By Art Merrill | Contributing Editor

History is where you find it. It can be highly visible in, say, a statue in your city park, but there’s also a lot of history tucked away behind the mundane, the everyday things we take for granted. And history isn’t always “old” – it can be as close as yesterday. Our example here is a smokeless powder because here, our subject is handloading.

A 1957 Hodgdon magazine ad included BL-Type-C powder.

More famous for its original cordite “stick” powder, in England the military 303 British cartridge officially changed over to DuPont #16 nitrocellulose powder in 1916. Though unique in form and in its manner of charging–which consisted pretty much of cutting “sticks” of cordite to a set length and dropping them into a case, with a cardboard wad on top – and valued for its stability in the heat of the tropical parts of Britain’s empire, cordite earned a reputation for eroding bores and even for weakening barrels, at least partially due to its relatively high burning temperature. Still, a few nations that used the cartridge continued loading with cordite well into the Cold War. Cordite-loaded cartridges are still around and enjoying some collector status. Those who shoot them out of curiosity sometimes report that they suffer occasional hangfires, but they still usually go, “bang.”

During WWII, manufacture of 303 British ammunition switched to loading with the new-fangled WC 846 spherical or ball powder made specifically for the cartridge. Among its other properties, WC 846 burned cooler than cordite, saving barrels, and charging cases with the smooth flowing ball powder was even easier than with cordite. At war’s end, as with other war materiel, there was a huge surplus of WC 846 and ammunition. Hmm…what to do with it?

From war to shooting sports

“As early as 1947 (the year Grandad Bruce founded Hodgdon), we were aware of a big surplus of .303 British ammunition,” Chris Hodgdon told me in an email exchange. “Bruce purchased the salvaged, demilled powder from Olin Matheson Chemical Company and resold it as Western Ball Type C. Grandad thought this particular powder was cooler burning in his 22-250, so that’s where the ‘C’ part came to be.”

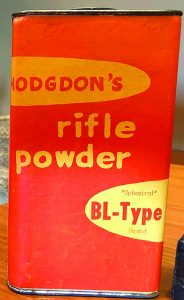

Hodgdon’s first commercial incarnation of milsurp 303 British powder: BL-Type, a then-newfangled spherical powder. (Chris Hodgdon photo)

The “C” part is apparently also due to trademark concerns. Because Olin owned and still owns trademark to “Western” and “Ball” in regards to smokeless powders, Hodgdon changed the powder’s name from Western Ball Type C to “BL Type C” or, “BL-C.” Due to its cooler burn being kind to chamber throats, its smooth metering and its fairly wide application in small to medium size rifle cartridge cases, BL-C quickly gained popularity among handloaders.

“Hundreds, if not thousands of shooters won many precision rifle matches using it through the 1950s and 60s,” Chris said. “It is still highly coveted by those lucky enough to find it.” As an aside, in that statement we find the answer to the oft-asked question, “How long do smokeless powders last before they go bad?”

Hodgdon purchased 80 tons of the surplus powder and started selling BL-C in 1949; by 1961 the 80 tons had diminished by the pound and keg, so Hodgdon replaced the milsurp powder with a newly manufactured version, BL-C (Lot #2). Hodgdon claimed the new version was cleaner-burning than BL-C; burn rate is close to the original BL-C, but BL-C and BL-C (2) are not identical and data between the two are not interchangeable. Since introduction, many handloaders have verbalized the “BL” as “Ball,” as in, “Ball-C Two.”

The new (2)

In burn rate, Hodgdon BL-C (2) is in the same neighborhood as Norma 201, Winchester 748 and Reloader 12. A perusal of a half-dozen reloading manuals, current and a bit older, show BL-C (2) suggested loads for cartridges starting from 17 Fireball, becoming quite popular for the .22s and then petering out at about the 7mm Mauser except for a smattering of .30 caliber loads with light-for-caliber bullets. Interestingly, only one manual, Hornady’s 4th Edition, listed a BL-C (2) load for the 303 British.

