By Art Merrill | Reloading Editor

Some years ago, 300 cast lead .38 caliber wadcutter bullets came into my hands, and they’ve rested on the shelf until now.

I recently purchased a used Ruger Single Six in .357 Magnum with the idea that perhaps for the spring javelina season I’ll swap out the muzzleloading rifle for the revolver. That, of course, requires load development for the revolver, which naturally (for a target shooter) leads to the thought of wadcutter bullets. Hunting aside, how well might the Ruger shoot with wadcutters? Here, I thought, is a good opportunity to show new handloaders one facet of moving from “Beginner” toward “Advanced” – safely and effectively loading with “mystery” bullets of unknown manufacture.

Four steps

My four steps for reloading bullets of unknown manufacture – say, bullets in coffee cans or plastic sandwich bags bought at a yard sale or swap meet – are simple, important and based on the premise of, “Don’t assume anything.”

- ID the bullet type. We’ll need this info when we look at load data. Also, a bullet is best used for its intended purpose; jacketed hollow points (JHPs) are wasted on paper targets, and driving cast or swaged round nose lead (RNL) bullets at too-high velocity causes barrel leading and inaccuracy. Bullets have other refinements as well, but you get the point.

- Measure the bullet diameter. For example, there’s only two thousandths (.002) inch difference between a .355” 9mm/380 ACP bullet and .357” bullets for the 38 Special/357 Magnum, indistinguishable to the naked eye, but we’ll run into considerable frustration and possible hazard if we use the wrong bullet in the wrong firearm.

- Weigh. We can’t even begin to make up safe loads if we don’t know the bullet’s weight, as this feature, like bullet diameter, is information integral to all load data.

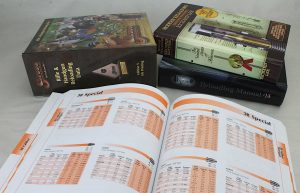

- Cross reference. Once we have the bullet type, diameter and weight, we check several different load data sources for loads for that bullet. Disparity among loading manuals is routine, for reasons we’ve covered in the past, and cross referencing will give us some logical parameters within which we can safely work.

Steps 1, 2, 3

Full wadcutters and the 38 Special are an iconic combination in target shooting.

In a past article about the lead semiwadcutter bullet (LSWC) http://www.thegunmag.com/jack-of-all-trades-the-lswc/ I touched on the full wadcutter (WC) bullet which, subsequent to some minor evolution since about 1900, is today basically an un-pointed lead cylinder. Lacking any hint of genuine aerodynamic shape, the full WC is a comparatively short-range affair, but within its limitations of range and velocity it has earned a reputation for accuracy. Its impetus for invention was that the design punches clean holes in paper targets for more accurate scoring when shots land adjacent to target scoring rings. Our 300 WC bullets here, then, are for short range target shooting at comparatively low velocity.

The 300 bullets came carefully packed upright in three old, c. 1960s Speer bullet boxes labelled, “38 CALIBER 148 GRAIN WAD CUTTER.” I thought at first glance they might be the genuine factory article, but the casting sprue cuts on the bullet bases decry the “SWAGED LEAD” printed on the box, and the lack of the bullet crimping groove also depicted on the box, as well as the soft bullet lubricant (factories typically use a harder lube), indicates these are some anonymous person’s cast lead bullets. It’s fairly common for bullet casters and handloaders to utilize empty factory labelled boxes to store home cast bullets and handloads, reemphasizing the rule about not assuming anything.

Caliper measurement of a handful of bullets shows a consistent .3575” to .3580” bullet diameter, so these are .38 caliber. On a digital scale, weights of 100 bullets ranged from 151.9 grains to 154.2 grains, averaging at 153.0 grains. A two-grain difference among bullets intended for precision target shooting is a bit of a spread; ideally, all bullets should weigh the same or at least within two tenths of a grain of each other, but for this non-precision exercise I gleaned 32 bullets weighing a close-enough 152 to 152.9 grains.

