by Art Merrill | Contributing Editor

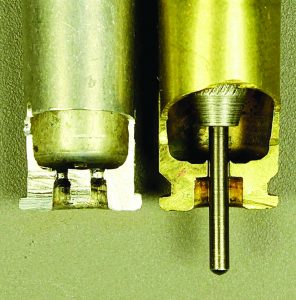

Left, the anvil for Berdan primers is built-in at the center of the case head between the two flash holes. Boxer case on the right has a single flash hole. You can see why attempting to deprime Berdan cases with conventional dies will break the decapping pin.

There must be some kind of evolutionary advantage in demanding absolutes because it seems that everyone wants them. Absolutes define the edges of a comfort zone within which we confidently expect predetermined events to not vary. Absolutes allow us to accurately predict the future, and maybe that’s what we’re really after. Many questions asked by readers and students explore the boundaries of our particular absolutes in handloading; very often the answer is a less-than-satisfying, “That depends,” because absolutes themselves are constrained by predetermined conditions and modified by caveats. Two of the most common questions asked by new handloaders are about primers.

How long will primers last?

The discovery and isolation of fulminates at the cusp of the 19th century made possible John Forsyth’s invention of the percussion cap, which incorporated fulminate of mercury. The percussion cap eventually completely eclipsed the flintlock, and when self-contained cartridges made caplocks obsolete, fulminate of mercury found a new home in cartridge primers. While other materials began replacing the corrosive fulminate around 1920, it still dominated until the 1940s.

In addition to fulminate of mercury inducing bore corrosion unless cleaning quickly followed shooting, these primers (and percussion caps) had a comparatively short shelf life, some as little as a year or so. At the outbreak of WWII, the US Ordnance Department began requiring significantly longer primer shelf life from manufacturers. These newer primers are still manufactured today and, lacking fulminate of mercury, will last almost indefinitely when kept in conditions of low humidity.

That low humidity caveat is the determining factor. Purchased new and stored in steel milsurp ammo cans with good gaskets, I have a reasonable expectation that my primers will work as advertised for the rest of my life. The same storage caveat applies to loaded ammo. In fact, ammo I loaded for a big game rifle in 1998 (according to my notes on the box) and stored in a gasketed steel ammo can still shot MOA in the same rifle last season. It helps that the air inside the can is arid Arizona air; sealing new primers in a gasketed ammo can on a rainy Florida afternoon is a different matter, calling for the inclusion of some kind of desiccant to absorb the humidity from the damp air sealed into the can with the primers when closing the lid.

Spent Boxer primer cup (L) and its anvil (center). Anvil is visible in the new primer on the right.

You will note that some primers have a colored lacquer-like material atop the anvil that appears to seal the contents of the primer cup: a correct assumption. You’ve also noted that loaded milsurp ammo appears to have a colored lacquer seal around the primer, and if you’ve pulled bullets from milsurp ammo you may have seen a similar material sealing the bullet, as well. These sealants protect against moisture intruding into the case (and sometimes also identify special purpose cartridges) and degrading primer and powder performance and longevity. The combination of long shelf-life primer material, sealing individual cartridges and then sealing cartridges in airtight containers such as “spam cans” and gasketed ammo cans works so well that we are shooting WWII vintage ammo today, 75 years later.

We often inherit primers along with other reloading goodies, or perhaps buy them secondhand. We have no way of knowing for sure how their previous owner stored them, and so we can be less assured of their longevity regardless of how we subsequently store them. I relegate such primers to classroom training, or I earmark them for “noncritical” loads – that is, for fireforming, plinking loads or other cartridges on which load testing, match scores or the outcome of a hunt don’t depend.

Of course, the major indicator of primers gone south is the misfire or hangfire. While disconcerting, on the positive side either failure will clearly reveal whether you flinch. To preclude future aggravation, this is a time to deep-six that bunch of primers or break down for components that milsurp ammo, accept the loss of whatever small investment you have in them, and move on.

So, the answer to, “How long will primers last?” appears to be, “If made in the US after WWII and stored in low-humidity conditions, longer than you.”

Why can’t we reload Berdan primed cases?

Red sealant is visible surrounding the primer in this milsurp M2 Ball cartridge.

Actually, we CAN reload Berdan primer type cases, but it requires the use of tools specifically for dealing with Berdan primers. Resources for Berdan primers and tools in the US are limited, and the cost of Berdan primers is, unsurprisingly, higher than that of Boxer primers. Add the fact that 99.999 percent of factory ammo in the US is Boxer primed, and you can see why Berdan strikes out with handloaders here.

Oddly, though Hiram Berdan patented his primer in the US in 1866 and Edward Boxer invented his Boxer primer in England that same year, the Boxer is now “our” primer and the Berdan belongs to Europe (or, at least to their militaries). In fact, Berdan primers are so not-used here that US ammo makers utilize them to deliberately discourage reloading aluminum and polymer cases, which don’t have the strength for safe multiple firings.

Primers work by the blow of a firing pin crushing the percussion-sensitive chemical mixture between the primer cup and an anvil. Unlike the Boxer primer, the Berdan has no anvil, the Berdan’s anvil being a part of the case head. This difference in primer configuration permits Boxer primer cases to have a single flash hole in the center of the case head to introduce the primer ignition into the case; when reloading we pass a decapping pin through that central flash hole to punch out that expended primer with its integral anvil.

Berdan primed cases necessarily have two flash holes with the integral anvil situated between them in the center of the case. If you run a Berdan style case into your decapping/resizing die, it will bend or break the decapping pin where the pin contacts the (essentially) back side of the anvil in the center of the case.

Berdan primers also appear almost universally in steel case ammo. Initially a wartime exigency to divert copper (the major ingredient in brass) to other purposes, steel cases are in commercial production today because steel is cheaper than brass. It is the combination of Berdan and steel that makes us treat these cases as “unreloadable.” It is possible to resize steel cases and to crimp new bullets into them, but steel is not as malleable as brass and so you’d probably notice they need a bit more lube and oomph to work them through dies. Reaming or swaging any primer pocket crimp would be harder on both tool and handloader. Also note that steel cases require some kind of coating (historically lacquer, though today some steel case ammo features a polymer coat) to protect against rapid corrosion and help assure reliable feeding and extraction in auto and semiauto firearms. Any loss of that coat through repeated reloading or even excessive handling quickly invites corrosion.

All that said, there is a way to convert Berdan style cases to accept Boxer primers. But why should we bother? Certainly you can come up with a few good reasons, but let’s save that subject for another discussion when we examine that Berdan-to-Boxer conversion in a future detailed how-to.