By Art Merrill |Reloading Editor

Anything new is presumably an improvement over something already available for a particular task.

When it comes to smokeless powders for metallic cartridge reloading, it seems hardly possible there would be room for anything new. But there is.

According to Hodgdon’s 2020 list of powder relative burn rates, we’ve got 163 powders from which we can choose. These are tailored specifically for pistol and rifle cartridges, and then those categories are each refined for best use within a specific range of case volume and even bullet weight. When you can’t split these hairs any finer, what do you do next to get a handloader reaching for his wallet?

Smooth, fast

In 2018 Hodgdon released a new IMR powder they call “Target,” for use in pistol cartridges in the 9mm/.38 Special/.45 ACP arena. So, why do we need another powder in that class when there are already plenty of proven choices?

“IMR Target is a very consistent, fine grained, small flake powder that meters superbly,” Chris Hodgdon said when I asked him. “Compared to Brand X, you’ll find it flows beautifully and is very clean burning.”

Powder that flows smoothly through a measure without hanging up is an important characteristic for ensuring consistent case-to-case charges, which is, of course, important to precision shooting. But even for informal target shooting or plinking, we want our bullets to go where we’re aiming, and for that we need those consistent charges.

Powder hang-up in a powder measure can occur with extruded rifle powders, as well as with pistol powders, which are typically flake type, like Unique or W231; these latter types especially can stick to a measure’s rotor or clump together. That stickiness is why we see “knockers” on some, especially older powder measures; lifting and dropping the knocker after charging a case encourages any sticking powder granules to let go and drop into the case or pan after their brethren.

Pistol shooting for competition (or a day’s plinking pleasure with friends) is all about volume, reloading mass quantities of ammo at a go, and mass quantities means using a progressive reloading press. At this level of handloading, we don’t weigh every charge, we adjust the powder measure to the charge weight we want and let it do its thing automatically with every pull of the handle.

With progressive reloaders, then, smooth flow through a powder measure is a requirement. If the powder clumps or sticks to the measure, any particular case may have too little powder, too much powder, or have our Goldilocks “just right” charge; either way, it is not conducive to keeping bullet holes close together. Before we blame the powder, however, let’s look at the powder measure.

Cylinders, flakes and spheres

Many old timers “seasoned” a new powder measure by throwing a full reservoir of powder charges through it. The belief is that the some of the powder granules’ graphite coating wears off to deposit on the measure’s interior and act as a dry lubricant to prevent powder from sticking. To help prevent powder clumping in the measure, many older powder measures – and, for example, today’s Redding powder measures – feature a baffle at the bottom of the reservoir. Powder that may have clumped due to being compressed by the powder column above it “sifts” through the baffle to fall freely into cases.