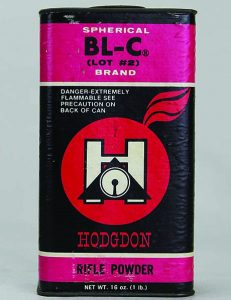

BL-Type was so popular that, when Hodgdon ran out of all eight tons, they commissioned a commercial replacement in the 1960s, Lot #2 of BL-C.

Obviously, the difference between BL-C and BL-C (2), as well as the plethora of powder choices today, has favored BL-C (2) toward smaller cases. This is perhaps borne out by a 1950s BL-C load (Speer) for the 7mm Mashburn Magnum, essentially a necked-down and blown-out, cavernous 300 H&H belted magnum case. The load, 62-gr. under a Speer 130-gr. bullet, if you’re curious, lists a muzzle velocity of 3150fps. That’s the largest cartridge case for which I found a BL-C load.

In general, BL-C (2) loads appear to somewhat trend in this way: in the smallest cases, it shows up under the heavier bullets for that cartridge; as we progress into larger cases, it tends toward loads for the lighter bullets. But that’s not a hard and fast rule. Confining ourselves to just the current Sierra manual (5th Edition), in one exception Sierra lists a 308 Win BL-C(2) load for the 190-gr. bullet – definitely a super heavyweight for that cartridge. Then moving up to the 30-06 Ackley Improved, only the light, 125-gr. bullet utilizes BL-C (2). In cartridges larger than .30 caliber, BL-C(2) shows up in the 8mm-06 and 35 Remington with 200-gr. bullets, and in the 358 Winchester with 200-gr. and 225-gr. bullets, the latter being the largest cartridge in the Sierra manual that includes a BL-C(2) listing.

BL-C(2) first appears in the current Sierra manual with the 219 Donaldson Wasp; while starting there and running up to the 358 Win covers a lot of territory, in reality BL-C(2) skips over many cartridges. Its comfy home seems to be on the non-magnum .22s.

IMR 1185

As a bit of powder trivia, one powder that didn’t long survive, compared to BL-C (2), is IMR 1185. DuPont introduced it in 1926 for the government to utilize in the .30-06 M1 cartridge (again, that’s “M1 cartridge,” not the M1 Garand rifle) loaded with the 172-gr. boat tail bullet, and discontinued it in 1938. DuPont never offered it in canister lots for the commercial market, but some IMR 1185 found its way into civilian hands, perhaps as surplus, but maybe by some other route. I have found no published load data in any major component manufacturer’s reloading manual for IMR 1185 going back to mid-20th Century, which would seem to indicate that no one bought it in quantity, as Bruce Hodgdon did BL-C, for resale. Powder performance varied from lot to lot, which is normal for government-issue powders, so handloaders had little to go on when they did acquire IMR 1185. Even so, mention of it occasionally shows up in old gun magazines dealing with handloading, but seems to have faded away completely by 1960.

Today BL-C(2) remains a popular powder, although packaging has changed.

Why such a short life span for IMR 1185? The interwar years were a time of continued, accelerated development of newer and better US weapons based on lessons learned in the Great War of 1914-1918 and made imperative by the alarming saber-rattling in Europe. Perhaps IMR 1185 was short-lived because further development by DuPont found that IMR 4895 was better-suited to the heavy 172-gr. boat tail bullet M1 cartridge, which was intended to extend the effective range of machine guns. Or perhaps more likely, because M2 Ball with its 150-gr. bullet replaced the M1 cartridge as the standard .30 caliber cartridge for all so-chambered arms, and IMR 1185 just didn’t perform as well as IMR 4895 in M2 Ball.

Regardless, IMR 1185 is not alone in the smokeless powder graveyard. It is in the company of once-popular powders like Hi Vel-2, Ball-F and a platoon of others that have fallen by the wayside as smokeless powders improve and evolve.