by Art Merrill | Contributing Editor

The 6.5×50 is overshadowed in popularity by the 6.5×55 Swede, 6.5 Creedmoor and 6.5 Grendel (L-R).

During WWII the Japanese fielded two different front-line battle rifles firing two different cartridges. The Arisaka Type 99 rifle and its 7.7x58mm cartridge went into service in 1939, but it never replaced the Type 38 Arisaka firing the semi-rimmed 6.5x50mm cartridge. This latter cartridge is our subject here.

Like its European counterparts, the semi-rimmed 6.5×50 is Japan’s late-nineteenth century smokeless military cartridge, adopted in 1897. As such it started with a comparatively heavy round nose bullet of 162 grains launched at a relatively sedate 2,300fps. Again emulating the Europeans, bullet weight later dropped to 139 grains and velocity stepped up to 2,500fps. Alternate names for the cartridge include 6.5x50SRmm Arisaka, 6.5 Arisaka, 6.5x50mm Japanese, 6.5 Jap and .256 Jap.

Cheap sporters

Compared to other military cartridges used widely during WWII, the Japanese Arisaka cartridges were not as popular with post-war American sportsmen. That’s almost certainly not due to any lacking on either the Japanese cartridge’s performance: the Japanese 7.7 is pretty much identical to the 303 British in that regard, and the 6.5×50 is suitable for game up to deer and black bear size with the right bullets.

Rather, we can blame the Japanese Arisaka battle rifles themselves for sportsmen’s sniffs of disdain. After WWII there was a big US market in converting military bolt action rifles into hunting rifles, often rechambering or reboring them to common American calibers. The Japanese Type 38 Arisaka rifle chambering the 6.5mm cartridge earned a reputation for being extremely strong, able to withstand quite high cartridge pressures, but gunsmiths found it and the Type 99 difficult, expensive, and often completely unsuitable by design to convert into excellent hunting rifles. The Arisakas fell by the wayside and took their cartridges with them as American hunters warmed to Mausers and Springfields.

Uncomplicated reloading

Still, if you happen across a bargain on a Type 38, or perhaps inherited one, it’s an easy opportunity to form your own experience-based opinions. The mechanics of reloading the 6.5×50 Arisaka is straightforward and uncomplicated. If you haven’t loaded semi-rimmed cartridges yet, no sweat, nothing is different. “Semi-rimmed” (hence the “SR” in 6.5x50SRmm) just means the case rim is slightly wider than the case body, but the 6.5×50 cartridge still headspaces on the shoulder, like rimless designs such as the .308 Winchester.

Two-die sets are readily available from the usual makers at their usual respective price points, with Lee Pacesetter starting around $32 and Redding Premium sets topping out the choices at around $140. We can extend brass life and perhaps enjoy a bit more accuracy by neck sizing cases after firing. Shell holders for the 6.5×50 are the Redding #32, Lee #10, RCBS #15 and Hornady #34.

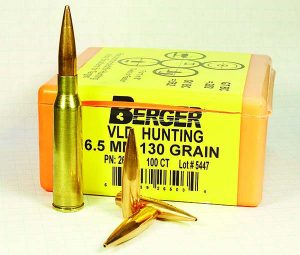

Berger 130-gr. VLD Hunting bullets reached high-end velocities without pressure signs in a Type 38 rifle.

Serbian ammo maker Prvi Partizan, as well as Norma, makes unprimed 6.5×50 brass. Various sources report a cartridge bullet diameter of .261”, .262” and .264”, with the overwhelming majority listing the latter. Smith’s Book of the Rifle, among other sources, indicates Type 38 rifle bore and groove diameter is .256” and .262”, respectively. This makes common 6.5mm/.264” bullets the choice for handloading. Powders are in the 308 Win class, such as IMR 4064, and cases utilize large size rifle primers. See? All pretty standard stuff.

The quality of Type 38 rifles, unsurprisingly, declined as WWII went against the Japanese, and some shooters report chambers can be a bit roomy to the point of bulging brass somewhat. If chamber length is excessive you may see flattened primers and/or possibly a bright ring of lighter colored brass just in front of the case web, an indication of incipient case head separation. It’s always wise to have a vintage rifle’s headspace checked first.

Starting bullets close to the rifling is well-known to improve accuracy. Throats in military rifles, however, are typically generous, and though maximum cartridge overall length (COAL) is given as 2.855” to 2.940”, it may pay to experiment with accuracy by seating bullets as far out as possible while still allowing cartridges to feed through the Type 38’s magazine. Another approach is to use round nose (RN) bullets which have very short ogives, placing the start of the bearing surface close to the nose and, therefore, the rifling. The tradeoff here is that that RN 6.5mm bullets run 155 to 160 grains, which may or may not stabilize well in later Type 38s with 1:9 twist (see below). A few excellent hunting bullets worth the experiment include Norma’s 156-gr. Oryx, which Norma claims expands at even low velocities, Lapua’s 155-gr. SP which is pretty much a RN, and Hornady’s 160-gr. Interlock.