Special or Magnum?

Cross referencing load data permits us to determine a safe starting load for mystery bullets.

Decision time: do we use .38 Special or .357 Magnum cases? While the raison de e’tre for the .357 Magnum is to outperform the .38 Special, we’ve already noted we’re not after high velocity here. But theoretically, in starting the bullet a wee bit closer to the forcing cone and minimizing how far the bullet must “jump” to reach the rifling, accuracy may be improved by using the longer .357 Magnum case. On the other hand, using the .38 Special case decreases the volume of empty space inside the case and theoretically may improve accuracy by providing more consistent shot-to-shot pressures with those tiny charges of pistol powder.

Here, then, is an opportunity for careful experiment and comparison of theories. Or, we can simply note that pretty much every competition target revolver shooter chooses the .38 Special over the .357 Magnum, and follow suit. Consistency is the mother of smaller groups on the target, so for the same reason we weigh bullets, I measured 38 Special cases and chose 32 that fell between 1.147” and 1.148” in length.

Step 4 and choose

In looking up load data, we find nothing for 153 grain .38 Special full wadcutters because the industry standard for such bullets is 148 grains, though Lyman lists a 150 grain WC thrown from their mold #358091, and a 155 grainer from mold #358156, both using Linotype. The Lee, Hornady and Speer manuals all list 148 grain WCs with Winchester W231 powder, and Lyman lists it with both their WCs; because I have plenty on hand and have had good experience with it in the past, let’s go with W231. The manuals list starting and maximum loads of W231 thusly:

Manual Start gr Max gr Velocity fps

Hornady 3.8 4.4 800 – 900

Lee 3.4 4.0 869 – 956

Speer 3.0 3.3 749 – 804

Lyman 3.7 4.2 872 – 942 (150gr)

Lyman 3.5 4.7 680 – 885 (155gr)

There are other methods for figuring a safe starting charge for rifle cartridges, but because pistol cartridges work with such small powder charges (note that, except for the 155 grain Lyman bullet, only 0.3 to 0.6 grains separate starting charges from maximum charges here), and as our mystery bullets are about four percent heavier than 148 grains, let’s go with the most conservative starting charge, Speer’s, of 3.0 grains of W231. Velocities of the Speer data are lower than the others, and as we don’t know how hard our mystery bullets are (Linotype is harder than pure lead), we can avoid possible early leading problems by starting slow. Small Pistol primers are proper for 38 Special, of course.

Two tools critical to identifying mystery bullets: the scale and caliper.

These, then, are the steps for safely dealing with reloading unknown bullets: ID the type, measure, weigh and cross reference. This is a good place to note once again that bullet manufacturers publish load data intended only for their own bullets, and they do not warrant that the data is safe for any other maker’s bullet of the same weight and caliber. That is, for example, Sierra does not intend load data for their own 165 grain .30 caliber GameKing bullet be used with 165 grain .30 caliber bullets from, say, Hornady or Nosler. This is because bullet makers work up load data only for their own bullets, of course, and there’s more than just a bullet’s weight that affects pressure.

The thickness or composition of a bullet’s jacket or the length of its bearing surface, as examples, also affect gas pressure, and these will differ among different makers’ bullets of the same weight and caliber. A possible result is that a powder charge weight that is safe for one maker’s bullet may not be so with a different maker’s bullet of the same weight and caliber, especially as we approach maximum loads.

This doesn’t mean experimenting with bullets of unknown manufacture is unsafe. Open a Lyman or Lee load data manual, and we find that neither specifies bullets from any manufacturer. Under .30-06 loads for 168 grain bullets, Lee lists, “168 grain jacketed bullet,” and Lyman is only slightly more specific with, “168gr Jacketed HPBT.” Safe experimenting with bullets of unknown manufacture calls for starting with minimum loads, using a chronograph and watching carefully for early signs of excessive pressure – preceded by the four steps for dealing with mystery bullets.