By Art Merrill | Contributing Editor

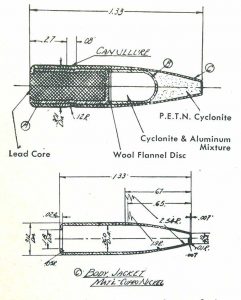

Hazardous to even handle, the Japanese used explosive machine gun ammo in rifles at war’s end in the 7.7 expander bullet. Illustration from American Rifleman magazine, September 1951; origin unknown.

The pursuit of a better projectile has been a matter of course since the introduction of firearms, and every few years manufacturers seem to come up with something better. “Better” is relative and varies with the task we set for it, but a better bullet still needs the fundamental attributes of flying true and adequately performing its given task when it arrives on-target. For competition we emphasize the former and essentially care nothing about a bullet’s terminal performance; hence the caution from makers like Sierra and Berger to never use their superb target bullets on game animals.

When intended to stop humans and other animals, however, “better” bullets have an emphasis on terminal performance equal to or greater than that on a bullet’s precision flight. These dual needs—precision flight and terminal performance—are tackled as separate problems in aerodynamics and metals engineering wedded together. As knowledge in those fields increases, we get better and better self-defense and hunting bullets that fly straighter and expand reliably across a wider range of velocities.

A box of Exploder brand ammunition that recently passed through my hands gives pause here at year’s end to look backward and consider the path we followed to get where we are with today’s excellent bullets. Let’s start at the heady days when it seemed newfangled “high velocity” cartridges and expanding jacketed bullets could do almost anything.

Exaggerate

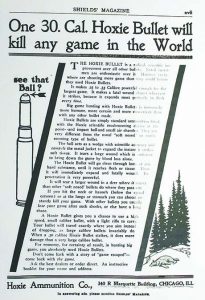

The Hoxie bullet was available from about 1906 to the 1920s. In essence the Hoxie was a kind of mechanical/pneumatic bullet in that it had moving parts and supposedly worked on the principle of compressing air.

The Hoxie featured a round metal ball in the tip of a hollowpoint rifle bullet. The idea was that, upon striking its target, the ball pushed back into the hollowpoint cavity, compressing the air behind the ball that then forced the walls of the hollowpoint tip to expand outward. Hoxie advertising of the day claimed miraculous instant kills even with gut shots from this, “radical, scientific improvement over all other bullets” and that it would “travel exactly where you aim instead of dropping, as large caliber bullets invariably do.”

While the Hoxie is long gone, the ball-in-a-hollowpoint concept is still with us today, sans exaggerated claims, such as in Glaser’s Pow’RBall ammunition (most polymer tips on rifle bullets are aids to aerodynamics, not necessarily expansion).

Explode and devastate—sort of

Birmingham, LTD of Atlanta, GA, made Exploder ammo in the 1970s.

The 1970s-era Exploder ammunition mentioned earlier is similar in the concept of aided expansion, but different in method. In place of an expander ball, the hollowpoint of the Exploder holds a few grains of Pyrodex capped with a common cartridge primer with its anvil facing the charge and the bullet tip sealed with yellow lacquer.In theory, when the primer in the bullet nose strikes a target, it detonates, igniting the Pyrodex which forces explosive expansion of the hollowpoint. In reality, soft targets appropriate for expanding bullets are too soft to reliably detonate the primer. The manufacturer, Bingham LTD, produced a second offering, a “Devastator” bullet with an explosive lead azide and aluminum charge in the nose that appears to have worked a little better. Unfortunately!

The Exploder used a lacquer-coated, reversed primer to detonate Pyrodex in the bullet’s hollowpoint.

John Hinckley Jr. used .22 rimfire Devastator cartridges in his attempt to assassinate President Ronald Reagan in 1981. Of the six shots Hinckley fired in less than two seconds, two struck no one, a ricochet off the president’s limo struck Reagan, and three struck others. The only Devastator bullet that actually “exploded” was the one that struck Press Secretary Jim Brady in the head. That incident and paralyzing injury to Brady led Handgun Control, Inc., to linkup with Jim and Sarah Brady and to subsequently rename itself several times while expanding its anti-civil rights mission to become, for a time, the Second Amendment’s most vehement threat.

Shoot airplanes, not people?

As you’ve noted, however, these are not truly exploding bullets. Are there any bullets that actually explode like a cannon shell?

Glaser Pow’RBall ammo uses a polymer ball as an expansion aid.

The St. Petersburg Declaration of 1868 prohibited military exploding or inflammable projectiles weighing less than 400 grams (about 1 pound, the weight of the smallest cannon shell then), the rationale apparently being that shooting someone with an exploding bullet is inhumane, while blowing them up is not. The signatory nations fielded exploding and incendiary small arms bullets anyway as anti-materiel, rather than anti-personnel projectiles, the circumventing legalese being that such bullets are intended to destroy a machine, not the person within it.

In WWII, for example, the Russians utilized a 7.62x54R “ShKas” cartridge intended for aircraft machine guns, the bullet of which contained an explosive charge of tetryl and an incendiary. Due to hard primers and internal construction these rounds tended to misfire in rifles, so primers and bullets had identifying red lacquer and ammo boxes carried a red propeller mark to ID the special cartridge.

The Japanese fielded 7.7 and 7.92 machine gun rounds tipped with PETN and RDX explosives during WWII. According to the January 1945 US War Department Intelligence Bulletin, “Three different types of explosive and incendiary small-arms ammunition have been captured from the Japanese in the Southwest Pacific area. Because of the unusual characteristics of this ammunition, serious injuries sometimes have resulted when soldiers have tampered with it out of ignorance or curiosity…These bullets are not fuzed, but explode or ignite when the copper jacket is ruptured on impact with the target. The explosive bullet may be recognized by its flat nose, but the incendiary has the pointed nose of an ordinary bullet. The explosive bullet is capable of blowing a 3-inch hole in a sheet of aircraft Duralumin.”

Hoxie advertising from 1907 claimed instant kills on gut shot game. Ad from Shields’ Magazine, July 1907

The Bulletin also notes. “Apparently first manufactured for use in Japanese aircraft or antiaircraft weapons, some of this ammunition has been found loaded in five round clips, presumably for use in infantry weapons.”

An editor’s post-war vignette in the September 1951 American Rifleman warned handloaders against tinkering with or attempting to pull these explosive bullets from cartridges because they were so sensitive. That caution serves us well today.

Don’t try this at home

As handloaders gain expertise it’s inevitable that we begin to ponder possibilities beyond the ordinary. Exploring an idea is the basis of invention, but experimenting at the fringes of handloading is a dicey matter. Do note that attempting to manufacture an exploding bullet at home apparently crosses the fringes of legality, as well. A June 2013 ATF newsletter advises, “…bullets containing other pyrotechnic mixtures or high explosives (e.g. exploding bullets)…do not meet the definition of ammunition under 27 CFR 555.11,” and “persons acquiring such ammunition must have a license or permit unless otherwise exempt…” ATF has not responded to my questions asking about exemption and acquiring (or selling) Devastator or Exploder cartridges as curiosities.

It’s important to always keep in mind that, no matter how comfortable we become in making our own ammunition, we are dealing with materials sensitive to impact detonation (primers), insidiously toxic (lead), highly flammable (smokeless powder) and even explosive (black powder). Of course you are responsible for your own safety and free to take whatever risks you wish, but we also have an obligation to not unnecessarily endanger others—whether we are handloading or simply driving our cars, for that matter.

Have a safe and happy 2017.