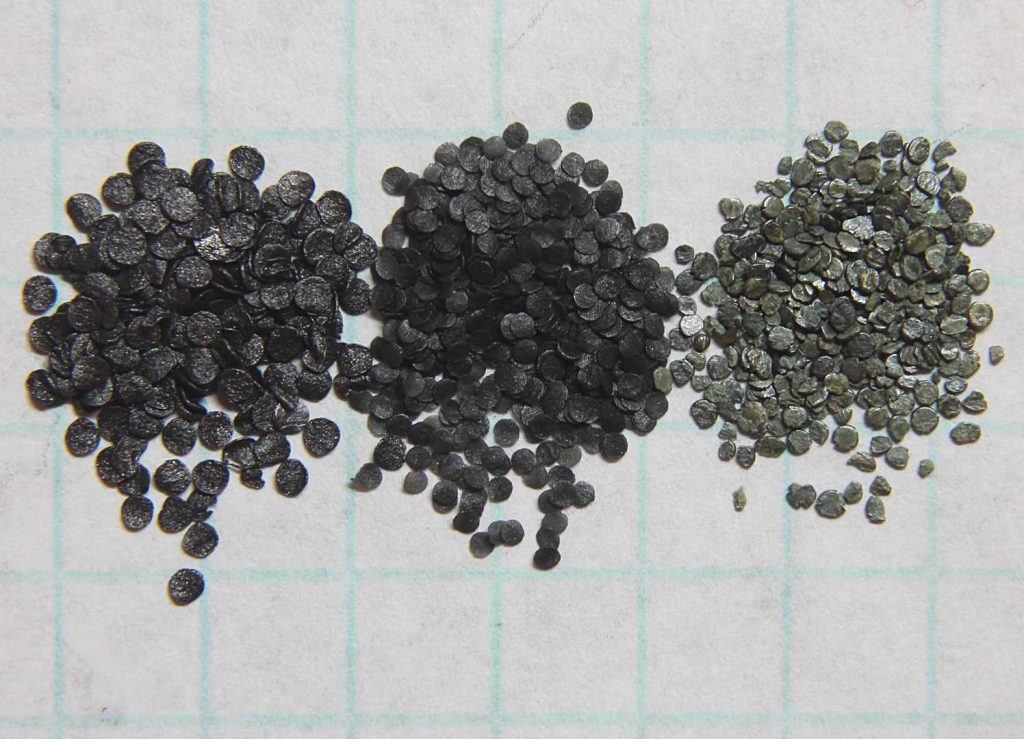

But a powder’s physical characteristics are the number one determinant to its metering behaviors. Extruded powders can be cut by a powder measure’s rotor or bridge across a narrow funnel or rifle case neck. Granules with flat or rough surfaces may tend to cling together and form clumps; the graphite coating helps to assure a smooth surface. Rounding the edges of the granules also helps prevent clumping or sticking. Spheres have no edges, so spherical powders flow much better than flake powders. Smooth flow, again, equates to consistent charges.

Powder granules have their extruded (cylindrical), flake (flat) or ball (spherical) shapes because each contributes to that powders’ desired performance. Thin, flat flake powders burn rapidly compared to extruded or ball powders, and so find their home in pistol cartridges. Rifle cases, with their larger volume, perform better with slower-burning extruded powders. Ball powders fall in-between and may be specified for either rifle or pistol cartridges.

IMR Target offers the benefit of a ball powder’s smooth metering in a flake format, and a consistent case-to-case charge is a powder’s first step in making an accurate cartridge. IMR Target’s second benefit is in burning cleaner than flake powders because, of course, a dirty bore can adversely affect accuracy – plus it’s more of an after-shooting chore to clean up.

Testing claims

Can IMR Target really outperform Brand X? Testing shot groups to a high level of confidence requires a comparative analysis of many scores of loads, the more the better. But let’s take a less onerous approach.

I adjusted an RCBS Uniflow powder measure to throw 3.6 grains of IMR Target, and then threw and weighed 50 charges on an electronic scale accurate to +/- 0.1 grain. Of those, 44 charges weighed 3.5 to 3.7 grains; taking into account the scale’s plus-or-minus tolerance, that’s on the money. Six of the charges weighed 3.4 grains. That tenth of a grain difference may be due to several factors – powder, scale, powder measure, my technique – but in the larger scheme of reloading pistol cartridges and the manner in which we usually shoot them, it is inconsequential and rates as top-notch consistency. I tapped the measure over a piece of white paper after each case charging to show no powder stuck to the measure.

Next, I loaded 50 rounds of .38 Special into R-P cases and fired them through a S&W Model 10 M&P revolver. On Hodgdon’s chart of smokeless powder comparative burn rates, IMR Target is about on-par with Bullseye and 700-X. Hodgdon’s online Load Center https://www.hodgdonreloading.com/ includes some loads for IMR Target, but not for the cast 138-grain LSWC bullets I had on hand, so I ballparked that 3.6 grains of IMR Target based on Hogdon’s 130-grain and 140-grain lead bullet loads. Winchester Small Pistol primers started the show.

Firing five 10-shot strings over a chronograph resulted in an average velocity of 750 fps, an extreme spread (ES) of 50.62 fps and a standard deviation (SD) of 16.48. Both ES and SD quantify differences in bullet velocities, but while ES is the average between the slowest and the fastest bullet, SD takes into account the variance of all the individual shot velocities in the string, so it’s more precise. The SD is our best indicator of consistency – the lower the number, the more consistent the shot-to-shot performance, and that equates to precision.

The SD recorded by the IMR Target load is very good, and one 10-shot string turned in an SD of only 11.04. We might see lower SDs with carefully constructed precision rifle cartridge handloads, but for a small quantity of powder that takes up little volume in .38 Special cases that had no match grade prep to them, it appears that IMR Target lives up to its namesake.

Clean burning? That’s harder to judge objectively, but an after-range session with the cleaning gear showed IMR Target doesn’t seem to leave as much powder residue as some other pistol powders we use, so I’d give the claim to clean burning a thumbs-up.

IMR Target indeed appears to be an improvement in pistol powder; next time you feel the need to experiment with an upgrade, pick up a pound and try it for yourself.