Note also that groove depth in the Type 38s is inconsistent rifle to rifle, probably more so in the later ones; we may need to go to cast lead bullets if jacketed bullets don’t show decent accuracy. Lyman’s reloading manual, of course, is the source for cast bullet load data.

Load up

Sierra’s fifth edition reloading manual lists loads with their bullets from 85-gr. to 140-gr. While the earlier Type 38s had rifling twist rates of 1:7.9, those of late manufacture apparently had twists of 1:9. Compare that to the 1:7.9” twist of the very accurate Swedish M96 Mauser firing a 156-gr. bullet and, later, a 139-gr. bullet, and one has to wonder why the Japanese bothered making a manufacturing change mid-war to slow the twist for the lighter bullet.

(L-R) Rimmed 30-30, rimless 260 Rem, semi-rimmed 6.5×50. The rim of semi-rimless cases extends only slightly wider than the case body; the 6.5×50 headspaces on the shoulder.

While heavy (longer) bullets with higher SDs and BCs are desirable for their deep penetration and resistance to the wind, the Type 38 rifle is not a long range affair nor is the 6.5×50 eminently suitable for BIG big game. That 1:9 twist in later Type 38s is another reason to not start with the heaviest 6.5mm bullets in these rifles (note Sierra data does not include 160-gr. bullets)—they may not stabilize and there’s no sense in starting a new handloading project with disappointment. Finally, the heavier bullets must necessarily protrude further into the case, taking up powder space that we could otherwise convert into velocity or, depending upon powder selection, greater precision (accuracy).

Marginal twist rate aside, maximum loads with 160-gr. bullets in the 6.5×50 produce muzzle velocities down in the 2,000-2,400fps range; many of these heavyweights are designed to start at higher velocity in magnum cartridges to expand properly in big game animals, so the 6.5×50 may not be suited for them except perhaps at the very shortest hunting ranges or for target shooting.

At the other end of the spectrum, the 6.5×50 will push jacketed 85gr bullets nearly to 3,000fps; several data manuals show 2,900fps with maximum charges of IMR 4320. Bullets of 120 to 140 grains perhaps take best advantage of the 6.5×50, especially in the Type 38 rifle, given rifling twist and case capacity. Hornady data show their 129-gr. SP max loads at 2,700fps; Sierra has both hunting and a MatchKing bullet in that weight at the same max velocity. Stepping up to 140-gr. bullets lowers muzzle velocities to around the 2,400-2,600fps range.

Old vs new

Military chambers tend to be lengthy and need bullets seated well out. L-R, 130-gr. VLD handload, original 130-gr. military load.

For the first outing with a recently acquired Type 38 Arisaka rifle, I chose to load 130-gr. Berger VLD Hunting bullets and H4831SC for no other reason than to use up remnants of each. With no load data available for that combination (the Berger manual doesn’t include the 6.5×50) I cross referenced several manuals listing 140-gr. bullets with Hornady’s 6.5×50 data for their 129-gr. bullet in that cartridge and settled on a starting load of 37 grsins H4831SC. I loaded additional cartridges of 38, 39 and 40 grains with Winchester primers and fired all over a chronograph. Velocities measured 2,200fps with the lightest charge and 2,500fps with the heaviest. Combined with a careful examination of cases for overpressure signs, the chronograph offers the confidence of knowing I can safely work within this range of powder charges with these bullets and primers while I work up an accuracy load.

One of the benefits of being a handloader is that we can take advantage of a screamin’ good deal on a gun from a seller who thinks finding the ammo is too complicated or expensive. The Type 38 Arisaka and its 6.5mm cartridge is a perfect example.

Strength and conversions

The Japanese fielded the 6.5×50 Type 38 rifle for nearly 50 years. (Image courtesy Museum of New Zealand)

Most shooters have heard comments about the strength of the Arisaka Type 38 and Type 99 actions. These come from an older generation of veterans and sportsmen and the days when milsurp Arisakas were plentiful and cheap. Frank de Haas describes rechambering a Type 99 to 30-06, filling a case with fast powder and firing the rifle remotely. The extractor and magazine parts went flying and the barrel came partially out of the receiver, while the bolt body froze solidly within the somewhat bulged but intact receiver. The bolt handle broke off when attempting to open the bolt. Unscrewing the barrel from the receiver showed the brass cartridge case head had welded to the bolt face. De Haas reported that the chamber had not expanded at all and that the barrel was later used on another rifle.

On the sane side, a cottage industry of 1950s gunsmiths converted milsurp Type 38s to shoot the 257 Roberts or that case (the 7×57 Mauser) mounted with a 6.5mm bullet. Army Ordnance in Tokyo, Japan converted a number of Type 99s to shoot M2 Ball 30-06 for issue to South Korean troops at the time of the Korean conflict. If any of these survive in ROK armories, perhaps they’ll be included with the M1 Garands that we loaned South Korea and which shooters hope the US government will finally see repatriated in the near future.