a set of “Magna-Tusk Aged Ivory” grips from Arizona Custom Grips, and it is nearly impossible to tell them from the genuine ivory grips found on old Peacemakers and Colt percussion revolvers.

TGM reached out to Davis Rand, owner of the Mesa, Arizona-based grip company, and learned the following:

“Magna-Tusk™ Ivory and Stag grips are manufactured out of our high-grade, high density ivory material designed from the beginning as a premium, high-strength grip material,” he said via email.

In a subsequent telephone conversation, Rand noted that Magna-Tusk grips are “just like real ivory” in that no two are exactly alike.

“The reason we developed Magna-Tusk,” he recalled, “we used to sell bonded ivory like everybody else—imitation ivory.”

But he experienced less-than-satisfactory results with that material, and set about finding something better. What developed is something beyond typical “imitation ivory” and they call it “Magna-Tusk.” It is described, in Arizona Custom Grips literature, as being “capable of withstanding the heaviest recoil and impact, and is the toughest alternative grip material available today, while still retaining the pristine look of real ivory or stag. It is rock-solid, stable, and water, chemical, and oil resistant. It is flame and heat resistant, and is entirely void-free, with over 10x the strength, durability, and impact resistance of alternative materials.”

Rand said he put some Magna-Tusk on an anvil and struck it with a hammer “a couple of times” before he was able to crack it.

A set of the Aged Ivory grips obtained for review looks to meet all of those claims. On top of that, the coloration was remarkable because, just like genuine old ivory, it seemed to change color depending upon the light conditions, which is the kind of optical illusion one often sees with genuine ivory that has yellowed. Under bright light conditions, it appears to be brilliant yellow, while under different light, the stuff seems to pale.

Something else important to me is that these grips are flat on the bottom, not beveled as one often finds on after-market grips for single-action sixguns. Bevels are an annoying design feature that has never made sense to me.

Arizona Custom Grips are crafted using CNC equipment, and the Magna-Tusk grips we had were spot-on in terms of grip-to-metal fit. The finish is smooth and comfortable, and the grips allowed our Ruger New Vaquero in .45 Colt to rock back like it’s supposed to under full recoil.

Magna-Tusk is available without the “aged” ivory finish, as well, and with that finish, it looks just slightly off-white, much like the ivory panels on Keith’s various S&W revolvers, images of which can be found easily online.

But for what some folks might call the “John Wayne finish” as seen on his sixgun during his later films including “El Dorado,” “True Grit” and “The Cowboys,” it’s the aged ivory that will certainly get their attention. The grips on Wayne’s gun were reportedly made from something called Catalin, not genuine ivory, and one account had him soaking the panels in tea to add color.

The Magna-Tusk process is a bit more scientific.

According to Rand, “The patina on our aged ivory Magna-Tusk grips is a real patina, using concentrated U.V. light, which is exactly what ages real ivory and bone. That is how we get it so authentic. As part of the process, we use a developer (put on the grips) as an aid to control the absorption of U.V. Some of it gets on the back of the grips, which is what you see on the backside. It causes the U.V. to be absorbed at a different rate.”

We checked the inside surface of the grips and sure enough, this “developer” formula did leave some small streaks. Nobody’s going to see them, anyway, once the grips are installed.

In this writer’s opinion, Magna-Tusk has other materials beat in terms of color and durability, though we didn’t whack them with a hammer!

As it turns out, Rand is a fan of the late Mr. Keith—the legendary cowboy-turned-big game guide, author and renowned hunter, and the father of long-range handgunning—and he understands the importance of grip shape and mass. We chatted about that at some length and agreed that for handguns firing full-house loads, slightly wider grip surfaces are preferable to spread the impact of recoil across a wider area of the palm. Today, many folks involved in Cowboy Action shooting have gravitated toward slightly thinner grip panels, and since they typically shoot lighter competition loads, that works just fine.

Presently, Arizona Custom advertises the Magna-Tusk grips on eBay, but Rand said the company will have a website up soon at “azcustomgrips.com.”

These grips are moderately priced and look tough enough to hold up through years of service.