By Art Merrill | Contributing Editor

Dueling with wax bullets was a short-lived pursuit at the turn of the 20th century. (Photo courtesy rarehistoricalphotos.com)

Firearms are pretty serious business, their original basis being the intent to inflict terminal harm on an enemy. Today we see them emphasized in America as tools for the defense of self, family and Republic against persons of ill will. They do have less grim roles, such as in plinking, recreational hunting and competition, but they are no less lethal in filling those roles.

But it doesn’t always have to be that way. If you’re a Sherlock Holmes fan, perhaps you recall reading about the quirky detective shooting a revolver for recreation in his parlor at 221B Baker Street (though Dr. Watson offers no insight into what the neighbors in 221A or 221C thought of the practice). Circumstances permitting, we handloaders, too, can enjoy relaxing with some indoor plinking at home if we eschew the powder and allow the primer alone to send a bullet of paraffin wax to a target affixed to a cardboard trap.

Wax market

The concept of wax bullets goes back to at least the early 1900s, and it may be older than that. A demonstration at the 1908 London Summer Olympics featured a new sport of dueling with percussion muzzleloader pistols firing wax balls. Competitors wore face protection and heavy canvas overcoats; a guard, similar to that found on some swords and mounted in front of the trigger guard, protected the duelists’ hands. Obviously, the sport never caught on.

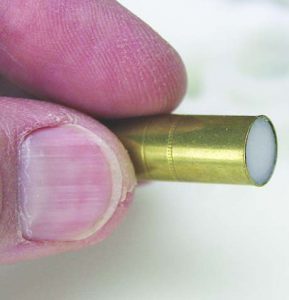

Use the cartridge case as a ‘cookie cutter’ to mold a bullet from the semi-hard wax.

The concept returned in the late 1950s with the advent of popular “fast draw” shooting in the manner of Hollywood western movies. The 1962 Handloader’s Digest has a page describing and pricing tools for reloading wax bullets, as well as cartridge cases modified with enlarged primer flash holes and bullets made of mixed wax and plastic compounds. Capitalism carries the concept forward in providing today’s fast draw and cowboy action shooters a competitive edge (or perhaps more armchair time) with similar offerings of tools, components, reusable bullets, cases modified to accept shotgun primers, and special cleaning tools and solvents intended specifically for dealing with wax.

But for the non-competitor, no special tools, cases or wax formula is really needed, so there’s nothing to buy other than plain paraffin wax, which today is still available at many grocery, hardware and art supply stores. The bullet mold is in the cartridge case itself. The only case prep is to enlarge the flash hole a bit with a drill, but even that isn’t entirely necessary, and beveling the case mouth is also optional. A primer alone drives the wax bullet – a powder charge is not only unneeded, it is undesirable, as its high temperature would vaporize the wax bullet.

Wax cleanup presents no special problem. Using a brush and solvent as you normally do works fine, and it’s less time-consuming because there is no powder residue to worry about. The wax bullet adventure is pretty low-tech, and the amusement is worth the minimal effort.

Making wax bullets

Note that primer-driven wax bullet “loads” are unlikely to cycle semiauto actions, so this exercise is limited to manually operated firearms such as revolvers, single shots, and bolt and lever guns. Here, let’s work with the ubiquitous .38 Special, starting with case prep. Experimenters long ago reported that enlarging primer flash holes slightly will help prevent primers from backing out upon firing wax bullets and possibly interfering with revolver cylinder rotation. Honestly, I’ve never suffered that problem shooting wax bullets; you might save yourself the trouble and try unmodified cases first, and then drill the flash holes if you experience the problem. You will use the case itself as a kind of cookie cutter to make and seat the wax bullet, so beveling the case mouth may cut a cleaner bullet. Again, your call!

Enlarging flash holes with a 3/32 drill and chamfering case mouths is optional.

With a handful of cases ready for loading, it’s time to melt the wax. Paraffin wax sells in small blocks; because it melts at low temperature, it’s easy to work with. There are any number of methods to melt the wax; one is to place the block in an old pie pan or small, disposable aluminum pan in an oven set just warm enough to melt the wax block. Many ovens won’t heat below 170 degrees; if you’ve got one of those, heat the oven to maybe 200 degrees, turn it off, and then place the pan of wax in the oven. Wax, of course is somewhat flammable, so care is in order.

After melting, let the wax cool until it is semi-hard, then push the mouth of the empty case into the wax, all the way to the bottom of the pan. You’ll note here that the depth of the wax in the pan determines the length of the wax bullet; bullet length and its effect on accuracy (to be generous with the term here) is an aspect ripe for your experimentation. Give the case a half-twist and pull it out; the wax bullet will stay in the case. If it doesn’t, the wax is too liquid or too hard – you’ll get a feel for it as you work with the wax. Afterward, seat a primer as you normally do.

It’s best to seat the wax bullets before you prime the cases. With a primer already in place, inserting a wax bullet into the case compresses the air inside the case; the compressing air, of course, pushes back and can prevent the wax bullet from seating or seating fully in the case. A protruding wax bullet is an invitation to deformation of the soft wax, smearing wax from the bullet into the chamber(s) or to introducing into the firearm’s bore any grit picked up by the wax. Seating the wax bullet before priming allows the air to escape through the primer flash hole and permit seating flush with the case mouth like a full wadcutter bullet.

Considerations

Paraffin wax, a way to melt it, primers and cases are all you need to load wax bullet cartridges.

This, by the way, is an appropriate use for old primers or other “mystery” primers you don’t wish to rely upon for more serious tasks. If you’ve never fired a solo primer, you may be surprised at the loudness of the report. The sound is not alarmingly loud from outside when fired inside your garage but it is loud enough that hearing protection for the shooter is appropriate. And do note that if you live in a municipality, it’s a pretty good bet there’s an ordinance prohibiting firing even primer-driven wax bullets from a firearm in your garage or basement. In no way do I advocate flaunting the law.

Concerned about airborne lead from the lead styphnate in the primers? A report in the October 2014 Shooting Sports USA magazine concluded that even in a semi-ventilated 8’x8’ room, it would require the inhalation of about 460,000 primer firings to exceed the OSHA limit for lead exposure. The real hazard of airborne lead when shooting indoors comes from hot powder gases vaporizing lead from bullets. Still, with only minimal ventilation, Mr. Safety gives a nod to lead-free primers.

Entertainment factor

So, why bother with wax bullets? If we need an excuse, we might claim a benefit in training, both at the reloading bench and in firearms handling. Frankly, shooting wax bullets is not a pursuit in precision shooting, though at 15 feet shots will stay in the scoring area of FBI low-contrast “Q” targets (depending upon your particular firearm, of course). And shooting at longer distance can serve to demonstrate how rifling twist induces left or right drift into a bullet’s flight, as the wax bullet is clearly visible to the shooter when fired over 50 feet or so.

But really, it’s just the entertainment factor. Especially during those long lulls between investigative adventures into the criminal underworld seeking out your own Professor Moriarty, the loading exercise provides something creative to occupy the curious mind, and there is amusement in uncomplicated indoor shooting in your own parlor. Whether your neighbors might be similarly amused, is for you to take into account.